Heart of Darkness: Strange Gas Stream Blots Out Galaxy's Bright Core (Video)

The bright center of a distant galaxy strangely and unexpectedly darkened recently, and now scientists think the culprit was a rare, powerful stream of gas blowing in front of it, eclipsing its heart.

This new finding may also provide insights into the workings of supermassive black holes and how they influence their galaxies, scientists added. You can watch a video detailing the new galaxy finding on Space.com.

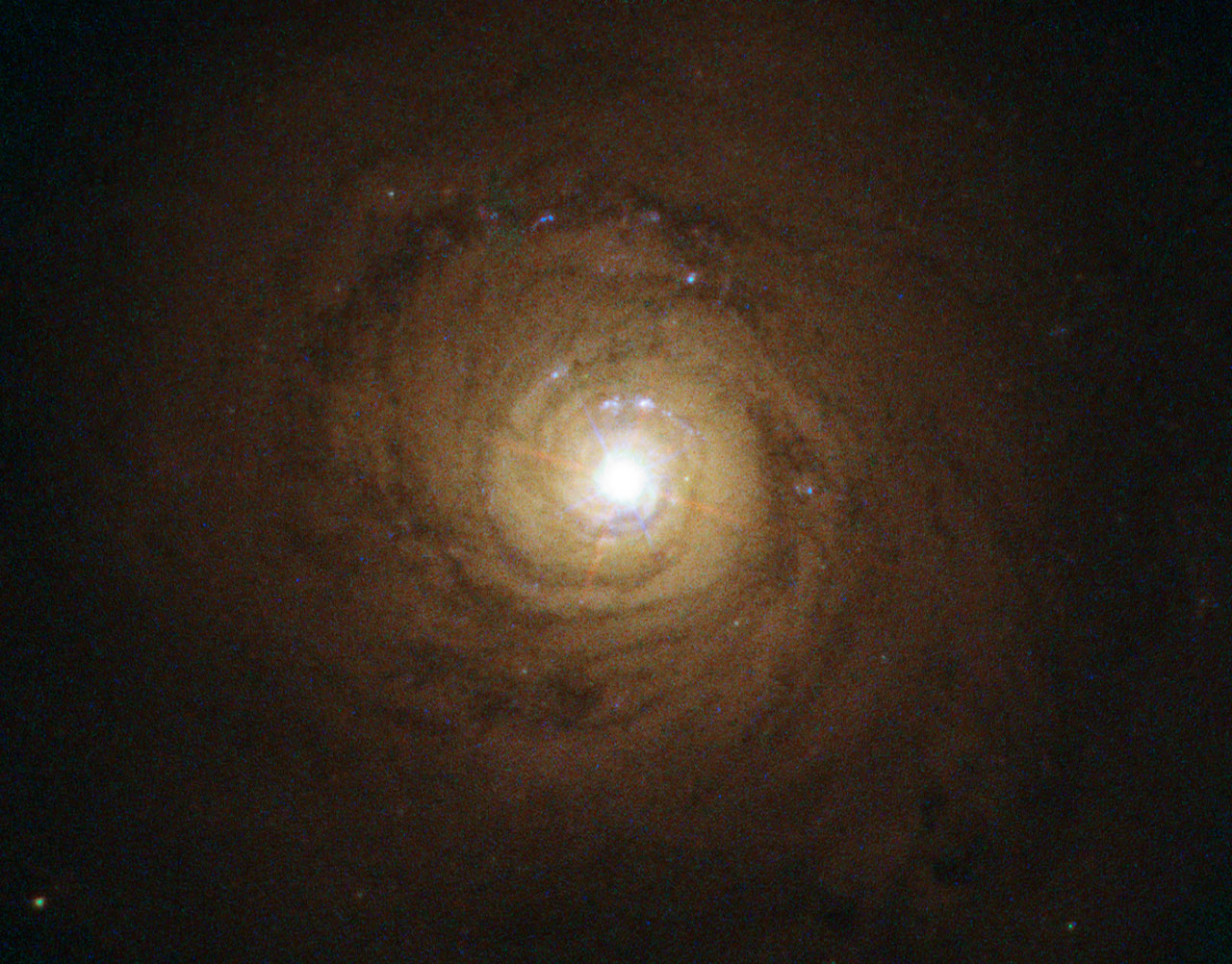

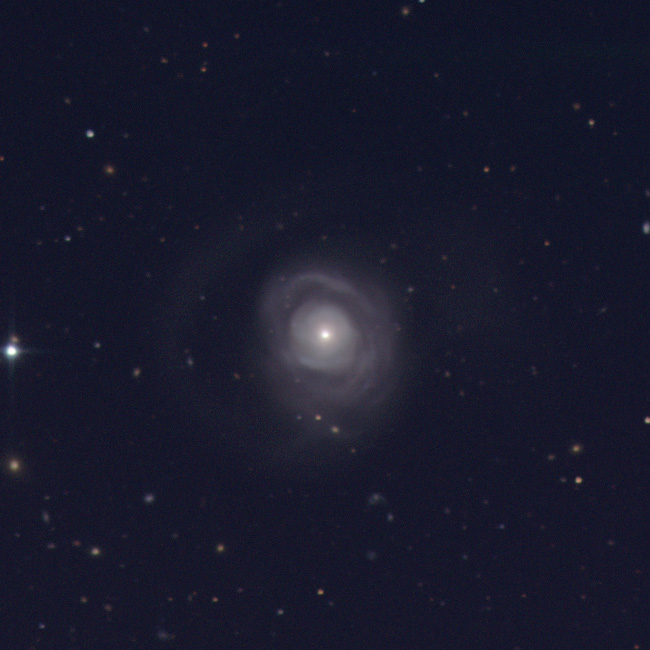

