At the dawn of the atomic age, the community of Oak Ridge, Tenn., rose up around the secret work taking place there in support of the war effort. At the heart of those efforts were thousands of women from across the country who did their part to help secure the United States while maintaining a public silence.

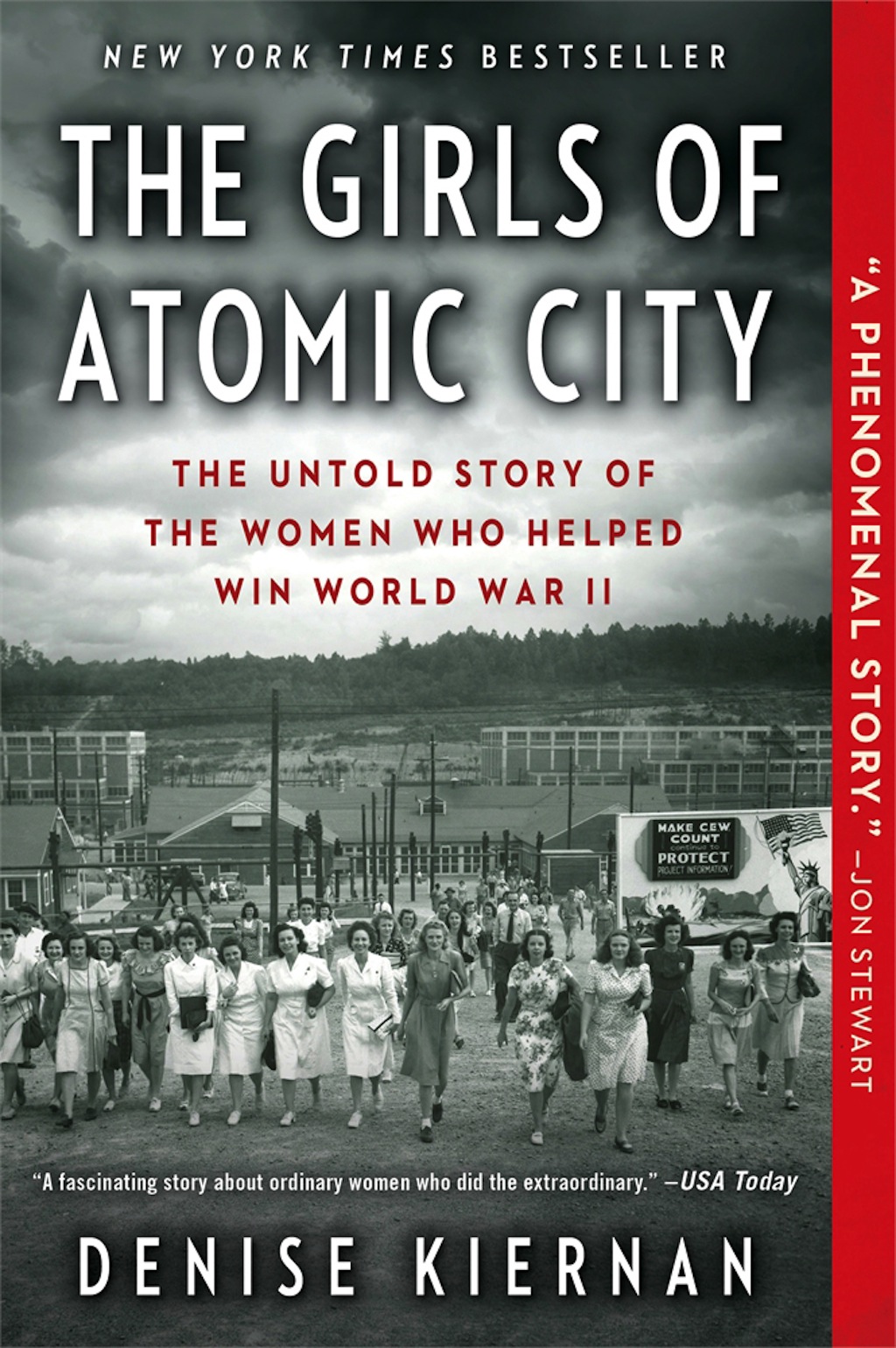

Now, more than half a century later, author and journalist Denise Kiernan is telling their story in the New York Times bestseller "The Girls of Atomic City" (2014 paperback, Touchstone, Simon & Schuster, Inc.) Based on first-person interviews with women who served at Oak Ridge — several of them now now in their nineties — Kiernan presents an insider's account of a nearly lost chapter in U.S. history.

