Lyrid Meteor Shower Peaks Tonight: How To Watch Live

The Lyrid meteor shower peaks tonight (April 21) and if Mother Nature spoils your "shooting stars" display with bad weather, you can watch the celestial light show live online with two webcasts.

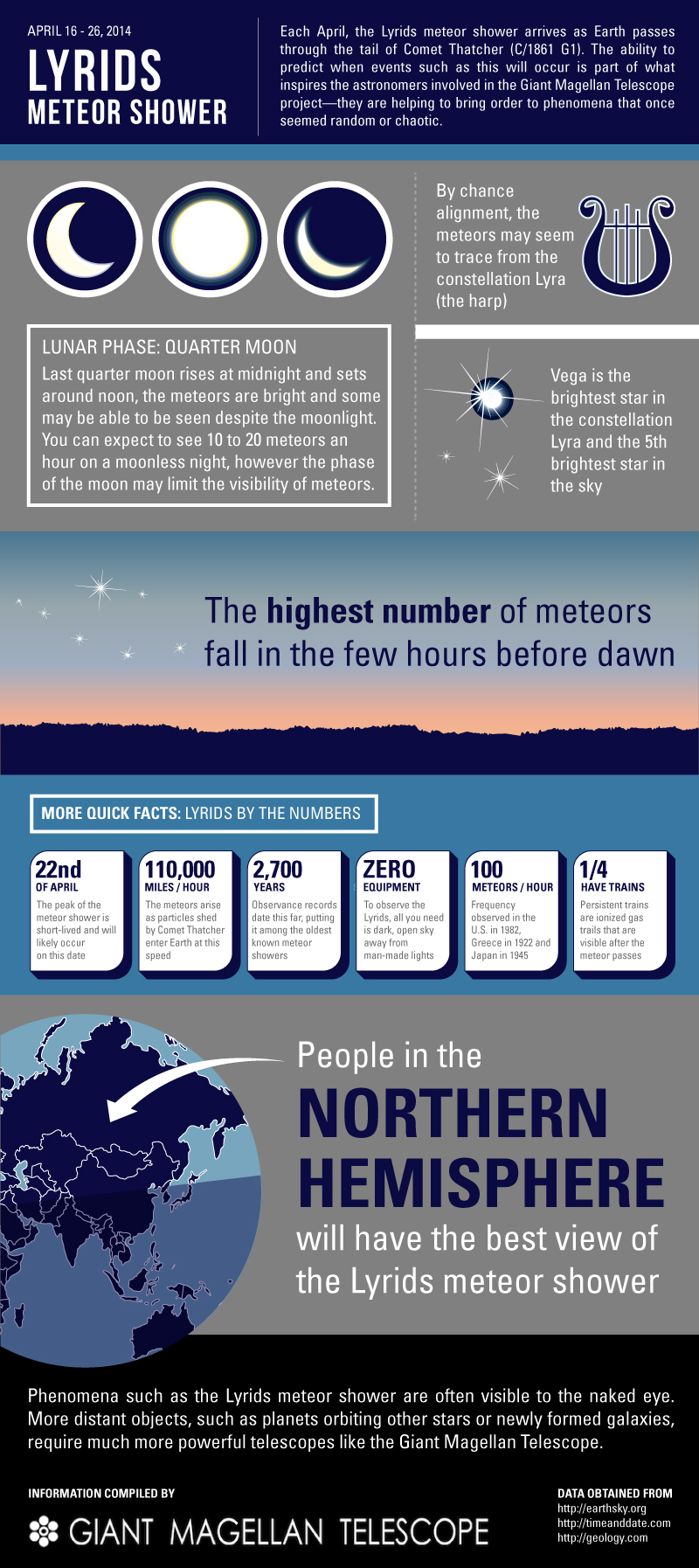

The annual Lyrid meteor shower occurs every year when Earth passes through debris left behind by Comet Thatcher, which makes a full orbit of the sun once every 415 years. At its peak this year — which is expected to happen in the pre-dawn hours Tuesday (April 22) — the Lyrid shower should produce about 20 meteors per hour. You can watch the Lyrid meteor shower webcasts on Space.com via the online Slooh community telescope and NASA.

The Slooh webcast will begin at 8 p.m. EDT (0000 April 22 GMT). You can also watch it directly on www.slooh.com. NASA's webcast will begin at 8:30 p.m. EDT (0030 April 22 GMT) and last through the night. You can follow NASA's live webcast directly at:

http://www.nasa.gov/topics/solarsystem/features/watchtheskies/lyrids-ustream-2014.html. Both webcasts depend on clear skies for good views of the meteor shower. [Amazing Lyrid Meteor Shower Photos from 2013 (Gallery)]

"Best viewing will be midnight until dawn on the morning of April 22, provided you have clear, dark skies away from city lights," NASA officials wrote in a skywatching advisory. "Northern Hemisphere observers will have a better show than those in the Southern Hemisphere."

The Lyrid meteor shower has been observed for nearly 2,600 years. Chinese astronomers were the first to record the meteor display in 687 B.C., Slooh representatives said in a statement.

"This is not one of the top meteor showers of the year like the Perseids and the Geminids, still the Lyrids produce around 20 meteors an hour, and they are moderately fast — coming in at 110,000 miles per hour," Slooh astronomer Bob Berman said in a webcast advisory. "That's about 30 miles per second, which is nearly 60 times faster than a rifle bullet."

