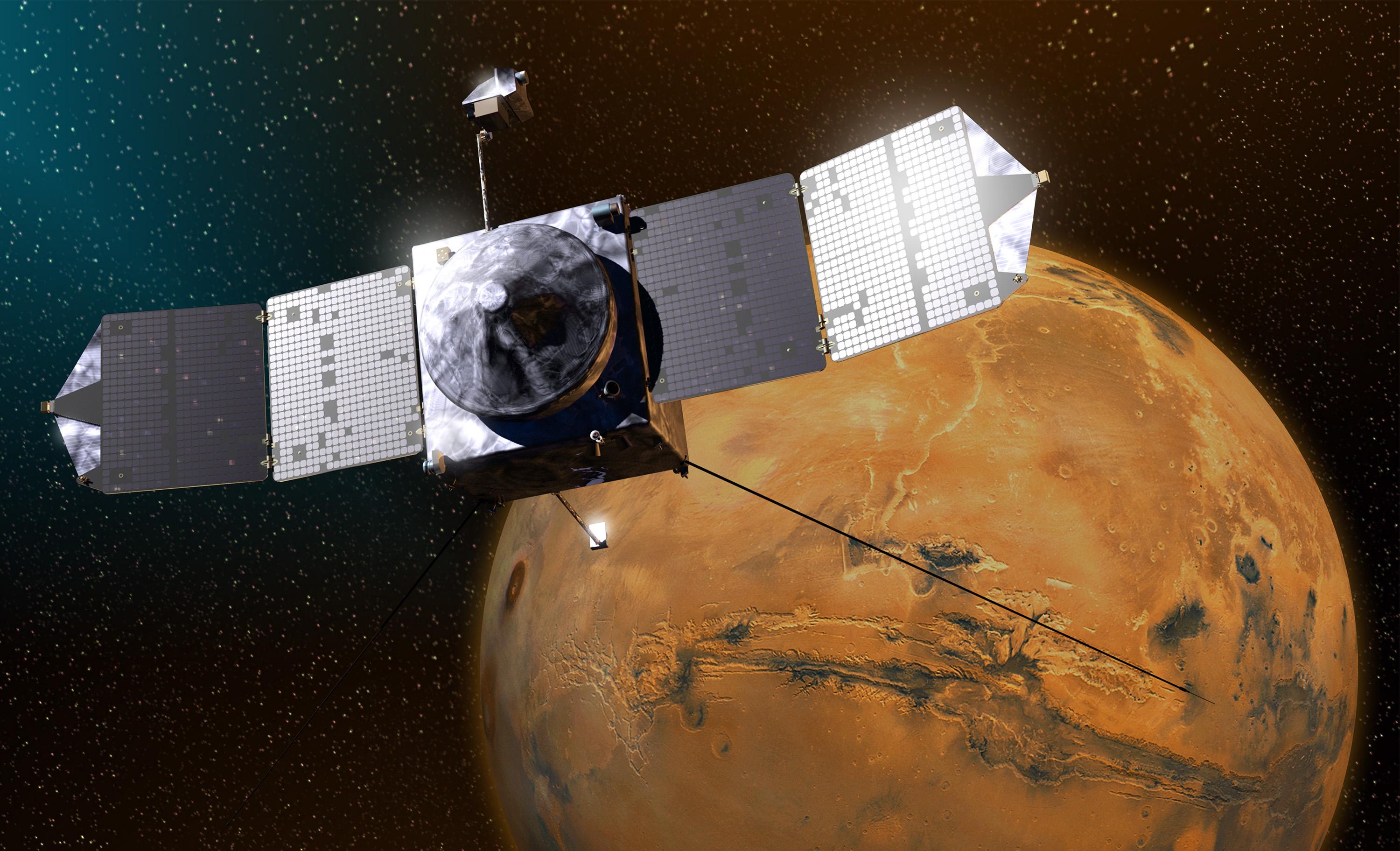

For two robotic spacecraft set to arrive at Mars over the next few days, the toughest task will be slowing down.

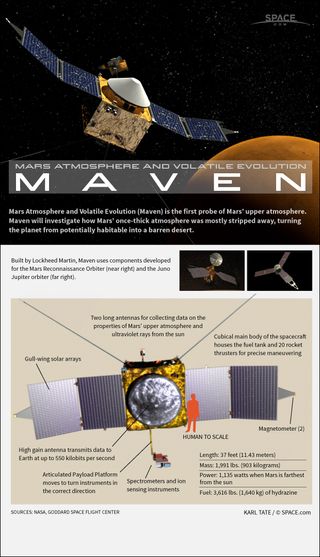

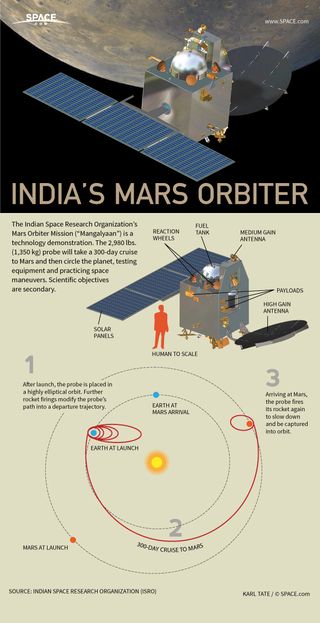

After streaking through space at mind-numbing speeds for 10 months, NASA's MAVEN spacecraft and India's Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) spacecraft will have to slam on the brakes if they hope to enter orbit around the Red Planet. Those captures are planned for Sunday and Tuesday nights (Sept. 21 and Sept. 23), respectively.