Kiernan's work spans two decades and includes articles in The New York Times, Ms. Magazine, The Wall street Journal and other publications. Prior to "The Girls of Atomic City," she had achieved broad recognition for the history titles" Signing Their Lives Away," "Signing Their Rights Away" and "Stuff Every American Should Know." Scroll down to read an excerpt of "The Girls of Atomic City" by Denise Kiernan:

Chapter 1

Southbound trains pierced the early morning humidity. The iron and steel of progress cut through the waking landscape.

Celia sat in her berth, the delicate folds of her brand-new dress draping over her knees as she gazed out the window of the train. Southbound. That much she knew, and that she had a sleeping berth because it was going to take a while to get to her destination. Towns and stations simmering in the August heat rippled past her view. Buildings and farms bubbled up above the horizon as the train sped by. Still, nothing she saw through the streaked glass answered the most pressing question in her mind: Where was she going?

Already many hours long, Celia's trip felt more endless because her final stop remained a mystery. She had no way to measure the distance left to travel or to let her subconscious noodle over what portion of the trip had already elapsed. There was only the expanding landscape and the company of a small group of women, previously unknown to her, but with whom she was now sharing this secrecy-soaked adventure. Celia had quite willingly embarked on a journey without first obtaining much tangible information. So she sat, waiting to arrive at the unknown.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A wavy-haired 24-year-old, Celia was always up for a change of scenery, and this trip was not her first. Her hair was a deep brown, not quite as black as the coal ash that coated life in the Pennsylvania town that she had left behind: Shenandoah. It was a town about 100 miles and roughly the equivalent in light-years from Philadelphia,and which writer George Ross Leighton referred to as "a memorial to the age of rampant industry." He described her "once-prosperous" hometown as one that was, in many ways, reminiscent of so many other American towns: past its prime, fighting to survive, and abandoned by the business that had spawned its heyday, a business that kept the lion's share of profits far from the reach of the rock shredded,blackened hands that had built it. It was already a region in decline, even back in 1939. But that mining town had given Polish families like hers — and Czechs, Russians, Slovaks — work. Sometimes it was steady, most times not, but it was a chance at a decent living.

Land of anthracite! Celia's hometown was like many mining towns in the east, its lifeblood linked to the precious rock buried down deep in the surrounding hills and valleys; a high-carbon, low-impurity, more lustrous incarnation of mineral coal. Locked in the bonds that held it together was energy itself. It could be released in dreamy blue flame and bestow its power on its liberators. But soon the allure and sheen of coal had given way to grime and neglect, much as the banking room of the Shenandoah Trust, a victim of the Great Depression that was still fresh in folks'minds, had given way to Stief's Cut Rate Drug and Quick Lunch. Rather than thriving, the town was choking. Rusted smokestacks punctuated the now-polluted horizon, redbrick edifices had surrendered their vibrancy to the soot of an overworked earth, all dingy reminders of an industry that once ran rampant and now hobbled on its last legs.

That was behind her now. Every passing moment separated Celia from what could have been an ash-covered existence as the wife of another miner. She had never wanted that future but only recently realized that it was not carved in stone. As for her new employment and soon-to-be home, “secret” was the operative word. It was repeated frequently, and rendered the most innocuous of questions audaciously nosy. When Celia had asked the obvious—Where am I going? What will I be doing?—the answer was that she was not allowed to know any more than she had already been told. She would be given only the information that she needed to get where she was going. Asking questions was frowned upon.