Stargazers in dark areas with clear weather could see some meteors. But the waning gibbous moon will probably wash out most of the show this year, meteor shower expert Bill Cooke of NASA told Space.com. "I would not set high expectations," Cooke said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

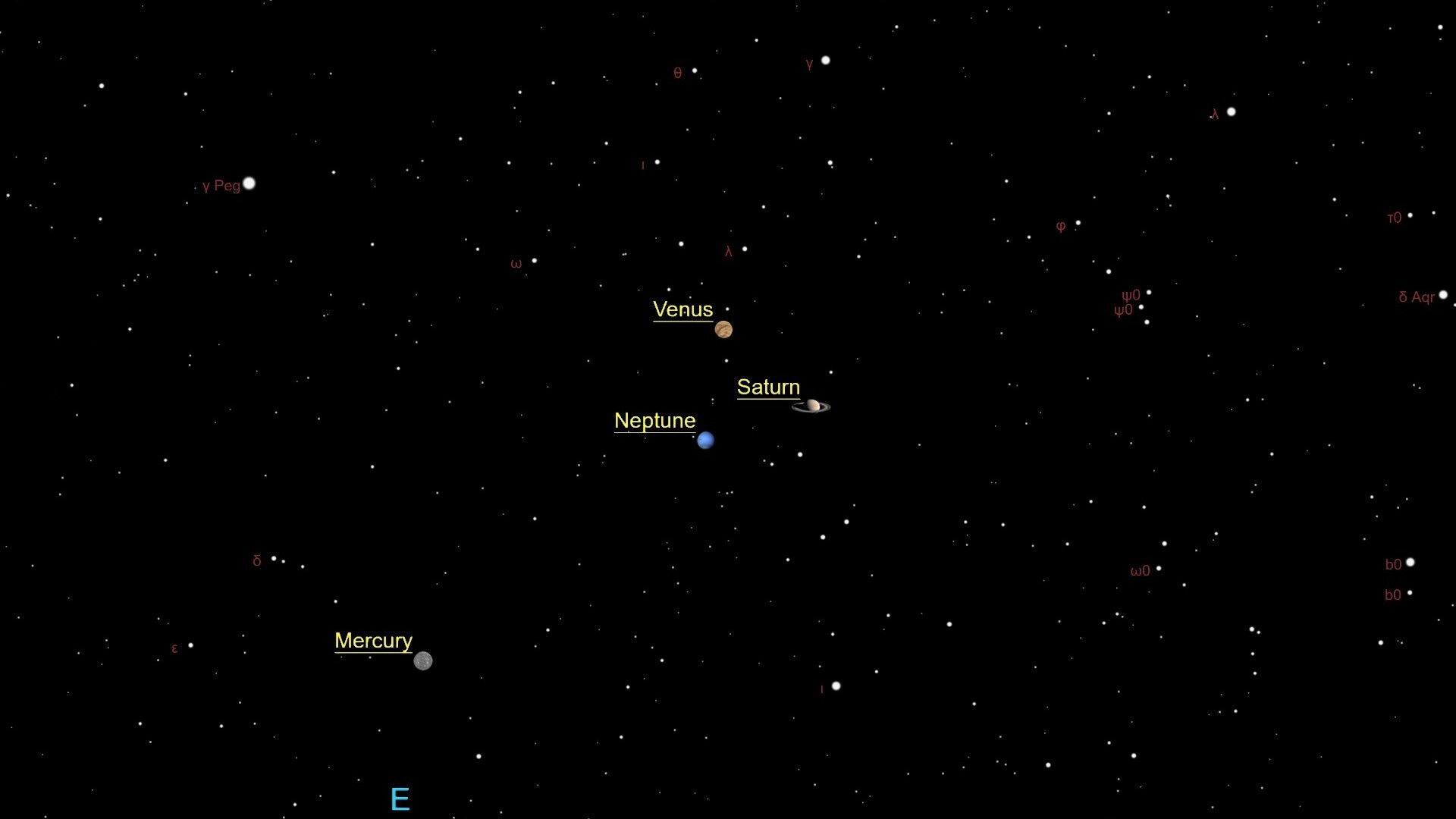

Lyrid meteors appear to emanate from the star Vega in the constellation Lyra, the Harp.

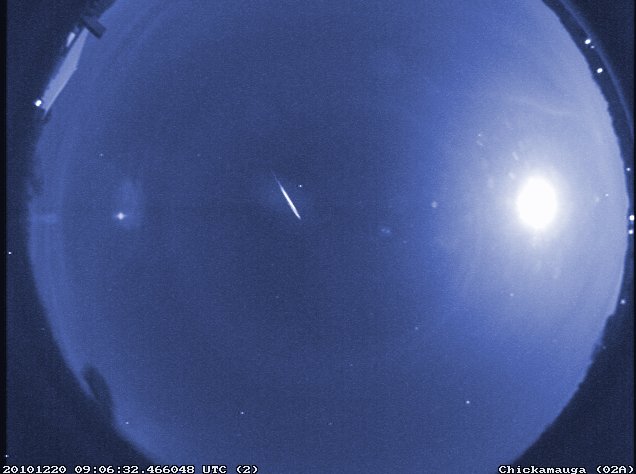

Meteor showers are created when pieces of space debris strike Earth's upper atmosphere. The bits of dust and rock heat up to extreme temperatures and glow, creating the streaks seen during meteor showers. Meteors compress the air in front of them, which heats the air, and in turn, heats the bits of debris.

When in space, bits of space material — like the debris that creates the Lyrid meteor shower — are known as meteoroids. As they streak through the atmosphere, they are called meteors and any bits of rock that make it to Earth's surface are labeled meteorites.

Editor's Note: If you snap a great photo Lyrid meteor shower that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.