Both probes will need to fire their retrorockets successfully in an orbit-insertion burn, or they'll fly right on by Mars and be lost in the depths of space. [Photos: NASA's MAVEN Mission to Mars]

"Typically, that's a one-time event. There's no other need to fire that big rocket on the way to Mars until you get there," said Joe Guinn, manager of the Mission Design and Navigation Section at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, who is helping both the MAVEN spacecraft (short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) and MOM get to the Red Planet.

"So you're coming up on the biggest event of the mission, and it's the first time you've done it," Guinn told Space.com. "That's a challenge."

Margin for error

Fortunately, orbit-insertion burns don't have to be perfect to be effective. For Mars, such firings are typically designed to last 30 minutes or so, Guinn said, and executing about 95 percent of the burn should result in a successful capture.

"It's not terribly tight, but you can't sort of make it halfway and be OK," Guinn said. "You've got to get most of the way there."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And getting most of the way there is not a foregone conclusion. For instance, in August 1993, NASA lost contact with its Mars Observer orbiter just days before the craft was to reach the Red Planet. A leak during a pressurization test of the vessel's braking engines likely caused an explosion, scuttling the mission, Guinn said.

In another example, the engine on Japan's Akatsuki Venus probe failed during its December 2010 insertion burn, firing for just three of a planned 12 minutes. Akatsuki is now in orbit around the sun, and mission officials are aiming for another shot at Venus in 2015 or 2016.

Firing the braking engines properly is not the only challenge involved in getting a spacecraft to Mars orbit, of course. The vast distance between Earth and the Red Planet results in significant communications delays between Mars-bound spacecraft and ground control, up to 24 minutes one-way, depending on planetary alignments, Guinn said.

That means potential problems with a spacecraft cannot be identified, let alone fixed, immediately.

"So most of this is all scripted well in advance, and we practice it," Guinn said. "But it's hard to practice for every single contingency."

The relative infrequency of Mars mission launch opportunities poses another difficulty, he added. Mars and Earth approach each other closely enough to accommodate a relatively quick and efficient spaceflight just once every 26 months, complicating efforts to build up and retain institutional knowledge.

"There's quite a bit of turnover. People move on to other projects," Guinn said. "So there's a small group who actually carries forward all these lessons learned over time."

Martian landers and rovers

So getting a spacecraft to Mars orbit is not exactly routine. But putting a lander or rover down on the planet's surface is tougher still.

For starters, landed missions have to fly much more precisely during the final stages of their treks to Mars, said Guinn, who also worked on NASA's Phoenix mission, which successfully dropped a lander near the Martian north pole in May 2008.

With orbiters, "you only have to hit the target to [within] maybe 50 kilometers [about 30 miles], the target being some sort of altitude above Mars," Guinn said. But with lander or rover missions, he added, "we've got to hit that target to less than 10 kilometers [about 6 miles]."

Surface missions are also more complex, because they tote entry, descent and landing (EDL) systems to get their payloads through the Martian atmosphereand safely down to the ground. With greater complexity and an increased number of tasks (i.e., landing on Mars) comes a greater chance of something going wrong.

And Mars is a particularly tricky body to land on. Its atmosphere is 1 percent as dense as that of Earth at sea level — too thick for missions to rely solely on retrorockets to touch down, but too thin for just parachutes and air friction to do the job.

So NASA has employed EDL systems that combine parachutes with impact-absorbing air bags (which delivered the Spirit and Opportunity rovers safely to Mars in 2004), as well as a strategy mixing parachutes with a rocket-powered sky crane (which helped the 1-ton Curiosity rover touch down in 2012).

Agency engineers are also developing giant supersonic parachutes and friction-increasing "decelerators" that could (with the aid of a sky crane) land gear even heavier than Curiosity. Such a system will be necessary to put human habitat modules and other manned-mission infrastructure down on Mars, NASA officials say.

Learning from mistakes

Statistics suggest that the MAVEN and MOM teams should be pretty nervous about their upcoming orbital-insertion maneuvers: Only about 50 percent of the 40-plus robotic Mars efforts launched over the decades have achieved full mission success. (MOM's handlers have another reason for anxiety: They're leading India's first-ever Mars mission.) [Mars Explored: Missions Since 1971 (Infographic)]

But such a quick look at the stats doesn't tell the whole story. Many Red Planet failures came in the 1960s, when engineers were still learning how to get a robotic probe to another world. And a decent chunk of these misses came in missions mounted by the Soviet Union or its successor state, Russia.

NASA's track record has been better, especially lately. After the high-profile 1999 failures of the Mars Climate Orbiter and Mars Polar Lander, the agency has enjoyed a string of Red Planet successes with orbiters (Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) and landed craft (the Phoenix lander and the Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity rovers).

Engineers have learned a great deal from the successes and failures over the years, making Mars a less challenging target than it once was, Guinn said. Though sending a robot to the Red Planet is not yet a routine undertaking, it could be someday.

"We're on the road there," Guinn said. "We have definitely found some ways to make things less uncertain."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

Most Popular