This Galaxy Far, Far Away Is the Farthest One Yet Found

A galaxy far, far away — farther, in fact, than any other known galaxy — has been measured by astronomers.

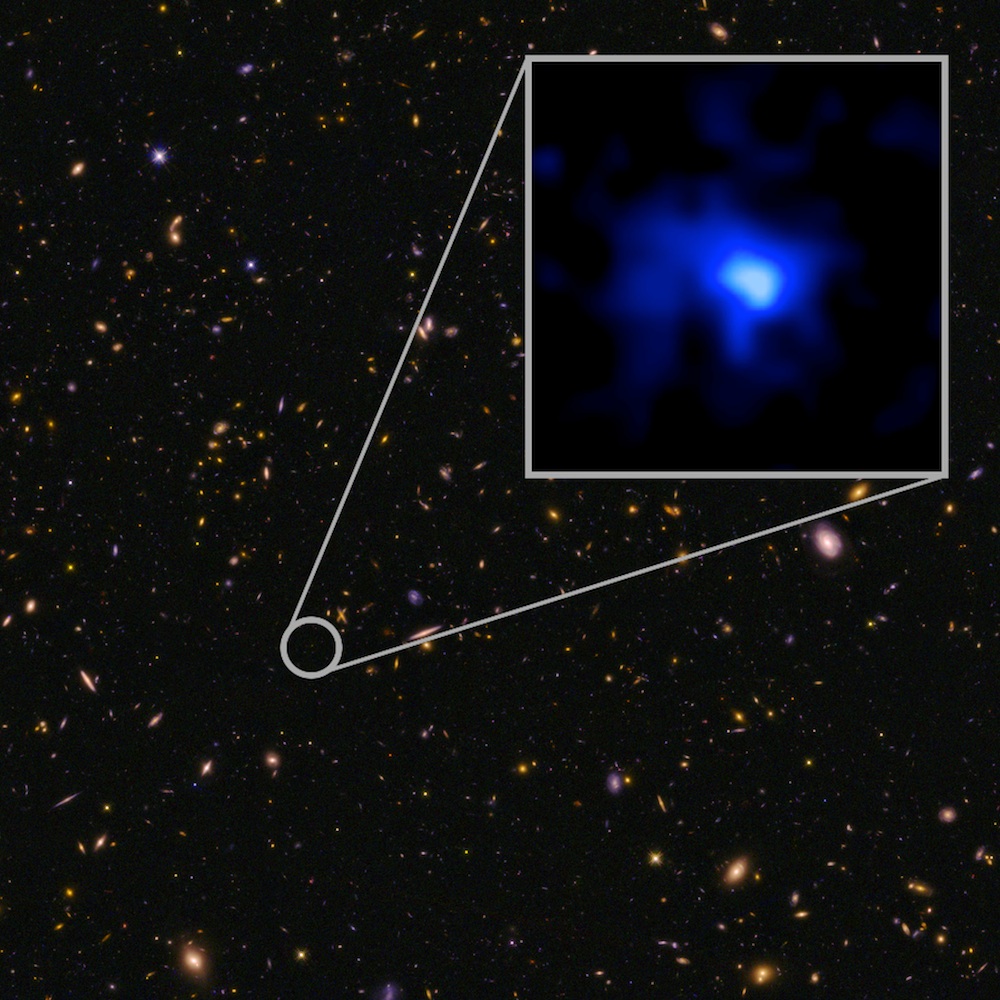

The galaxy EGS-zs8-1 lies 13.1 billion light-years from Earth, the largest distance ever measured between Earth and another galaxy.

The universe is thought to be about 13.8 billion years old, so galaxy EGS-zs8-1 is also one of the earliest galaxies to form in the cosmos. Further studies could provide a glimpse at how these early galaxies helped produce the heavy elements that are essential for building the diversity of life and landscapes we see on Earth today. [The Greatest Galaxy Images Ever Taken]

EGS-zs8-1 is one of the brightest objects observed in this region, which is around 13 billion light-years from Earth. The authors of the new research say other galaxies likely lie at similar distances or even further from Earth, but they are too faint for scientists to measure their exact distance.

"We have a lot of sources that we can see with Hubble that are probably farther way" than EGS-zs8-1, said Pascal Oesch, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale and lead author of the new study. "But we cannot measure their exact distance yet."

To measure the separation between Earth and a far-off cosmic object, astronomers often look at how quickly those objects are moving away from Earth. The universe is expanding; space itself is growing like a balloon or a loaf of bread in the oven. Objects in the universe thus move away from each other, like raisins in the bread dough.

As these objects move away from Earth, the light they emit becomes shifted. The more far-flung an object is, the faster it appears to move away from Earth, and the more the light is shifted. So, by measuring the degree of shifting — known as "redshift" — astronomers can also measure distance. A higher redshift equals a larger distance, and galaxy EGS-zs8-1 has the highest redshift ever measured, according to the new research (the previous record holder has a redshift that is only slightly smaller).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

