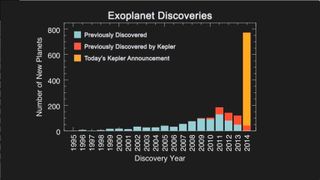

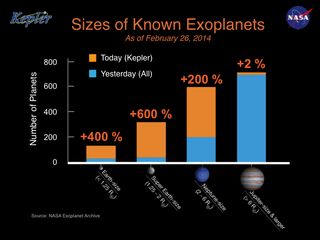

NASA's Kepler space telescope has discovered more than 700 new exoplanets, nearly doubling the current number of confirmed alien worlds.

The 715 newfound planets, which scientists announced today (Feb. 26), boost the total alien-world tally to between 1,500 and 1,800, depending on which of the five main extrasolar planet discovery catalogs is used. The Kepler mission is responsible for more than half of these finds, hauling in 961 exoplanets to date, with thousands more candidates awaiting confirmation by follow-up investigations.

"This is the largest windfall of planets — not exoplanet candidates, mind you, but actually validated exoplanets — that's ever been announced at one time," Douglas Hudgins, exoplanet exploration program scientist at NASA's Astrophysics Division in Washington, told reporters today. [Kepler's Exoplanet Bonanza Explained (Infographic)]

About 94 percent of the new alien worlds are smaller than Neptune, researchers said, further bolstering earlier Kepler observations that suggested the Milky Way galaxy abounds with rocky planets like Earth.

Most of the 715 exoplanets orbit closely to their parent stars, making them too hot to support life as we know it. But four of the worlds are less than 2.5 times the size of Earth and reside in the "habitable zone," that just-right range of distances that could allow liquid water to exist on their surfaces.

![A powerful new technique for hunting alien planets yields a major new crop of new worlds. [See how Kepler made the planet discoveries in this Space.com infographic]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/usuyLzWSuTvRamQKguY9DN-320-80.jpg)

The $600 million Kepler spacecraft launched in March 2009 to determine how frequently Earth-like planets occur around our galaxy. The observatory detects alien worlds by noticing the telltale brightness dips caused when they pass in front of, or transit, their parent stars from Kepler's perspective.

Kepler's original planet-hunting mission ended last May when the second of its four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed, robbing the spacecraft of its ultraprecise pointing ability. Still, scientists have expressed confidence that they will be able to achieve the mission's chief goals with the data Kepler gathered during its first four years in space.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Those were very productive years. Kepler has flagged more than 3,600 planet candidates to date, and mission team members expect that about 90 percent of them will end up being the real deal.

Indeed, the 715 new planets were pulled from just the first two years of Kepler observations, so more big planet-confirmation hauls could be coming as researchers work their way through the rest of the mission's huge database.

