Update for March 6 at 10:09 a.m. EST: NASA's Dawn probe successfully entered orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres today at 7:39 a.m. EST (1339 GMT). Read the full story here - NASA Dawn Probe Enters Orbit Around Dwarf Planet Ceres, a Historic First

A NASA probe that takes four days to go from 0 to 60 mph is about to make space exploration history.

NASA's Dawn spacecraft is scheduled to arrive at the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, early Friday morning (March 6).

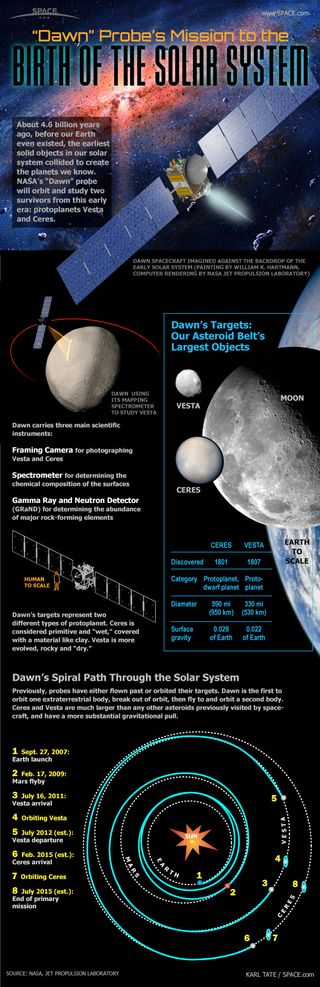

If all goes according to plan, Dawn will become the first probe ever to orbit a dwarf planet, as well as the first to circle two celestial bodies beyond the Earth-moon system. (Dawn, which launched in September 2007, studied the protoplanet Vesta, the asteroid belt's second-largest denizen, up close from July 2011 through September 2012.) [Amazing Photos of Dwarf Planet Ceres]

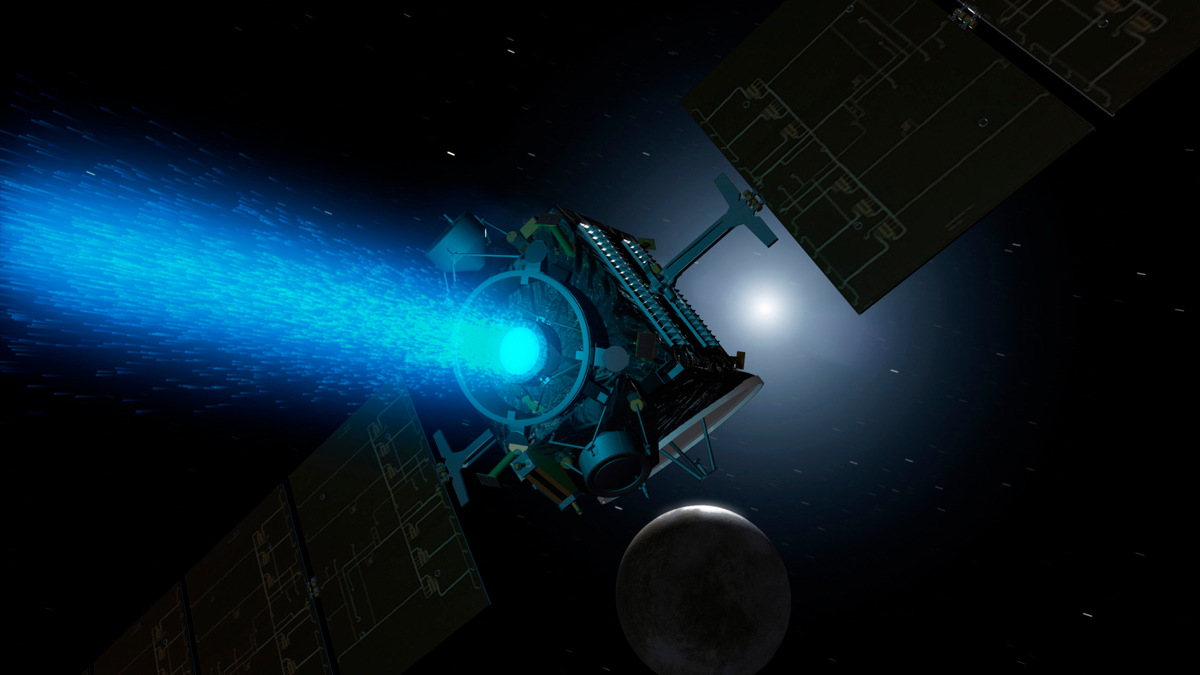

The $473 million Dawn mission's unprecedented deep-space feats are enabled by its innovative ion propulsion system, which is about 10 times more efficient than traditional chemical thrusters. Dawn's engines ionize xenon atoms and then accelerate the ions out the back of the spacecraft using a large voltage.

This process generates tiny amounts of thrust — the equivalent of a piece of paper pushing on your hand. But that thrust adds up over time, allowing the Dawn spacecraft to achieve tremendous velocities.

"Ion propusion enables us to do things, and go places, that would be either extremely expensive or completely impossible to do," Dawn project manager Robert Mase, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said during a news conference Monday (March 2). "Dawn really capitalizes on this innovative technology to deliver big science on a small budget."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ion propulsion has also allowed Dawn's handlers to craft a slow, gentle approach to Ceres that should result in a low-stress orbital arrival. There will be no critical, make-or-break orbital-insertion burns, such as the ones that typically deliver orbiters to Mars and other deep-space destinations.

"We just slip right in, and there's no moment of truth or anything like that," Dawn principal investigator Christopher Russell of UCLA told Space.com. "So it's boring but safe."

Dawn will continue to demonstrate the advantages of ion engines after it reaches Ceres, Russell added.

"When we get into orbit, we can optimize our trajectory," he said. "If we want to be in a particular local time sector, or we want to be at a particular altitude or particular sun angle — things of that nature — we can go there and, with the ion propulsion engine, tailor that orbit very easily."

Dawn isn't the first interplanetary mission to employ ion propulsion; NASA's Deep Space 1 probe and Japan's asteroid-sampling Hayabusa spacecraft also used ion thrusters. (Those probes launched in 1998 and 2003, respectively.) But Dawn is showing just what the technology is capable of, and that will be a big part of the mission's legacy, Russell said.

"When other people appreciate what Dawn did [with ion propulsion], we will doing a lot more of this," he said. "It takes a little bit of extra time, but it's safer and cheaper, and that's important."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.