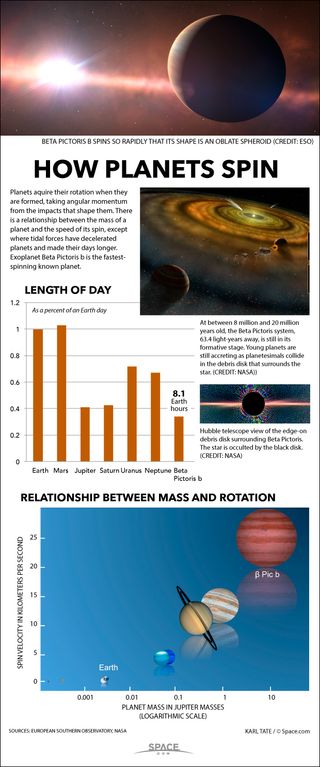

Astronomers have measured the rotation rate of an alien planet for the first time ever, finding that a huge Jupiter-like world called Beta Pictoris b has a day lasting just eight hours.

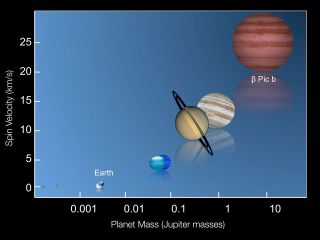

The equator of Beta Pictoris b, a gas giant about 10 times more massive than Jupiter, is moving at about 62,000 mph (100,000 km/h), researchers said — far faster than that of any planet in our solar system. In fact, Beta Pictoris b is the fastest-spinning planet yet seen.

In comparison, Jupiter's equator is traveling at about 29,000 mph (47,000 km/h), while Earth's is moving at just 1,060 mph (1,700 km/h). Days on these two familiar planets last about 10 hours and 24 hours, respectively. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

"It is not known why some planets spin fast and others more slowly, but this first measurement of an exoplanet’s rotation shows that the trend seen in the solar system, where the more massive planets spin faster, also holds true for exoplanets," study co-author Remco de Kok, of Leiden Observatory and the Netherlands Institute for Space Research, said in a statement. "This must be some universal consequence of the way planets form."

The researchers used the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile to study Beta Pictoris b, which lies 63 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pictor (The Painter's Easel). You can zoom in on Beta Pictoris b's parent star in this video.

The VLT spotted the molecular fingerprint of carbon monoxide in the giant planet's atmosphere. Further, this carbon monoxide signal was shifted and broadened considerably as a result of Beta Pictoris b's rotation, much as the sound waves emitted by a police car's siren shift as the vehicle approaches and passes a stationary observer.

The nature of this signal shift is consistent with a superfast spin that results in an 8-hour day for the huge exoplanet. (Interestingly, that day will likely get shorter in the future. Beta Pictoris b is an extremely young world — just 20 million years old, compared to 4.5 billion years for the Earth — that should shrink and cool as it ages, ramping up its spin rate considerably, researchers said.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new study could help astronomers get a better handle on how planets take shape and evolve.

"What this tells us about planet formation is not clear to me, but the accretion of angular momentum is definitely an important factor during formation," study lead author Ignas Snellen of Leiden Observatory told Space.com via email. "Planet formation models will have to be able to reproduce this behavior."

Snellen and his team needed just one hour of VLT observing time to pin down Beta Pictoris b's rotation rate, suggesting that the planet won't be in a class by itself for long.

"I think that maybe the most exciting aspect of this paper is the relative ease with which we performed these observations," Snellen said. "It means that in the coming years we will be able to measure the spin velocity of a whole sample of young gas giant planets."

The technique should also allow astronomers to make detailed global maps of exoplanets using giant future instruments such as the European Extremely Large Telescope, which is slated to come online in the early 2020s, researchers said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.