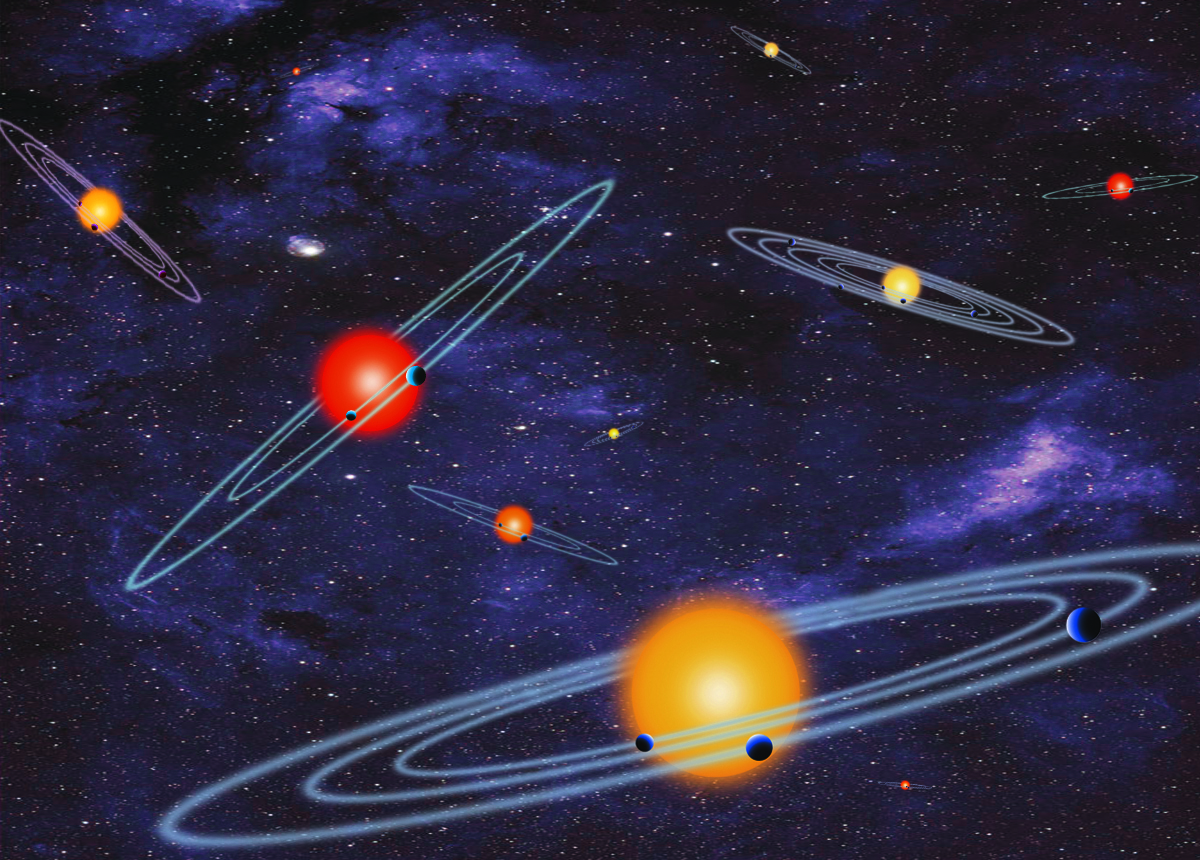

All of the 715 newfound alien planets reside in multiplanet systems, just like Earth. Taken together, the new planets orbit a total of 305 stars, researchers said. And these systems are generally reminiscent of the inner regions of our own solar system, where planets travel around the sun in circular orbits that are more or less in the same plane, they added.

"These results establish that planetary systems with mulitple planets around one star, like our own solar system, are in fact common," Hudgins said.

Scientists validated the newly discovered worlds using a powerful and sophisticated new method called "verification by multiplicity," which works partly on the logic of probability.

During its original mission, Kepler stared continuously at more than 150,000 stars, finding planet candidates around several thousand of them. If these candidates were distributed randomly, just a few would reside in multiplanet systems. But Kepler has found hundreds of such systems, a fact that helped scientists identify the 715 bona fide new planets.

"Multiplicity is a powerful technique for wholesale validation that will be used again in the future," said Jason Rowe of the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, Calif.

The method should help researchers confirm hundreds more Kepler candidates down the road, Rowe and others said. A higher percentage of these future finds should be in the habitable zone, they added, since it takes longer for the spacecraft to detect more distantly orbiting exoplanets than ones that zip around their star in a matter of days or weeks (and researchers haven't analyzed the last two years of Kepler data using the multiplicity technique).

The studies that detail the discovery of the 715 alien worlds will be published March 10 in The Astrophyiscal Journal.

The five main exoplanet-discovery databases, and their current tallies (with the new Kepler finds included), are: the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia (1,790); the Exoplanets Catalog, run by the Planetary Habitability Laboratory at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo (1,790); the NASA Exoplanet Archive (1,749); the Exoplanet Orbit Database (1,490); and the Open Exoplanet Catalog (1,714).

The different numbers reported by the databases reflect the uncertainties inherent in exoplanet detection and confirmation.

While Kepler's original mission operations have ended, the spacecraft may not be done hunting for alien planets. Team members have proposed a new mission for Kepler called K2, which would allow the observatory to search for a variety of celestial objects and phenomena, including exoplanets, supernova explosions and comets and asteroids in our own solar system.

NASA is expected to make a final decision about the K2 mission proposal by this summer, officials have said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.