She had gotten a taste of this “don’t ask” world of work during the short time she had spent working as a secretary for the Project in New York City. Secrets were secret for a reason. She had to believe that. If there was a need for her to know something critical, she would be told when the time was right. Whatever “it” was, it must have been very important. That said, hopping a train with her one, simple suitcase in hand had felt more than a little odd. Would she know her stop? Would something jump out at her from the landscape, some detail of its appearance crying out to her, “Yes, Celia Szapka! This is it!” Then again, she had never ventured south and she was now southbound. That much she knew.

Everything will be taken care of . . .

Celia had chosen to trust her boss, and so far what little he told her had proven true. The limo had picked her up the morning before from her sister’s home in Paterson, New Jersey. She sat alone in the car and the driver made no other stops as the car motored south through the industrial heart of the Garden State before arriving at the train station in Newark. There she boarded the train, situated her scant belongings in her prearranged berth, and waited to depart. Once at the station, she had been joined by other young women, most seeming to be about her age, and none of them any more informed than she was. Celia was somewhat relieved to know that she was not the only one being kept in the dark. She and all the other young (and she assumed single) women sitting around her were heading in the same direction. They were All in the Same Boat.

Neither Celia nor any of the other girls sitting on the train would complain about the secrecy. Complaining was not in fashion in 1943, not with so many sacrifices being made thousands of miles away, across oceans she had never seen. So much loss of life and family. How could she or anyone else heading to a good, safe job complain? The war permeated every aspect of existence, from sugar, gas, and meat rations to scrap metal drives and the draft. Businesses across the country were abandoning the manufacturing of their usual wares — from kitchen appliances to nylons— in order to churn out everything from tires and tanks to ammunition and airplanes.

Details of battles and news of troop movements did little to shorten the excruciating lapses in time between letters arriving from abroad, or to relieve the sadness for losses suffered by friends, which were sometimes followed by a twinge of guilt-laden relief when news of the dead had spared your home yet again. Small flags of remembrance, a star for each loved one, marked the homes of those affected by the war. So many stars hung in so many windows, stitched carefully by nervous mothers, sisters, and sweethearts. No matter the town, a walk down any residential street was sure to turn up blue-star banners waving alone in living-room windows, requesting silently to passersby to pray for the safe return of the brother, father, or husband that each five-pointed fabric memorial signified. And every Blue Star Mother lived in fear that her star's color might one day change, might be rendered gold by an unwanted telegram or a knock at the door, that what once hung as a sign of support and concern would be transformed into a symbol of mourning.

Everyone’s patience and nerves were being tested, and Celia's were no exception. Certainly the Szapka family had endured their share of difficulties. Despite it all — the tight money, her father's long hours in the coal mines, the ceaseless work at home — they persevered. Complaining would not help secure the safe return of her brothers Al and Clem. It wouldn't make her father's work any more steady or do anything to clear his persistent cough, which seemed to be getting worse with each labored breath.

In summer, the mines had no work for her pa. The proud Pole, never one to take a handout no matter how tough things got, refused to go on the dole. So with little money to feed their kids, Celia's parents packed Celia and her three brothers and two sisters — when they were all at home — off to their grandmother's house in New Jersey. Memories of those summer visits to Grandma were not filled with hopscotch, swimming, or cookie-baking. Celia was put to work, cleaning and scrubbing floors. Her grandparents looked after her and her siblings, making life a little easier on her parents until the mines opened back up and it was time for the kids to go back to school. But there would be no mining work for her brothers. Her parents never wanted that for their sons. They were all gone now: Al to the Philippines and Clem off to Italy. And Ed, lovely Ed, her oldest brother and her favorite, was in the tiny town of Vernon, Texas, the only place he could get his own Catholic parish.

And this was how Celia was doing her part. She quickly learned that all the women on the train had been told that their new jobs served one purpose only: to bring a speedy and victorious end to the war. That was enough for her.

★★★

It had taken several years to break the bonds with Shenandoah and her mother. The year Celia had graduated high school, her mother sent her to New Jersey — "that's where the jobs are" — to live with her older sister in Paterson. But that was about as far as Mother wanted Celia to travel. Celia got a job making three dollars a week as a secretary and hated every minute of it. She wanted badly to attend college, but there was no money. Her parents believed her younger sister, Kathy, needed the leg up more than Celia did. At three dollars a week, Celia knew she wasn't going to be able to set money aside for college anytime soon. That prospect looked no more promising in Paterson than it had back in Shenandoah.