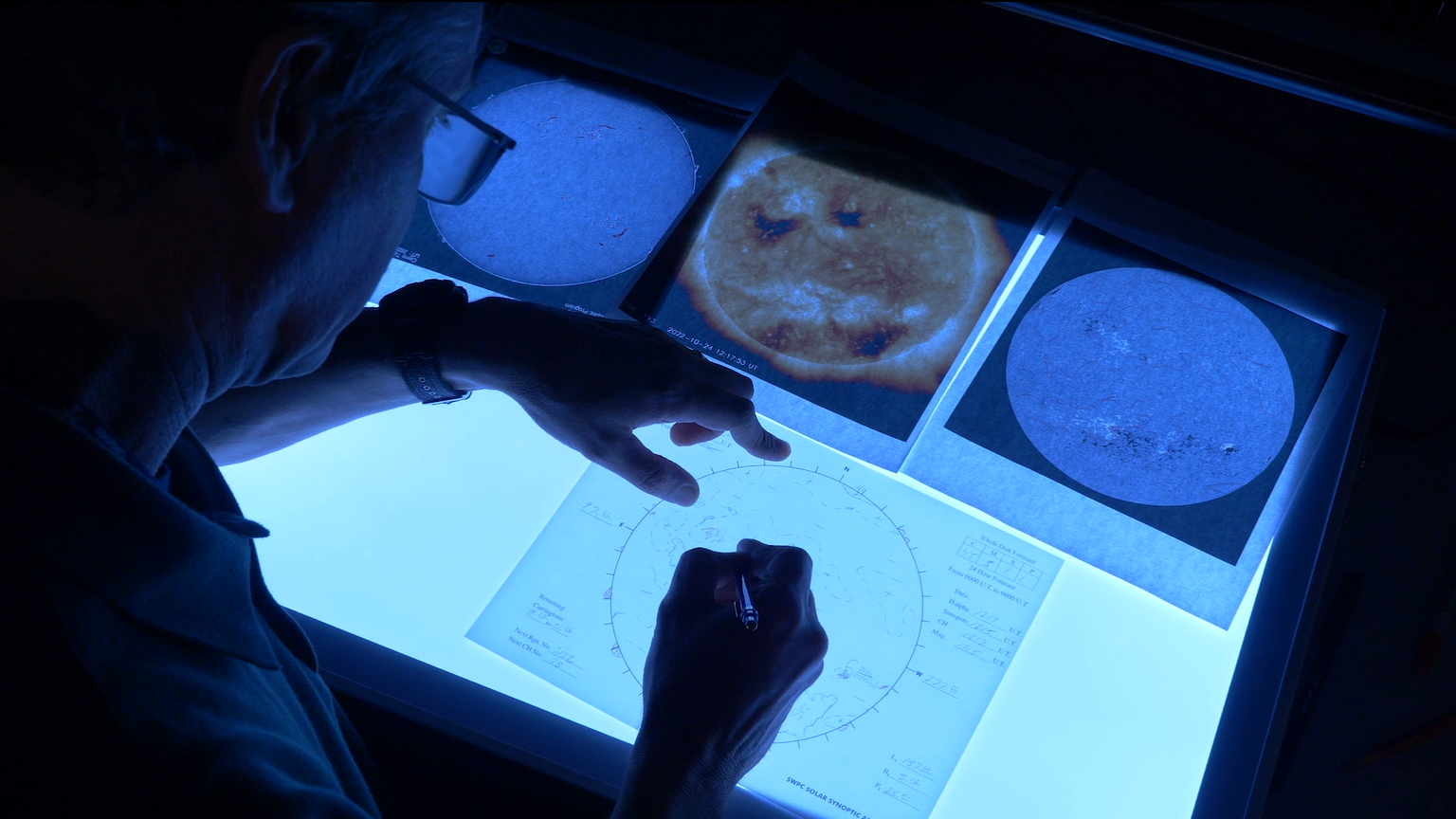

Galaxy EGS-zs8-1 was originally identified by the Hubble Space Telescope and the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope, and stood out because of the unique colors it emitted. The new research used observations conducted with the MOSFIRE instrument on the W.M. Keck Observatory's 10-meter (33 feet) telescope in Hawaii.

The light from EGS has traveled a distance of 13.1 billion light-years, so the light shows EGS-zs8-1 as it was 13.1 billion years ago. At that time, the universe was only about 670 million years old, or about 5 percent its current age of about 13.8 billion years, according to a statement from Yale. The first stars began forming about 200 million to 300 million years after the Big Bang, according to Oesch.

By combining observations from Keck, Spitzer and Hubble, the researchers say they can estimate that the stars in EGS-zs8-1 are "between 100 [million] and 300 million years old." But Oesch said it is difficult to know how old EGS-zs8-1 is compared to other galaxies at a similar distance from Earth. It is, however, one of the oldest galaxies yet measured.

The new observations also show that EGS-zs8-1 is forming stars 80 times faster than the Milky Way. In addition, the still-growing galaxy has "already built more than 15 percent of the mass of our own Milky Way today," Oesch said in a statement from Yale University.

The unique colors observed in EGS and other early galaxies by the Spitzer Space Telescope present questions about what took place in these primeval environments. According to the statement, these colors could have been caused by the rapid formation of massive, young stars that interacted with the primordial gas in these galaxies. Oesch said further study of the galaxy could reveal the types and amounts of heavy elements that formed there.

"By looking at different galaxies as a function of time, we can reconstruct the build-up of the heavy elements that we see around us today and that we're all made of," Oesch said. In addition, the new observations provide "an indication of how the stars were forming at these extreme distances, and they seem to be forming differently than the local universe. Every discovery opens up a whole new set of questions."

The research appeared online today (May 5) in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters. A pre-print of the paper can be found online. .

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter