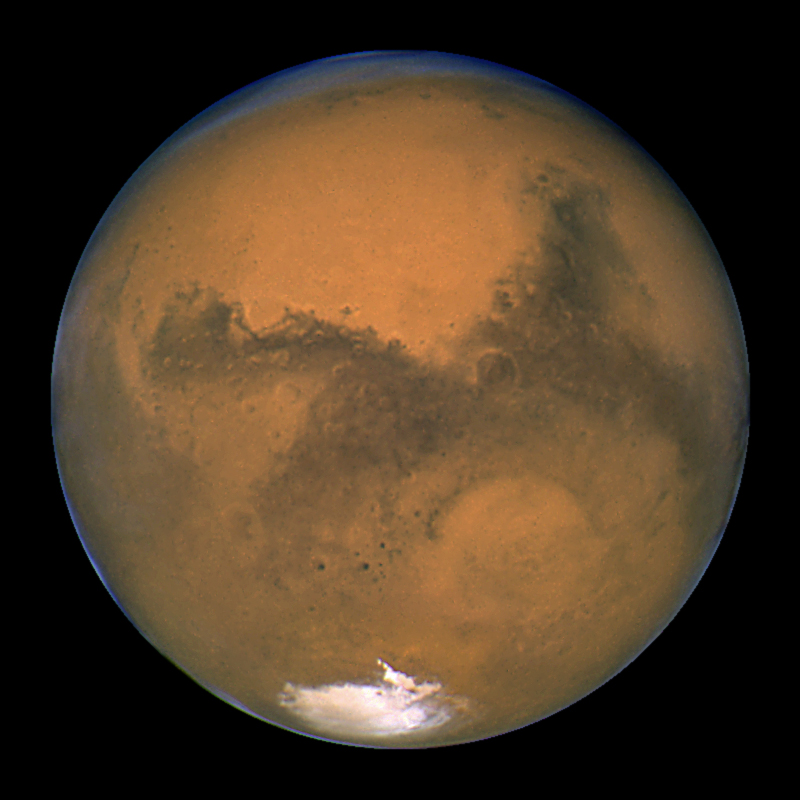

NASA's next Mars rover could help humans get a foothold on the Red Planet.

Most of the seven instruments for the six-wheeled robot, which is scheduled to launch toward Mars in 2020, are designed to help scientists identify and sample rocks that may harbor evidence of past Mars life, NASA officials announced Thursday (July 31). The rover will cache such samples for a potential return to Earth in the future.

But one instrument aboard the 2020 Mars rover will generate oxygen from the Red Planet's atmosphere, demonstrating technology that could both keep astronauts alive on Mars and help them launch into space when it's time to go home. [NASA's 2020 Mars Rover in Pictures]

"This is a real step forward in helping future human exploration of Mars by being able to produce your oxygen on the surface of Mars," Michael Meyer, lead scientist for the Mars Exploration Program at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., told reporters Thursday.