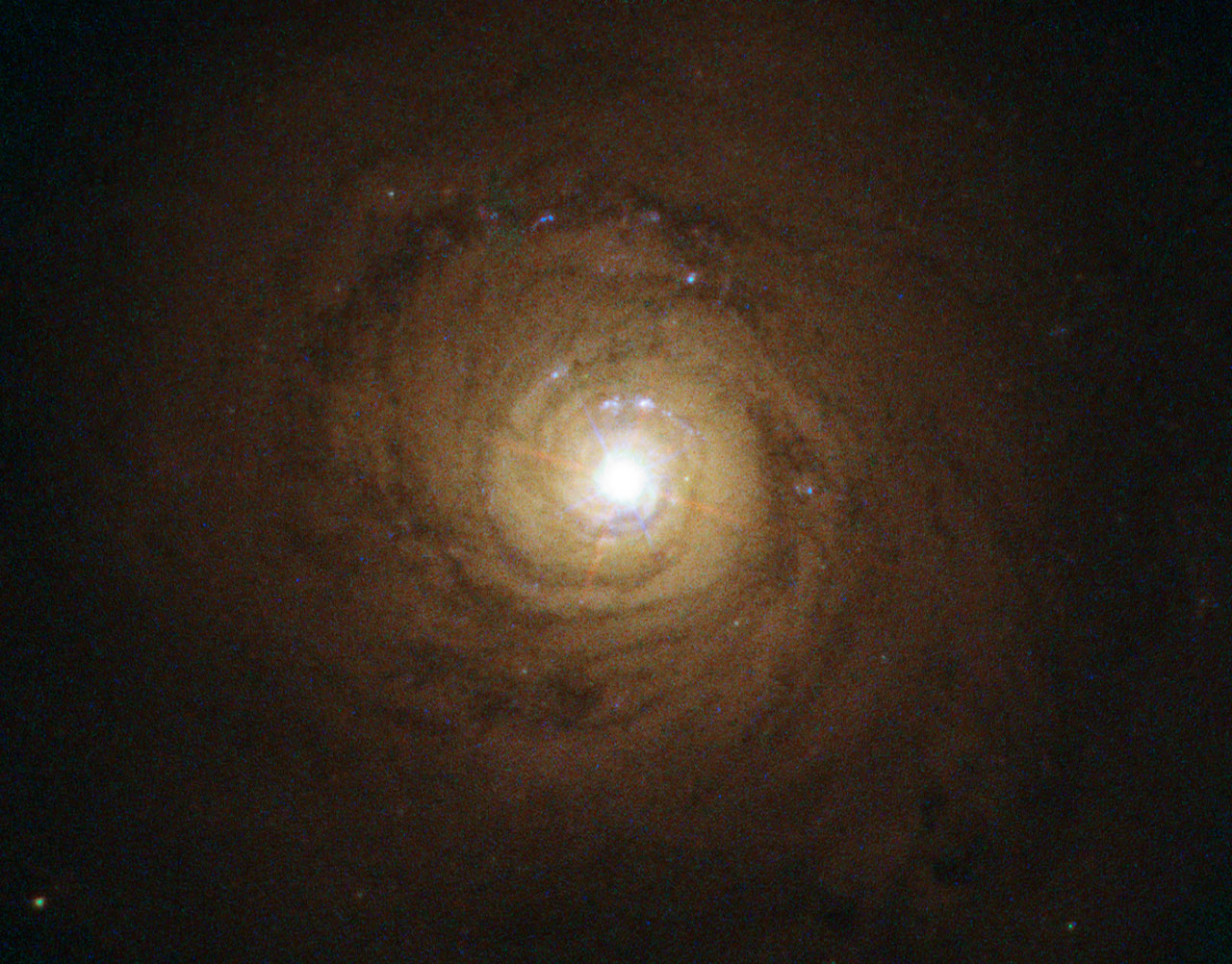

Astronomers examined a well-known galaxy called NGC 5548, which lies about 245 million light-years away from Earth in the constellation Boötes, the Herdsman. The center of that galaxy is bright, due to light emitted from matter rushing toward its core, a supermassive black hole about 65 million times the mass of the sun. [See amazing photos of galaxies throughout the universe]

In 2013, astronomers noticed that something eclipsed the light from NGC 5548, blocking 90 percent of the X-rays emitted by the supermassive black hole.

"Astronomers have been looking at this galaxy for decades, and everyone expected it to behave normally, so seeing this galaxy's center change to a completely different state was surprising and exciting," lead author of the new research Jelle Kaastra, an astronomer at the SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research in Utrecht, Netherlands, told Space.com.

To find out more about why this galaxy's core went dark, astronomers examined it with six different NASA and European Space Agency observatories — the Hubble Space Telescope, XMM-Newton, Swift, NuSTAR, Chandra and INTEGRAL — from May 2013 to February 2014.