Then a new opportunity presented itself. Celia’s cousin told her about the civil service. There would be classes, he explained, and then a test. Jobs could be anywhere, he said. Sometimes the government sent you overseas to places like Europe. Europe. The possibility alone was enough to get Celia to class. Besides, she thought, what’s the harm in taking a test?

Sure enough, within three weeks the first offer came through: to work for a reconstruction finance company. Celia wasn't exactly sure what that was, but it didn't matter: Mother forbade it.

You're not going away. You're too young. We need you close to home ... Her mother spouted a litany of reasons why Celia should not be allowed to explore the best opportunity that had ever come her way. Celia's older sister was married. Her younger sister was going to go to college. Celia was stuck in the middle, the grip of the Keystone State unrelenting, suffocating. At her mother’s insistence, Celia declined the offer. Then another job offer arrived, this one with the State Department in Washington, DC.

This time when the letter landed in Celia's lap, Celia's recently ordained brother was home visiting from Texas. How she'd missed him. Seven years her senior, Ed had moved away when Celia was still in elementary school. She'd cried for days. Maybe you're not supposed to have favorites, but Celia didn't care. Ed was hers. Mama had always said the pair were cut from the same cloth. Ed saw Celia's eyes light up when she received the State Department letter and her face begin to fall when Mama started to protest about Washington being too far afield. Celia had gotten over not being able to go to college, she’d gotten over saying no to the last job offer, she thought she'd get over this, too.

But Father Ed wasn't standing for it. And tough-but-loving Mary Szapka was no match for a priest on a mission. The discussion was heated but short, and it was decided: Celia was going to Washington to take that job, Ed said. "And I'm taking her."

Washington had been a spectacular experience, one that had reshaped Celia's ideas about her own future. She adored living in the boardinghouse on E Street, having roommates her own age, working for the State Department. And the salary! By the time she left DC she was earning $1,440 a year! She never thought she'd ever see numbers so big on a paycheck that had her name on it, let alone at 22 years old. She shared a bedroom in a boarding house with five other girls and each day made her way down the grand sidewalks of the nation's capital to work. There, the office she shared with the other secretaries had a small balcony with its own view of the White House Rose Garden. Celia would walk out there on her breaks, and on a few lucky occasions, she and the other young women spied President Roosevelt down below, as he slowly made his way around the manicured grounds. The girls would wave excitedly. Once he even waved back. The President of the United States. Imagine that.

Those years in Washington had loosened Celia's ties to home, but her mother kept on tugging. When her boss, Ambassador Joseph Grew, wanted Celia to transfer to Australia — a big vote of confidence in Celia’s abilities—that tug turned into a yank. But Celia couldn't return home. Not anymore. She'd seen too much, done too much, earned too much. Any future in Shenandoah seemed dismal, certainly devoid of any intrigue. There had to be a better way to pacify her mother and not abandon everything she had already built for herself. She had to see about getting a job closer to home — just not at home.

New York City. When Celia's transfer came through all she knew about her job was that it was for the war effort, it was not in Shenandoah, and her mother couldn't complain that it was in Australia. She was living back in New Jersey again, but this time it was different. She was a real working woman now, joining the hordes of other Jerseyites who took the train every day across the Hudson and into Penn Station.

Celia adored Manhattan — the noise and grime and glitz and crowds. Her walk from the train to her office was filled with shops and people and a constant buzz that sustained her every step. Sometimes after work, she walked along Fifth Avenue, or strolled through Times Square. Shenandoah was again a memory.

At first glance, there was nothing particularly noteworthy about the building at 270 Broadway in New York City. Standing across from City Hall Park, it was a large office building in a sea of large office buildings cramming the twisting streets of lower Manhattan. By the time Celia boarded her southbound train in August of 1943, the 18th floor of 270 Broadway had been the home of the North Atlantic Division of the Army Corps of Engineers and the first headquarters of the Project for nearly a year.

