In Search for Alien Life, Follow the Water

NEW YORK - The search for life beyond Earth homes in on water, whose abundance throughout the solar system is becoming increasingly clear to scientists.

Water is a polar molecule and a solvent, two properties that are important for certain chemical reactions critical to life, said NASA chief scientist Ellen Stofan.

"We think water is key to life as we know it," Stofan said Tuesday (April 28) during the Asimov Memorial Debate, an annual event at New York's American Museum of Natural History that was moderated by Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the museum's Hayden Planetarium. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

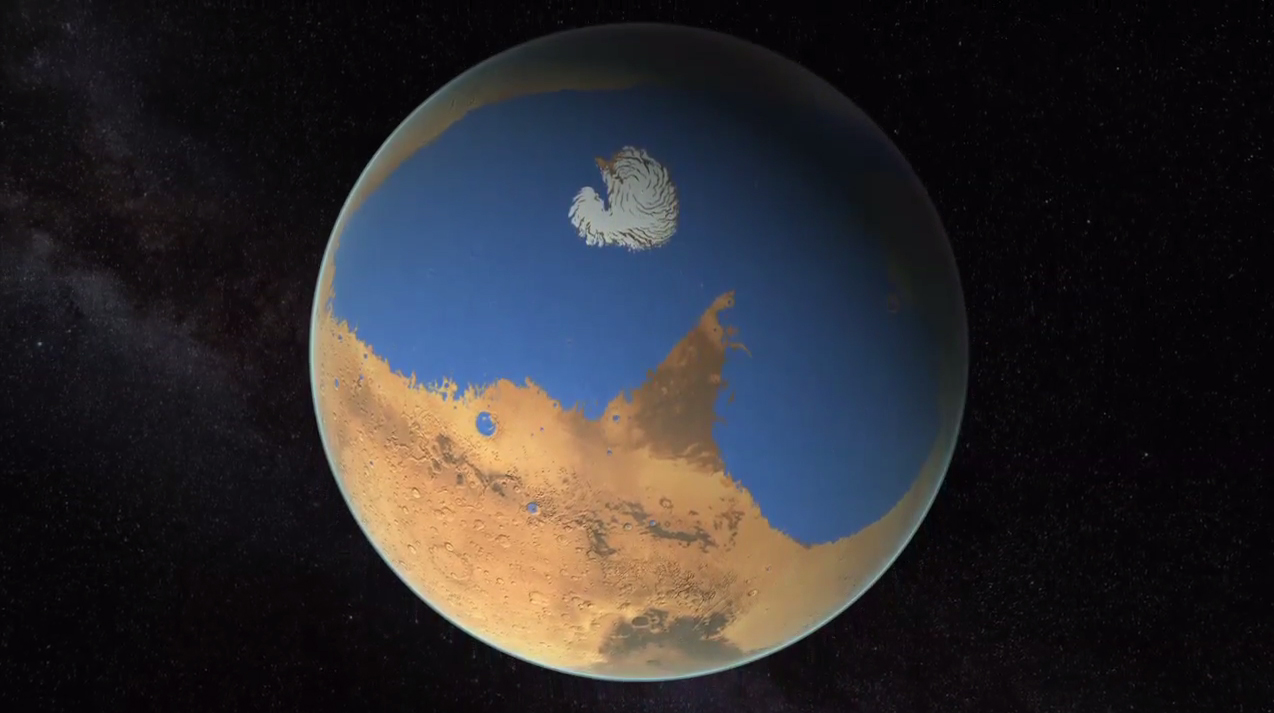

And Earth is certainly not the only world with ample stores of the stuff. Jupiter's moon Europa is covered with a sheet of ice that very likely sits on top of a global ocean, and Saturn's moon Enceladus shows evidence of subsurface water as well. Mars, meanwhile, was once a relatively warm and wet world that apparently harbored large amounts of liquid water in the ancient past for a long period of time — perhaps up to a billion years, Stofan said.

