Saturn's Moon Titan Sheds Light on Hazy Alien Planets

By peering into the haze of Saturn's huge moon Titan, scientists could learn more about how the atmospheres of alien worlds behave.

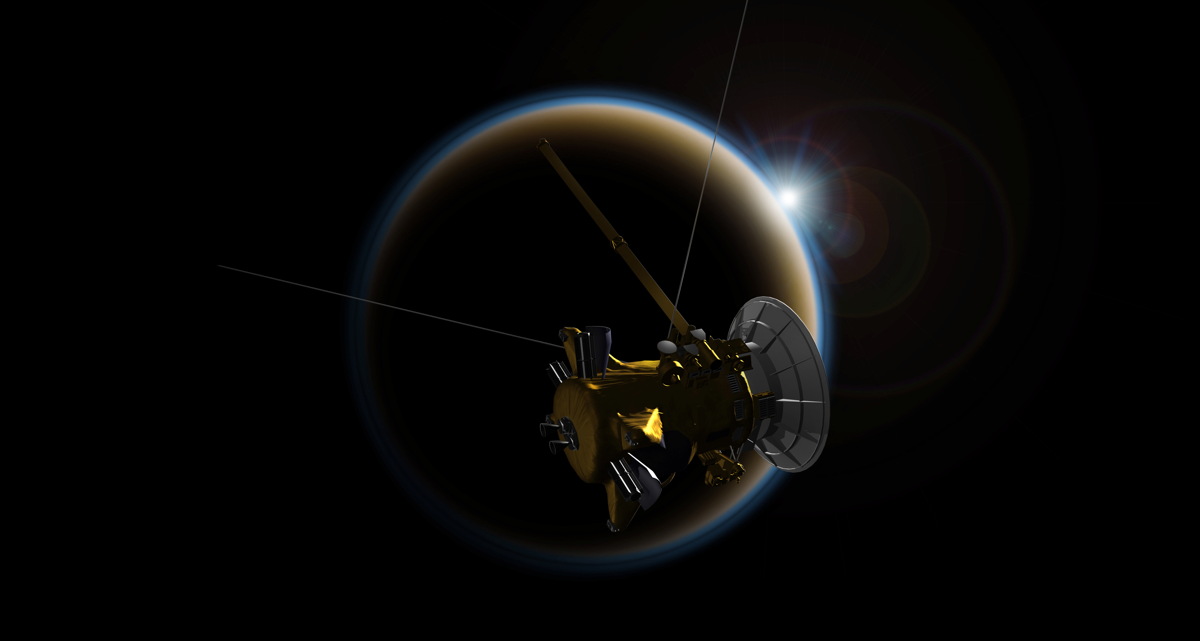

A team of scientists has recently developed a technique to help unscramble the messages encoded in the light signatures of exoplanets located light-years from Earth, but wanted to test it out a little closer to home first. The scientists used data collected from 2006 to 2011 by the Cassini spacecraft in the Saturn system to examine Titan's hazy atmosphere and learn more about how it works.