The 270 building wasn't the only site on the island that played a role in the Project for which Celia now worked. All across Newstorage for tons of processed material from the Eldorado Mining and Refining Limited company in Canada, material that was the key to the Project. This material was not the kind of ore from Celia's corner of Pennsylvania, but another rock altogether. This ore was called Tubealloy by many in the Project, its real name no longer to be spoken aloud or written down. Tubealloy was the element upon which all the Project's hopes depended, and huge quantities of it were stowed away across New York Harbor, in the Archer Daniels Midland warehouses on nearby Staten Island.

Tubealloy was why Celia's job existed, though she knew no more about it than the average New Yorker bumping and bustling past her on the overrun train platforms. But all across the island, in anonymous buildings and offices, countless people were quietly dedicated to finding, extracting, and purifying the Tubealloy needed for the Gadget.

Celia quickly became accustomed to secrecy in her secretarial post. She signed many papers, offered her fingerprints willingly, and endured not a few lectures about the importance of never discussing anything that she did at work. She could still hear her mother's voice warning her about the dangers of contracts.

"Be sure you read everything you sign! You might sign your life away!" she said.

Celia had responded with the customary "Oh, Mom ..." But she had, nevertheless, read everything that she had signed. It all seemed natural to her somehow, as though the absence of detail implied the job’s importance.

This latest, peculiar transfer had come shortly after Celia had relocated to the Project offices in New York City. Only four months had passed when Celia’s boss, Lt. Col. Charles Vanden Bulck, called Celia into his office and asked her if she would be willing to transfer yet again. The offices were relocating, he explained, and he needed to know if she was willing to go along with them.

"Where are we going?" Celia asked.

"I can't tell you."

Celia wasn't quite sure what to make of this and pressed a bit, York City, other pieces were falling into place. The Madison Square Area Engineers Office at 261 Fifth Avenue was charged with securing materials. Research was happening in Pupin Hall at Columbia University. The Baker and Williams Warehouses offered temporary wanting to know at least what direction she was headed. If it was far, she was going to hear it from her mother.

"It all depends on how far away it's going to be," she tried to explain.

But Vanden Bulck still would not say. All he would tell her was that the move was for an important project and that the destination was top secret.

"Well then, what will I be doing?" she wondered.

Again, no real details. She wasn't quite ready to give up yet. They had to tell her something.

Didn't they?

"For how long?" she finally tried. If she were going away again, her mother would at least want to know how long she would be gone. Surely they could tell her that much.

"Probably about six months, maybe nine," was the answer.

There it was, her official offer: some kind of new job in some kind of place and probably for about six, maybe nine, months. Perfect. Her mother would love it.

"How am I going to get there?"

"We'll pick you up and you'll go by train. Everything will be taken care of."

Celia signed on.

She would explain to her mother that it was for the war, for Clem, and for Al. Mama couldn't say no to that.

My God, it was a job! A good job, a well-paying job. There were worse fates than a bit of secrecy as far as she was concerned. Other women in other cities were doing what they could, moving into the workforce in record numbers. A cover of the Saturday Evening Post in September 1943 would depict a Stars and Stripes–clad woman, marching forward, toting everything from milk, a typewriter and a compass to a watering can, telephone, and monkey wrench. Women's roles in the workforce were expanding exponentially. And with not one but two brothers fighting overseas, Celia felt something that overrode any misgivings: Purpose. Duty. If doing her part meant leaving home for some unknown, godforsaken place, then that's what she would do.

★★★

Now the tracks stretched out before the train, the distance that separated Celia from her parents was the greatest it had ever been, and was growing still. She had managed to get some sleep during the night as the rickety sway and swivel of the train rocked bodies gently to and fro. She had made some new friends on the journey. But it was past dawn now and she was getting anxious. She was wearing her new dress, the one her sister Kathy had bought for her. The dress was black and white, with a straight skirt — not too long but certainly not too short. It may not have had a designer label, but it was the fashion of the moment. A smart hat sat atop her meticulously groomed locks, and she wore the coveted I. Miller shoes that she had bought for herself near Times Square in honor of this new clandestine assignment. Wherever she was going, she wanted to look her best. "Don't hold her back," Father Ed had said to her parents. She wouldn't be here without him. She had the chance to make something of herself. She wasn't going to waste it.

