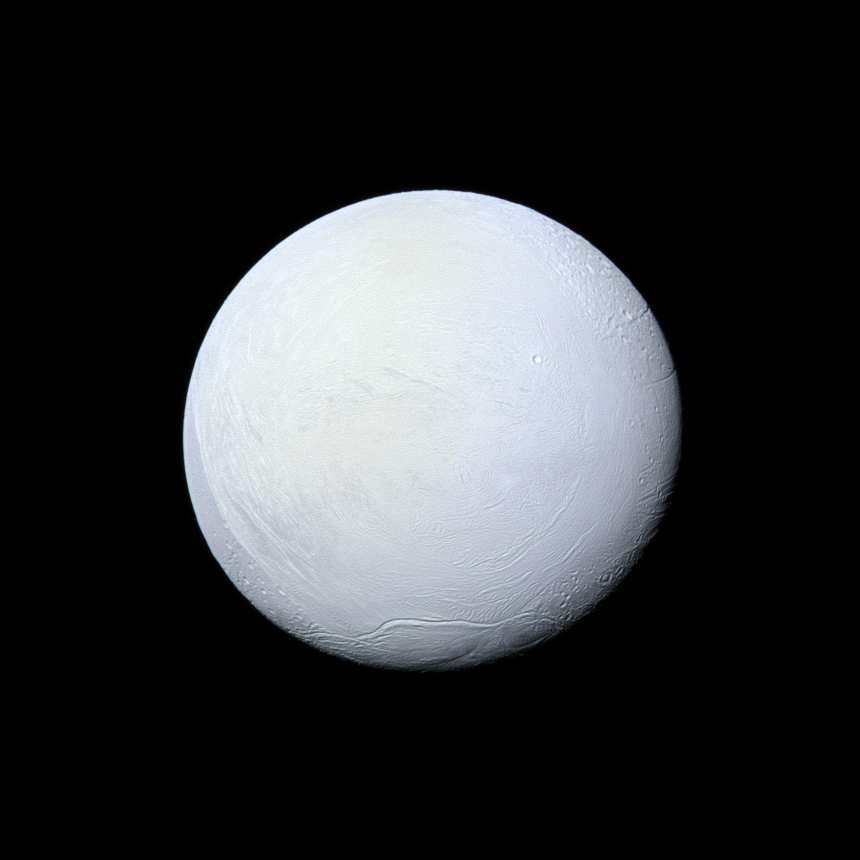

Astronomers are hoping that the existence of a subsurface ocean on Saturn's icy moon Enceladus will build momentum for life-hunting missions to the outer solar system.

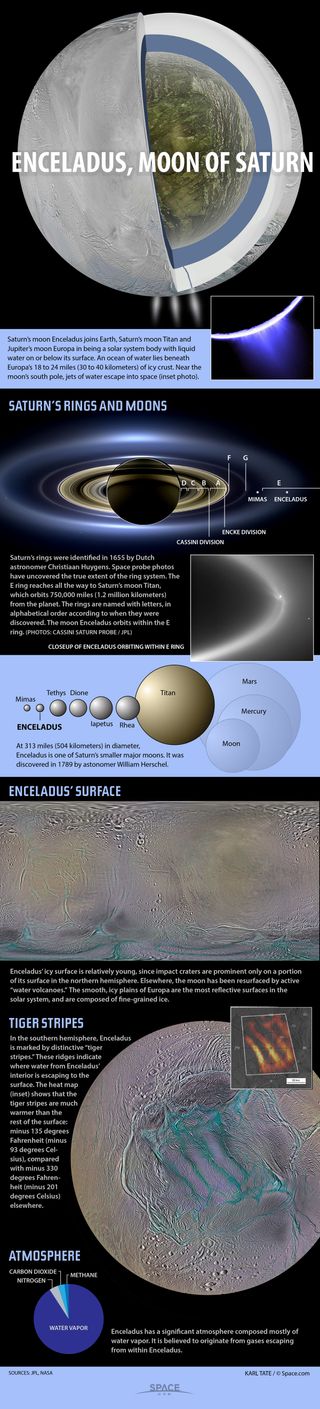

Researchers announced their discovery of the deep watery ocean on Enceladus on Thursday (April 3) in the journal Science, confirming suspicions held by many scientists since 2005, when NASA's Cassini spacecraft spied geysers of ice and water vapor erupting from Enceladus' south pole.

The discovery vaults Enceladus into the top tier of life-hosting candidates along with Europa, an ice-sheathed moon of Jupiter that also hosts a subterranean ocean. Both frigid satellites bear much closer investigation, researchers say. [6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System]

"I don't know which of the two is going to be more likely to have life. It might be both; it could be neither," study co-author Jonathan Lunine of Cornell University told reporters yesterday (April 2). "I think what this discovery tells us is that we just need to be more aggressive in getting the next generation of spacecraft both to Europa and to the Saturn system once the Cassini mission is over."

Cassini arrived in orbit around Saturn in 2004 and is currently scheduled to go out in a blaze of glory in September 2017, when it will dive headlong into the giant planet's thick atmosphere.

Enceladus' geysers blast material hundreds of miles into space, offering a way to sample the moon's subsurface ocean from afar. (Researchers think the ocean is feeding the geysers, though they can't be sure of this at the moment.)

Cassini has already done some of this work with its mass spectrometer, detecting salts and organic compounds — the carbon-based building blocks of life as we know it — in Enceladus' plumes during flybys of the moon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But Cassini's mass spectrometer can detect only relatively light organics. A follow-up mission to Enceladus should sport a more advanced and more sensitive version of this instrument that could spot a wider range of organics, Lunine said.

"You could actually do this by making flybys of Enceladus, the way that Cassini does now," he said. "I think you could learn quite a bit about the organic inventory in the plume by flying this device."

Interestingly, astronomers announced in December that they had discovered plumes of water vapor erupting from Europa's south polar region as well. So that moon's ocean could be sampled during flybys, too — perhaps by a mission called the Europa Clipper.

NASA is developing the Europa Clipper as a concept mission at the moment. Recent estimates have pegged the mission's cost at around $2 billion. That's pretty steep in these tough economic times, so a scaled-down version might have the best chance of getting it off the ground, NASA officials have said.

Enceladus and Europa aren't the only icy moons that harbor subsurface oceans; Jupiter's enormous moon Ganymede also has one, for example. But Ganymede's appears to be sandwiched between layers of ice, while the seas of Enceladus and Europa are in contact with rocky seafloors, making possible all sorts of interesting chemical reactions, researchers say.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.