First 'Sibling' of Sun Found

Astronomers have likely discovered the first sibling of the sun, a star born from the same cloud of gas and dust as the one that lights Earth's days.

Finding more solar siblings could help shed light on how the solar system came to harbor life, researchers said, adding that life may even teem on the planets circling such sister stars.

Stars are typically born alongside many siblings within giant clouds of gas and dust known as stellar nurseries. The sun was probably born in a cluster containing 1,000 to 10,000 stars. [The Sun in HD: Latest Photos by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory]

At first, sibling stars remain near each other, as is the case with the constellation known as the Pleiades or Seven Sisters, which is dominated by hot, bright stars that formed within the last 100 million years. The stellar cluster the sun was born in broke up long ago, however, with its siblings now scattered across the Milky Way.

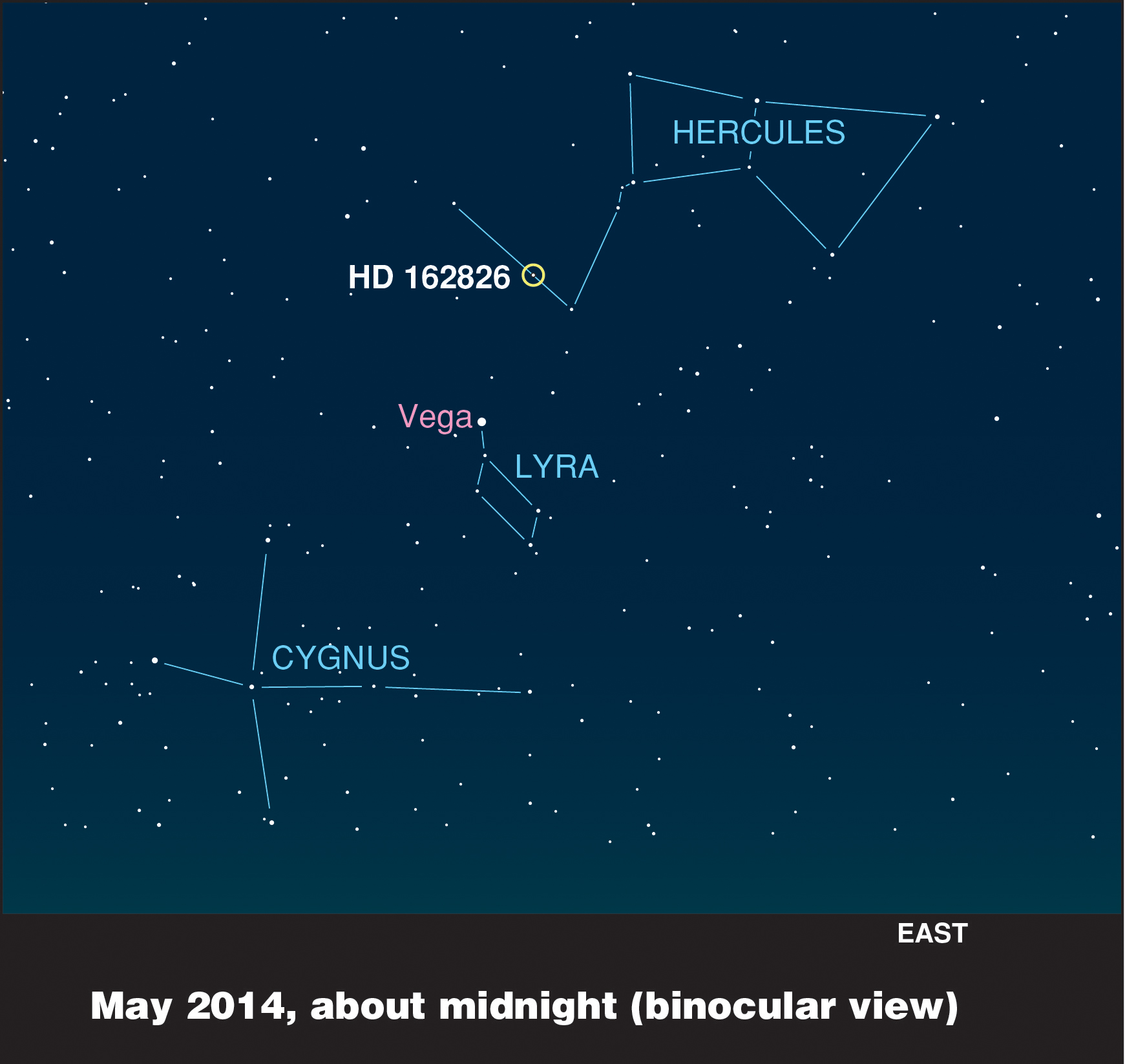

The solar sibling researchers discovered is a star called HD 162826, located 110 light-years away in the constellation Hercules. This star is not visible to the naked eye, but it can be seen with low-power binoculars, near the bright star Vega.

Finding solar siblings

To recognize solar siblings, researchers need to detect at least two identifying features: similar chemical compositions and orbits that suggest they might share the same birthplace as the sun.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The research team examined the chemical makeup of 30 possible solar siblings previously identified by several groups around the world. Scientists can detect what elements a star possesses by looking at its light, which comes in a wide variety of wavelengths, some visible and many invisible. The wavelengths of light that an element gives off can act like a fingerprint, revealing the identity of the material in question.

The chemical compositions of the sun and its siblings are similar because the stellar nursery in which they formed was contaminated by material given off by nearby stars, and potentially by remnants of stellar explosions known as supernovas. [Great Images of Supernova Explosions]

"The ratio of abundances of a few chemical elements are key parts of this chemical fingerprint — barium and yttrium, for example," said lead study author Ivan Ramirez, an astrophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin.

After the scientists analyzed the chemistry of these stars, they were left with two potential candidates. They next modeled the orbits of these stars around the center of the Milky Way. They found one of these candidates, HD 162826, may have shared the stellar nursery the sun was born in about 4.6 billion years ago.

"It's exciting to have been able to find even one solar sibling," Ramirez told Space.com. "The expectation was that we wouldn't be able to discover any — we expect the number of these stars that we can find to be very low."

Although HD 162826 is a sibling of the sun, it is not a solar twin. Rather, this star is 15 percent more massive than the sun.

Scientists began observing HD 162826 more than 15 years ago. This prior work suggests no giant planets orbit the star. However, it may possess smaller rocky worlds like Earth, Mars or Venus.

Now that Ramirez and his colleagues have created a road map for how to identify solar siblings, they suggest that many more may be discovered with the help of the European Space Agency's Gaia mission, which launched in December.

Gaia will use a billion-pixel camera to survey more than 1 billion Milky Way stars over the next five years, amounting to about 1 percent of the stars in the galaxy. Using Gaia, the number of potential solar siblings astronomers can detect will increase by a factor of 10,000, Ramirez said.

"We're helping to set the stage for the best way to find solar siblings," Ramirez said.

Searching for life

This cosmic family reunion will help astronomers understand where and how the sun formed, which could yield insights into how the solar system became hospitable for life.

"By pinning down the location of the sun's birth — say, if it was close to the center of the galaxy or farther away — that will tell us what the environment the solar system formed in was like, and potentially if that had any implications on the origin of life," Ramirez said.

Additionally, there is a chance — "small, but not zero," Ramirez said — that solar siblings could host worlds that are home to life. He noted that matter could have traveled between solar systems, with Earth getting seeded by or seeding other planets with the ingredients for life or potentially even life itself.

"It could be argued that solar siblings are key candidates in the search for extraterrestrial life," Ramirez said.

The scientists will detail their findings in the June 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us