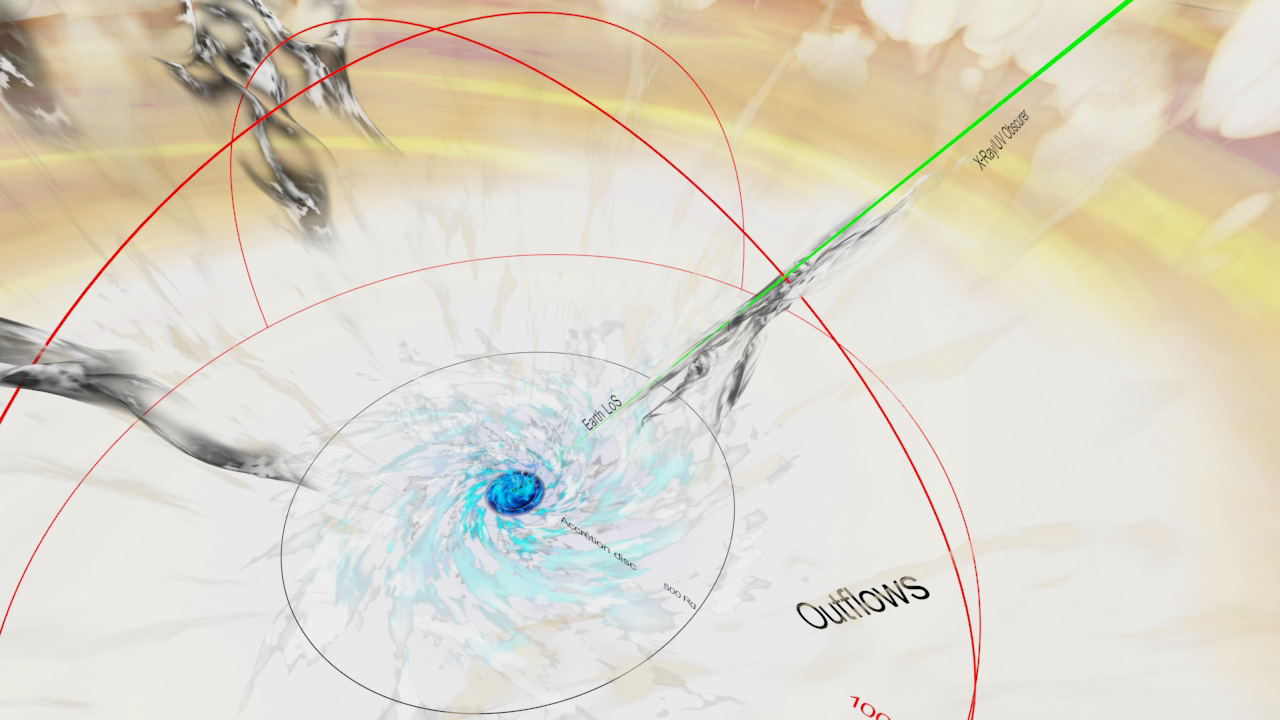

After comparing their observations to data from 2002, when nothing seemed to eclipse that galaxy's nucleus, the scientists created a model to account for the eclipse. The researchers suggest the culprit was a fast-moving and clumpy stream of gas moving up to 11 million mph (18 million km/h).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This is a fairly rare event, not seen in the decades we have been looking at it," Kaastra said.

This streamer of gas began obscuring NGC 5548 sometime between August 2007 and February 2012, and has lasted sometime between 2.5 and six years.

"It has traveled a distance of at least 100 billion kilometers [62 billion miles]," Kaastra said. "It probably has an elongated structure, with its width just 1 to 10 percent of its length."

Although scientists had seen other galaxies with gas streams near black holes, "this is the first time we've seen a stream like this move into the line of sight," study co-author Gerard Kriss of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, said in a statement. "We just happened to get lucky. With most objects like this, you don't normally see this kind of event."

Matter falling onto a black hole gets hot and emits ultraviolet rays and X-rays. The ultraviolet radiation can launch powerful winds outward. Scientists had known a wind persistently blew from the center of NCG 5548 for two decades, but this newfound gas stream travels up to five times faster than this persistent wind. Furthermore, this gas stream originates much closer to that galaxy's nucleus than the persistent wind — only a few light-days away. (A light-day is the distance light travels in a day, equal to about 16 billion miles [25.9 billion kilometers].)

"This new stream is most likely gas that comes from the accretion disk, the disk of gas that is swirling in toward a black hole," Kaastra said. "This disk is turbulent, filled with all kinds of bubbles and instabilities that can launch gas from the disk."

The researchers say these findings are the first direct evidence for the long-predicted shielding process that is needed to accelerate black hole winds to high speeds. Past research suggests these winds come into existence only if their starting point is shielded from X-rays — the newly discovered eclipsing stream could provide such protection.

Black hole winds can be powerful enough to blow off gas that otherwise would have fallen onto the black hole. This means black hole winds can regulate both the growth of the black hole and its galaxy. "Learning more about these powerful winds can shed light on galactic evolution," Kaastra said.

In the future, Kaastra said, researchers should try to find more of these powerful gas streams to find out how often they happen and learn more about what causes them.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (June 19) in the journal Science.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us