Here's What a Comet 317 Million Miles Away Looks Like to a Landing Spacecraft

Scientists and space fans alike held their collective breath today, as the European Rosetta mission's Philae probe landed on a comet for the first time in history. During those nerve-wracking few hours before landing, the Philae lander snapped a photo of its incoming landing site, revealing some amazing detail.

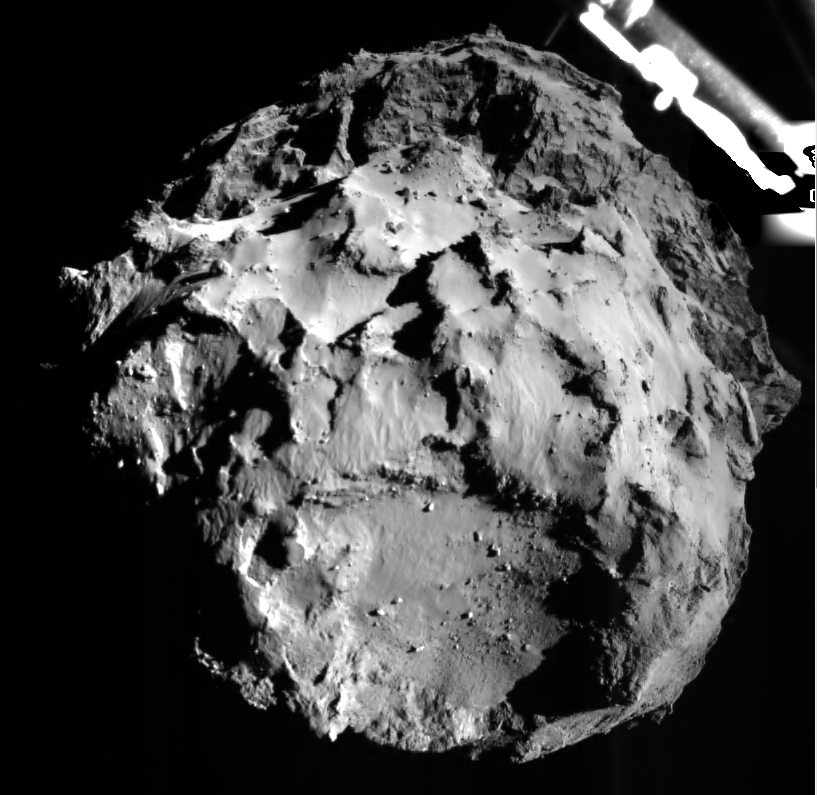

The image from Philae's historic landing success is the closest view of a comet ever captured. It shows the rugged surface of the 2.5 mile-wide (4 kilometers) Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, currently located 317 million miles (510 million km) from Earth.

The European Space Agency's Philae lander's arrival on Comet 67P/C-G was confirmed at about 11 a.m. EST (1600 GMT), making space exploration history as first soft landing on the surface of a comet. [Rosetta Comet Landing: Full Coverage]

The new comet photo came from Philae's ROLIS instrument, one of 10 different tools on the lander designed to study Comet 67P/C-G in extreme detail. One of Philae's legs also appears in the upper right corner of the picture.

Stefano Mottola of the Institute of Planetary Research at the German Aerospace Center and the lead scientist for ROLIS said in a press briefing that the image was taken about 3 km (1.8 miles) from the surface of the comet.

"The landing site is exactly in the middle," said Mottola. "And so we can confirm that the trajectory was correct and we had a safe landing. And more images are to come."

The Philae lander arrived at the comet aboard the Rosetta spacecraft, which left Earth in March 2004 and arrived at the comet in August 2014. The journey included a series of difficult maneuvers and a total distance of about 4 billion miles (6.4 billion km), according to ESA.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The image from ROLIS is the first in what is expected to be a detailed study of the surface and subsurface of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. Philae is equipped to not only photograph the comet, but drill into its surface to analyze its composition.

Comets like 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko formed more than 4.6 billion years ago, when the solar system was young and "unfinished," according to ESA. Unlike many of the planets and moons in our solar system, which have evolved since their formation, most comets have remained the same. Thus, comets serve as a sort of time capsule from the early universe.

Previous missions have chased after comets in our solar system. The International Cometary Explorer (ICE) passed through the tail of Comet Giacobini-Zinner in 1985, and then through the tail of Comet Halley in 1986. In 2005, NASA's Deep Impact mission dropped a probe onto the surface of Comet Tempel 1, creating an impact crator and kicking up debris. This allowed the second, orbiting probe to study the composition of the comet. The Deep Impact encounter is considered a "hard landing" because the object was not meant to operate after contact.

In a live webcast of the Philae landing, many representatives from ESA and other space agencies expressed their excitement about the event. David Parker, Chief Executive of the UK Space Agency said, "A simple way of summing it up for me is: science fiction has become science fact today. Or maybe a better way of saying it is: Hollywood is good, but Rosetta is better."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter