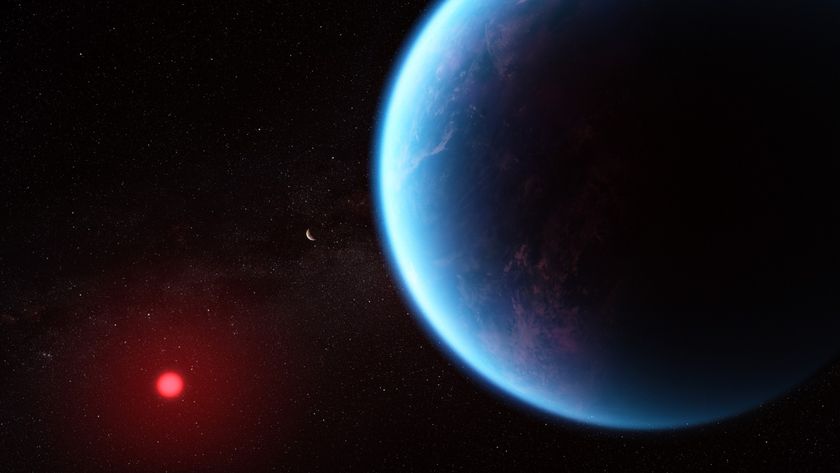

The world's most sensitive exoplanet imager has returned some amazing photos, as well as surprising results, just a year after opening its eyes.

The Gemini Planet Imager (GPI), which is installed on the Gemini South telescope in Chile, first started observing the heavens in November 2013 and didn't begin full science operations until this past November. But the instrument has already detected unexpected differences between two sister exoplanets and helped characterize the ring of dust and rocky bodies surrounding a young star, researchers announced Tuesday (Jan. 6).

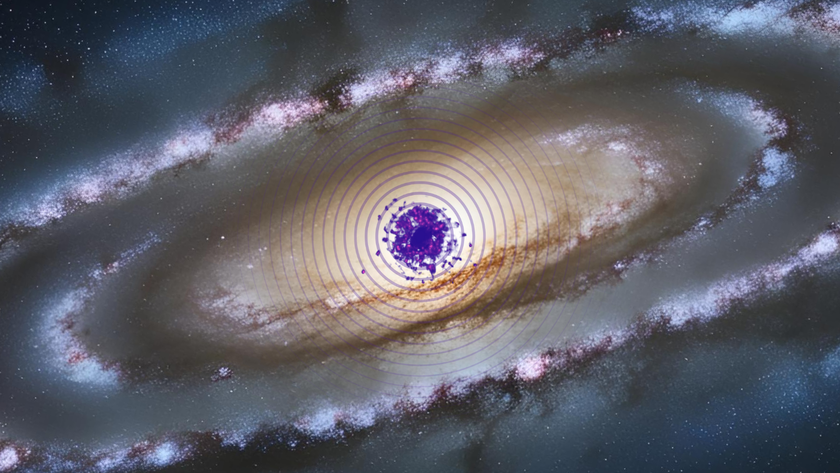

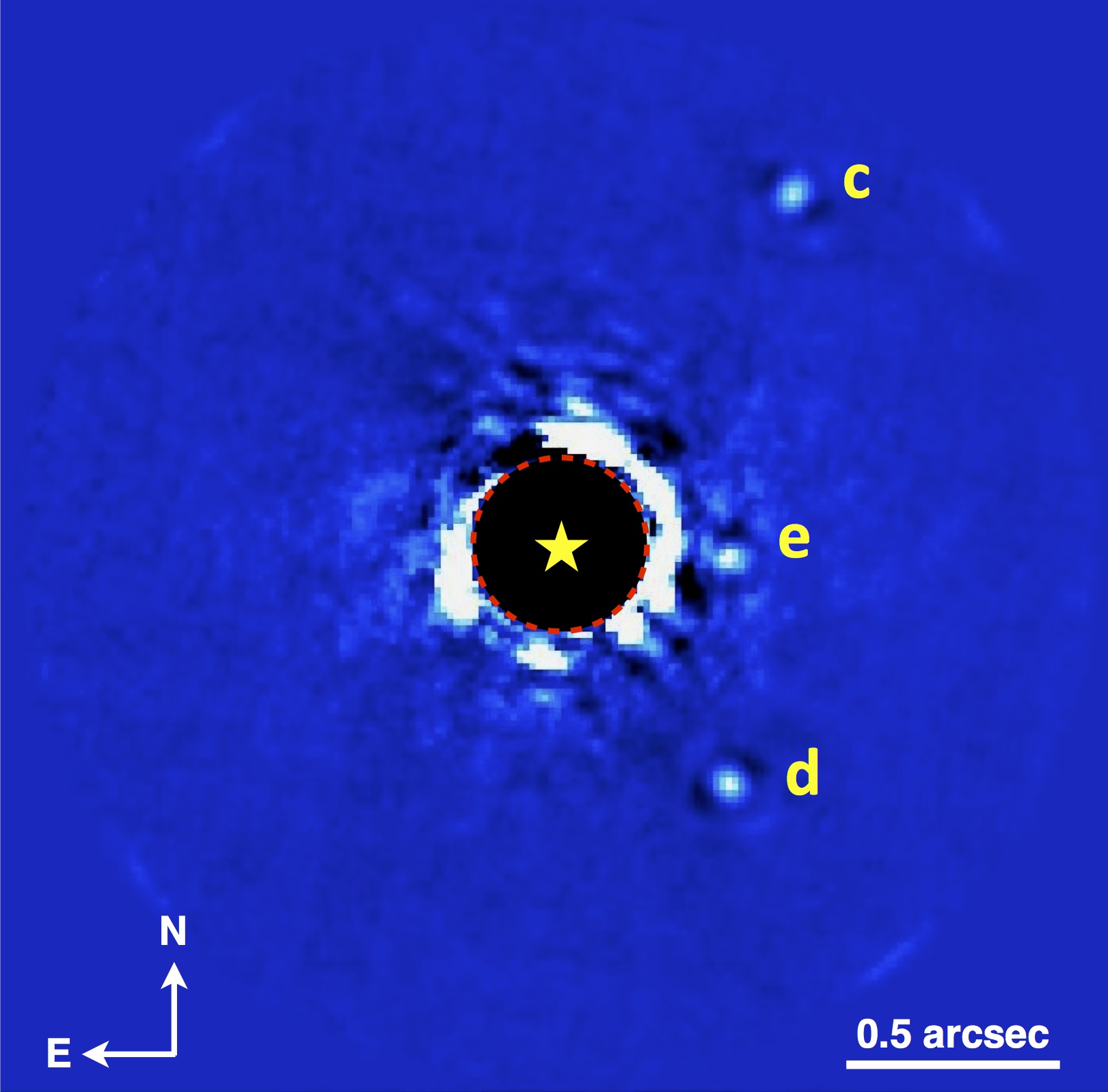

Astronomers trained GPI on HR 8799, a star found about 130 light-years from Earth that's known to host four planets. One stunning GPI image captured three of those planets, as well as the star, in the same frame. And GPI's measurements revealed significant differences in the light coming from two of the worlds, HR 8799c and HR 8799d — a surprise, since both planets are about the same size (roughly 20 percent larger than Jupiter) and appear to be the same color. [7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets]

"This was not expected at all based on the prior photometry," Marshall Perrin, of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said Tuesday during a news conference at the annual winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle.

Perrin and his colleagues aren't yet sure what the divergent spectra mean, but they have a theory.

"We believe that, most likely, what we're seeing is more uniform cloud cover on one of these planets versus more patchy cloud cover on the other, where you can see deeper into the atmospheric layers," Perrin said.

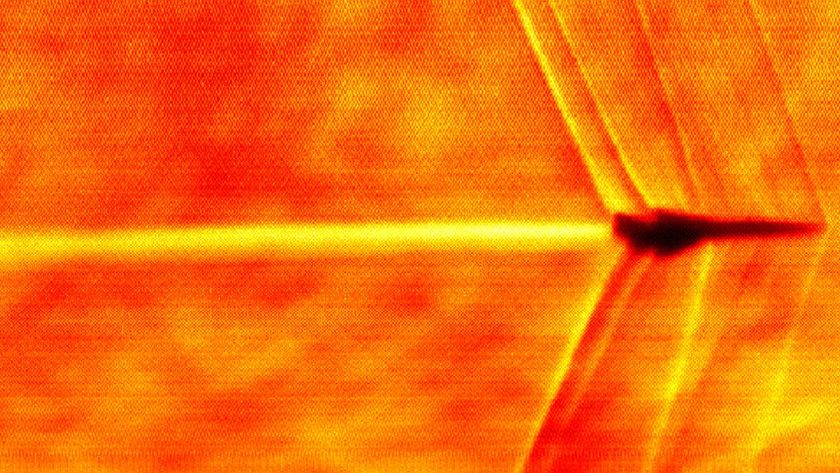

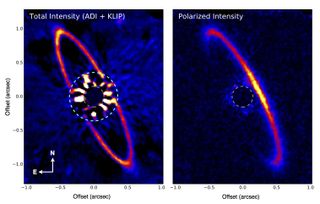

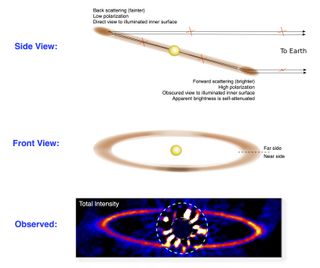

The Gemini Planet Imager has also studied the circumstellar disc surrouding HR 4796A, a young star that lies about 240 light-years from Earth. This ring of dust and planetary building blocks — which Perrin likened to a scaled-up version of our own solar system's Kuiper Belt — has been observed by other instruments, but GPI's keen eyes have revealed new insights.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For example, GPI's measurements show that HR 4796A's disc is partially opaque, suggesting that its dust is packed much more tightly than the dust at the outer reaches of Earth's solar system, Perrin said.

"In some ways, it's analogous to one of Saturn's rings — very narrow, slightly optically thick to get the brightness ratio right on the two sides of the disc," he said. "We're still thinking about the dynamics of this."

While GPI has been characterizing alien worlds and systems, it has not discovered any exoplanets yet. But that could change over the next few years, as astronomers plan to use the instrument to search 600 nearby stars for Jupiter-like planets.

GPI is designed to find and characterize such large gas giants. The instrument isn't sensitive enough to study small, rocky worlds — but its operations may help researchers develop future gear that can do just that, Perrin said.

"We're going to be opening up a lot of new discoveries, hopefully, over the next few years in terms of exoplanet imaging and, in the long run, taking these technologies and scaling them to future 30-meter telescopes, and perhaps large telescopes in space, to continue direct imaging and push down towards the Earth-like planet regime," he said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.