See Uranus with a Shadowy Full Moon During Total Lunar Eclipse

Most of North America will witness a total eclipse of the moon Wednesday (Oct. 8), but the morning sky, weather permitting, will also hold a surprise for intrepid skywatchers interested in seeing another celestial body alongside the eclipsed moon.

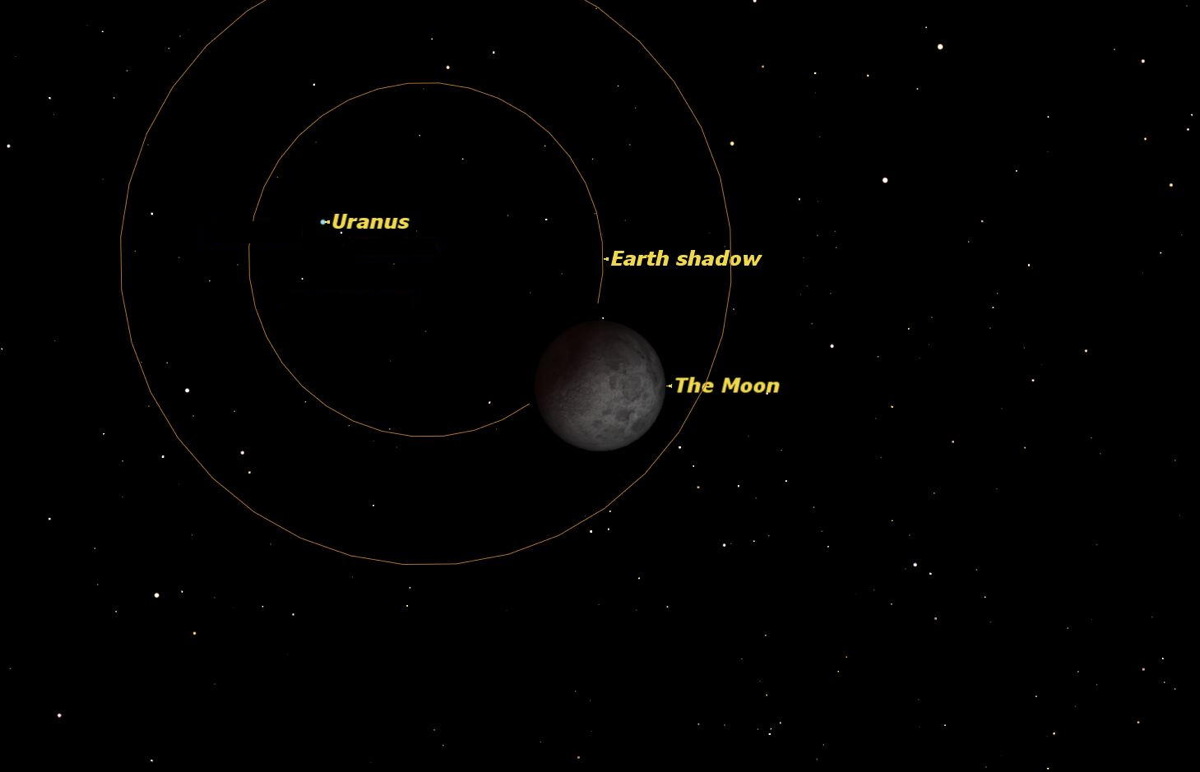

The planet Uranus will be in opposition to the sun on Tuesday evening, placing it very close to the full moon during the total lunar eclipse on Wednesday morning. Uranus is just around the limit of naked-eye visibility at magnitude 5.7, so interested observers will need binoculars to spot it. Even in the most powerful telescopes, Uranus is so far away that it will be only a tiny, featureless, blue-green disk.

The lunar eclipse officially begins when the moon slips into the faint outermost shadow of the Earth, called the penumbra. This shading, which occurs at 4:15 a.m. EDT (0815 GMT) on Wednesday, is so subtle that it might be invisible to the casual observer. [How to See the Total Lunar Eclipse (Visibility Maps)]

An hour later, at 5:15 a.m. EDT, the moon enters the Earth's darker inner shadow, or umbra. At that point, the shading will be quite obvious. By 6:25, the moon will be totally within the umbra, where it will remain until 7:24 a.m. EDT. At 8:34 a.m. EDT, Earth's satellite will be out of the umbra, and by 9:34 a.m. EDT, the eclipse will be over.

The only catch is that the Earth will continue rotating throughout the lunar eclipse, which will cause the moon to set in many locations before the eclipse is over. Because of this rotation, stargazers in the eastern parts of North America could miss some or all of the later parts of the eclipse.

For example, observers in New York City will see the moon set at 7:04 a.m. EDT, while the moon is still fully eclipsed. But in Los Angeles, the moon sets at 7:05 a.m. PDT, so skywatchers there will see the entire eclipse.

An eclipse of the moon is totally safe to view — with the naked eye, binoculars or a telescope. In fact, the best views of a total eclipse can be with the naked eye or low magnification on binoculars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Lunar eclipses are relatively easy to photograph, though skywatchters should use a telephoto lens to emulate the optical illusion whereby the moon appears much larger to the eye than it does to a camera. Be sure to remove any filters to avoid ghost images. (I once ruined a beautiful series of eclipse photos by leaving a filter in place, and got two moons in every shot.)

Photographing Uranus alongside the eclipsed moon will be a challenge because, even in full eclipse, the moon is still a very bright object, and will probably swamp Uranus' faint light.

Astronomers can't predict how dark the moon will be or what color the natural satellite will appear during the eclipse. The color and brightness of the moon during a total eclipse depend on weather conditions all around the world in the path the sun's light follows on its way past the Earth. Because of this, astronomers don't usually refer to a lunar eclipse as a "blood moon." Sometimes, the moon is tinted strongly red during an eclipse, but just as often it is yellow, copper or grey. Skywatchers will only find out for sure next Wednesday morning.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing picture of the Oct. 8 total lunar eclipse, you can send photos, comments, and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.