Soon a slight buzz grew into a full chatter that bounced off the sleepy bodies in the train car. The gaggle of girls began whispering to each other that the train was slowing and that they were all getting off at the next stop. Celia looked out the window and soon the sign hanging above the station platform came into view: Knoxville, Tennessee.

Is this it? she wondered.

Celia gathered her bag and followed the other women as they made their way through the car, down the stairs, and onto the platform. August smacked her unceremoniously in the face, a humid stagnant "hello" greeting her as she exited the train. It was quite an exodus. It appeared to Celia as if everyone had gotten off the train.

A man approached them explaining a car was waiting to take them the rest of the way.

Everything will be taken care of ...

Celia piled into one of several vehicles parked outside the station, bursting to know their next stop. But it was early still — right around six o'clock in the morning — and the official-looking man who had come to fetch them said they were all going for breakfast.

The downtown buildings loomed high for Knoxville but not so much in Celia's eyes, accustomed as she was to the cloud-grazing rooftops of New York City. The car turned down Gay Street, one of Knoxville's main drags. The streets were starting to awaken. Deliverymen carted what rationed meats and sundries were available to the shops vying for their share, the bark of a newspaper vendor cut through the early morning hum and shuffle of workers heading off for the early shift. The town car slowed and halted at 318 North Gay Street. Celia looked up. Nestled beneath the Watauga Hotel sat the Regas Brothers Cafe.

She exited the car and entered the restaurant, a long, large, open space with soaring ceilings. Booths lined one wall and a long counter anchored the opposite side of the room, its length measured by

18 swivel stools. Six larger tables stretched between them down the middle of the room, draped in starched white tablecloths and flanked by arched, cane back chairs. Men in crisp white shirts, long ivory aprons, smocks, and narrow, black ties hurried across the polished tiled floors. Celia and the other girls sat at the counter pondering the menu.

One menu item puzzled them. Like Celia, most of the women hailed from Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey. None had heard of any such thing as "grits." At the Szapka house, it was Polish food three times a day, and that suited Celia just fine. Even when things were tight—and they almost always were—her mother put a good meal on the table. Neighbors who lacked Mary Szapka's baking prowess shared extra butter and flour in exchange for a share of the treats that popped out of the Szapka oven. And whenever Celia’s mother sent Celia to the butcher with a dollar — "Get as many potatoes as you can!" — the butcher, who had known Celia her entire life, always threw in a few extra. Potato pancakes, potato pie, potato dumplings. Potatoes.

When Celia heard the word grits, her curiosity was piqued by anything that was not of spudlike origin. A tall black waiter in a long white apron gave the girls a simple and straightforward description:

Grits were little white things made from corn. And you put butter on them. Just like potatoes. The waiter encouraged Celia to give them a try. The bowl of hot, butter-soaked hulled corn arrived and Celia put a steaming, slippery spoonful in her mouth, enjoying the first taste of her new life.

Once the women had finished their morning meal, they piled back into the limo again. The driver, pleasant enough yet wordless, drove on. Knoxville soon disappeared behind them. The landscape opened wide in every direction, framed by the low rolling hills that marked the timeless tail end of the Smokies. The rising sun of the East crept farther up the backdrop of morning sky behind them.

Though these country roads were far from where Celia had started off in Pennsylvania, their history, too, was being shaped by a burgeoning industry, one also built upon a rock — not as lustrous as anthracite, but one that held tremendous power. This rock, unknown to most Americans, was recasting not only this once-quiet slice of Appalachian farmland but the landscape of warfare forever.

Celia did the only thing that she could: wait.

While she did, other women on other trains kept pulling into the very same station, their routes like veins running down the industrial arm of the East Coast, extending from the heart of the Midwest, the precious lifeblood of a project about which the women knew nothing, all of them coursing toward a place that officially did not exist.

BUY "The Girls of Atomic City" >>>

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.