Breathable air and rocket fuel

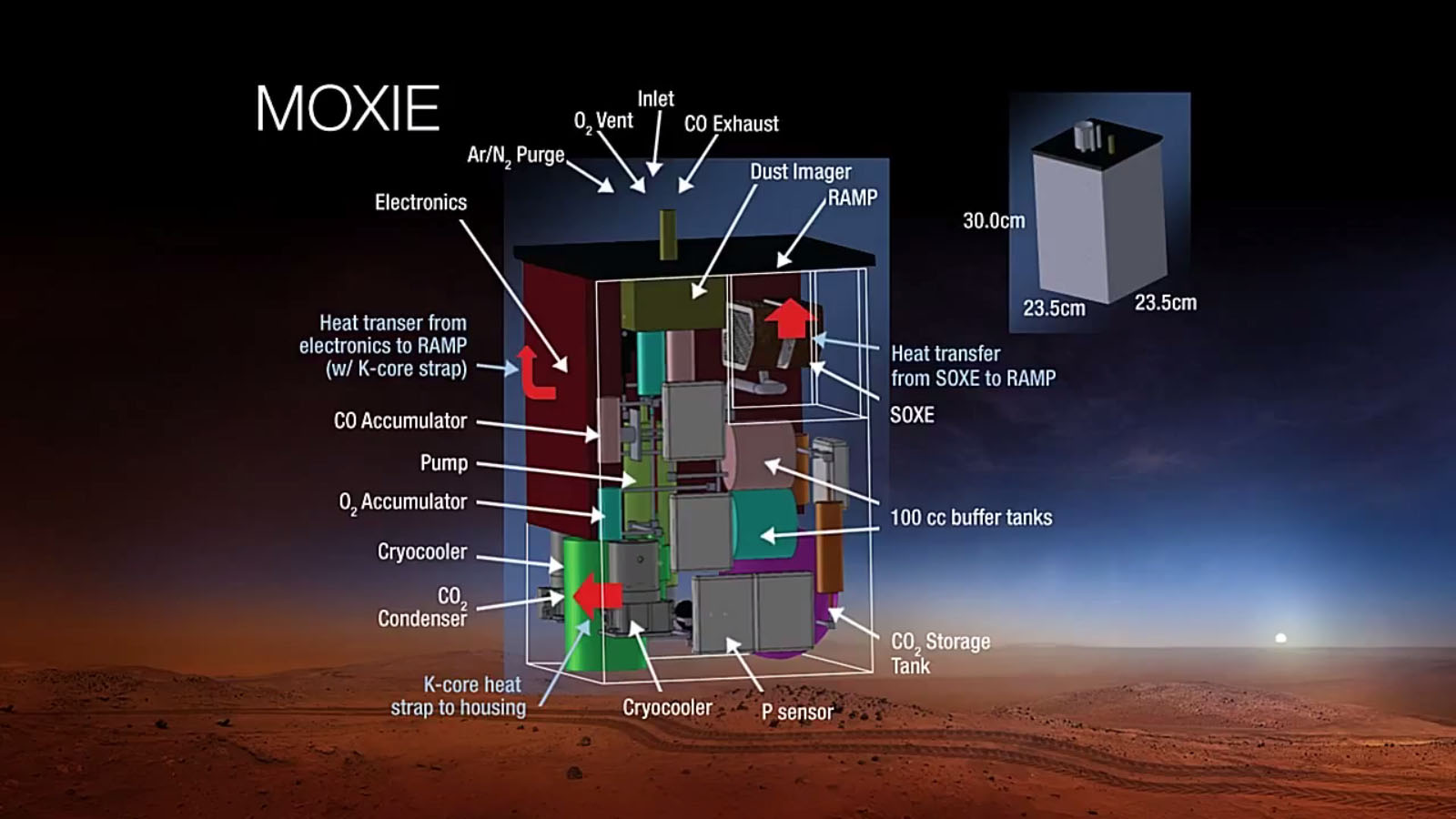

The instrument is known as MOXIE (Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resources Utilization Experiment). It will pull carbon dioxide from the thin Martian atmosphere, which is composed of about 96 percent CO2, and turn it into pure oxygen and carbon monoxide, said Michael Hecht of MIT, the instrument's principal investigator.

"This is essentially a fuel cell run in reverse," he said. (Hecht added that CO2 is often a product of fuel cells, which generate electricity from fuels such as hydrogen.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA has made demonstrating this capability a key priority, as the agency aims to put boots on Mars in the 2030s and wants its pioneering human outpost to be as self-sufficient as possible. (Decreasing or eliminating the need for oxygen resupply from Earth would also cut costs, of course.)

In a future manned mission, astronauts would breathe some of the oxygen produced on the Red Planet. But much of the gas would be stored for use as an oxidizer, helping burn the rocket fuel that would launch spacecraft from the surface of Mars back to Earth, Hecht said.

Future experiments may even attempt to generate rocket fuel itself — methane, for example — from Martian materials, NASA officials said.

"But the first step, before we go pursue all of these things — let's take one that's fairly simple, that can fit on this package, can fit on the rover," said Bill Gersteinmaier, associate administrator for the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA headquarters.

"Let's see what the efficiencies are," he added. "Let's understand — is there something we're really missing in the Martian environment that drives this a different way? Let's see what we can do with oxygen first, and then we'll do the plans for the other pieces as they fit together."

Scaling it up

If all goes according to plan, MOXIE will produce about 22 grams (0.78 ounces) of oxygen per hour and will operate on at least 50 different Martian days during the course of the mission, Hecht said.

"Part of the objective is to show that, as a factory, if you will, we can continue to operate at full or near-full capacity over the duration of the mission without degradation," Hecht said.

While establishing an oxygen factory on Mars may seem ambitious enough in its own right, Hecht has even bigger dreams.

"Our vision of a human Mars mission starts with landing a small nuclear reactor and a scaled-up version of MOXIE, a hundred-times scale," he said. "By the time the crew gets there, the reactor will be operational, the oxygen tank will be full and ready to take them home."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.