Astrobiologists regard Europa and Enceladus as viable candidates to host alien life today. While researchers might not find life on Mars now, it might have existed there once, Stofan said.

"Many of us in the scientific community have a pretty strong belief, based on science, that at some point life was likely to have evolved on the surface of Mars," Stofan said. "The hard part is going to be finding it."

Any Martian life that is found is likely to be microbes, not "little green men," she added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Here on Earth

Participating along with Stofan and Tyson in Tuesday night's event — which was called, appropriately enough, "Water, Water" — were Kathryn Sullivan, Administrator at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); retired US Air Force Gen. Charles Wald; hydrologist Tess Russo; and astronomer Heidi Hammel, an expert on comets and other water-bearing bodies in the solar system.

The discussion did not focus solely on the search for alien life. In fact, much of it was about a looming set of crises that fresh water supplies are facing on Earth, and the connection with NASA and space science. Sullivan noted that NOAA and NASA work closely together; NOAA operates a satellite fleet that monitors weather, climate and land use.

Russo said satellite-based studies of water use can and do help farmers understand how to use water more efficiently. Some 2.4 percent of all the water on Earth is fresh water, and humans can use only a fraction of that, about 0.4 percent of the total. Of that, about 70-90 percent is used for agriculture.

Tyson posited that the plans to settle humans on Mars can be connected with how we use water on Earth, and that technologies for recycling might have Earthbound applications. [The Boldest Mars Missions in History]

Stofan agreed that recycling water is key. On the International Space Station, some 85 percent of the water is recycled. To get to Mars, that percentage will have to be even higher. And water, she added, isn't just for drinking, but for rocket fuel as well.

There isn't any liquid water on Mars' surface, and getting at the stuff might not be easy. "Mars is not a 'live off the land' kind of place," Stofan said. The likely route will be to pre-position some kind of water extraction apparatus on Mars before sending humans.

On other worlds, though, water is even harder to access. On the moon, much of it is locked in clathrates, said Hammel. Clathrates are compounds in which water molecules are trapped inside molecular lattices. Getting the water out is not easy. "You have to go through a lot of material," she said.

Water crises

As to water crises on Earth, technology – even from NASA -- might not be enough to solve them. "One of the difficulties is taking a NASA thing and scaling it up," Hammel said.

As it is, humans use a lot of water, and not always sensibly.

"In Las Vegas, per capita water use is twice as much as in New York," Sullivan said. "But it rains 10 times as much here [in New York]." On top of that, 90 percent of the water in Nevada is used for agriculture. Such imbalances are common. It takes three times more water to produce a plastic water bottle than the bottle contains, she added.

Russo said humanity is draining aquifers much faster than they recharge. "We are pumping water that recharged in a previous ice age," she said. "The time it takes water to go back to the aquifer is much longer than it takes to pump it. "

From a national security perspective, depleting water has serious implications, Wald said. "In Gaza, water is of the essence. They are using so much that in two years they won't have any more." Meanwhile the Ethiopian government has plans for a huge dam on the Nile, which will impact the countries downstream. "Water wars will be exacerbated."

Even within the United States, water conflicts are becoming more serious, as states fight via the courts over water resources. States such as California grow a large portion of the nation's food. "The California water problem is all of our problem. We're in a crisis right now," Stofan said.

Sullivan noted that a lot of water that could be used for drinking is simply wasted watering lawns — and it ends up being drained right to the ocean from treatment plants. On top of that, water is cheap, so there's not much incentive to cut back use. And more efficient usage might be the only option. Desalination is energy intensive and generates waste.

"When you suck salt out of seawater, what you have left is thick brine," Sullivan said. "That's your waste product."

The panelists generally were not optimistic that anything but a major crisis would change American habits. At the same time, they had hope that future engineers and scientists could help solve some of the problems. And space science, Hammel said, might be key to that.

"We once polled a bunch of engineers," Hammel said. "They didn't talk about desalination; they said what inspired them was space… Somewhere there's a little girl who is interested in science and went to her local library. She didn't get a book on desalination, she took out a book on black holes."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.