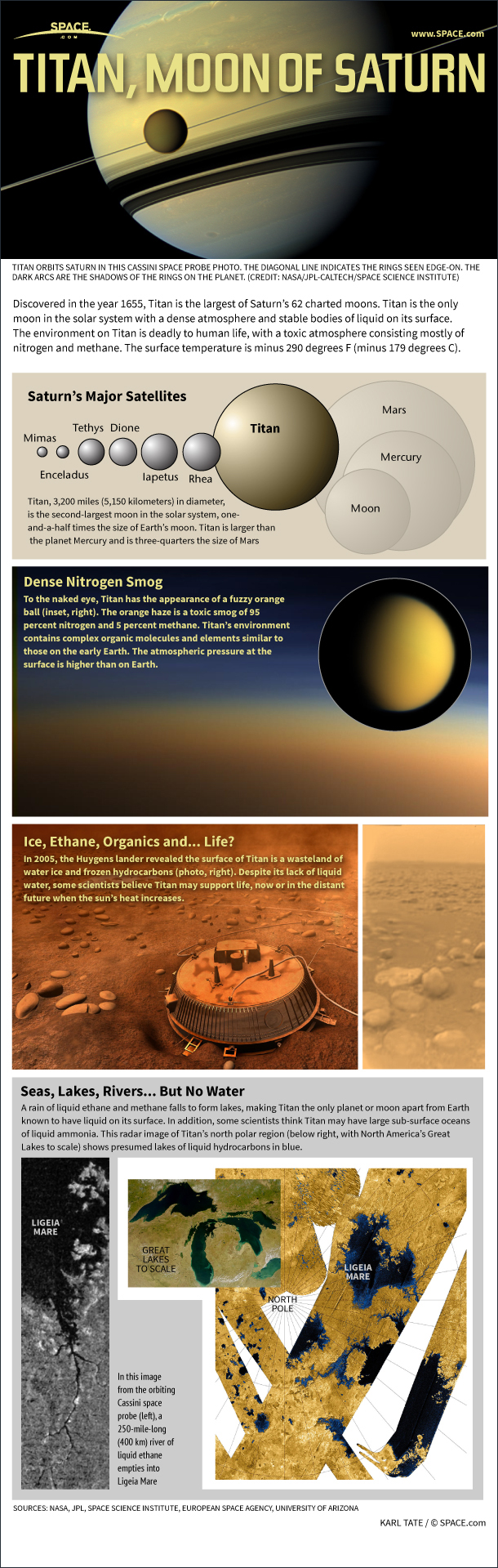

Scientists have known for a while that many exoplanets probably have atmospheres obscured by haze and smog. That haze creates a problem for astronomers wanting to study those far-away worlds. Just as scientists try to understand the properties of stars by analyzing the light they emit, scientists study alien worlds by observing what happens to light as it passes through those planets' atmospheres. Scientists wait until the exoplanet passes, or transits, in front of its star, then gather the light with a telescope and use a prism to separate the light into its individual wavelengths, in the process gathering information about the planet's atmosphere, including its temperature, structure and overall composition. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

"It turns out that there's a lot you can learn from looking at a sunset," said Tyler Robinson in a NASA statement. Robinson, a postdoctoral research fellow at NASA's Ames Research Center, in California, led the team that produced the results.

But if the exoplanet's atmosphere is hazy, the measurements gathered might not accurately reflect what the atmosphere is really like. For a while, scientists thought that the haze would affect atmosphere measurements, but modeling the effects in their calculations would be complicated and take a lot of computing power. To make the calculations simpler, astronomers downplayed the haze's effect.

Scientists realized, though, that they could learn more about how the haze behaves by studying smoggy worlds in our own solar system, therefore, they turned their attention to Titan.

"Their analysis provided results that include the complex effects due to hazes, which can now be compared to exoplanet models and observations," according to a NASA statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Specifically, the analysis revealed that scientists might be able to get reliable information about only the upper reaches of an exoplanet's atmosphere. For Titan, that region equals 90 to 190 miles (150 to 300 kilometers) above the moon's surface. The team also found that haze affected short wavelengths of light more than other wavelengths. Scientists had previously believed that haze affected all wavelengths similarly.

The technique devised by Robinson and his team can be applied to measurements taken of any extraterrestrial world, including planets like Mars and Saturn.

"Ty's results are proof of concept that you can remotely detect features of molecules on distant, cold worlds," Sarah Ballard, the NASA Carl Sagan Fellow in Astronomy at the University of Washington, said. "I feel a renewed hope that mankind is one step closer to detecting the signatures of faraway life."

Follow Raphael Rosen on Twitter. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Raphael Rosen is a science and technology writer. He has written for the Wall Street Journal, NASA, the World Science Festival, Space.com, EARTH, Discover, Sky & Telescope, Scholastic Science World, the American Technion Society, SciArt in America, TheFix.com, the Encyclopedia of Life, Princeton University, and the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. He has also written a children’s book about outer space.