Saturn's icy moon Enceladus is looking better and better as a potential abode for alien life.

Chemical reactions that free up energy that could potentially support a biosphere have occurred — and perhaps still are occurring — deep within Enceladus' salty subsurface ocean, a new study suggests.

This determination comes less than two months after a different research team announced that active hydrothermal vents likely exist on Enceladus' seafloor, suggesting that conditions there could be similar to those that gave rise to some of the first lifeforms on Earth. [Photos: Enceladus, Saturn's Cold, Bright Moon]

A salty ocean

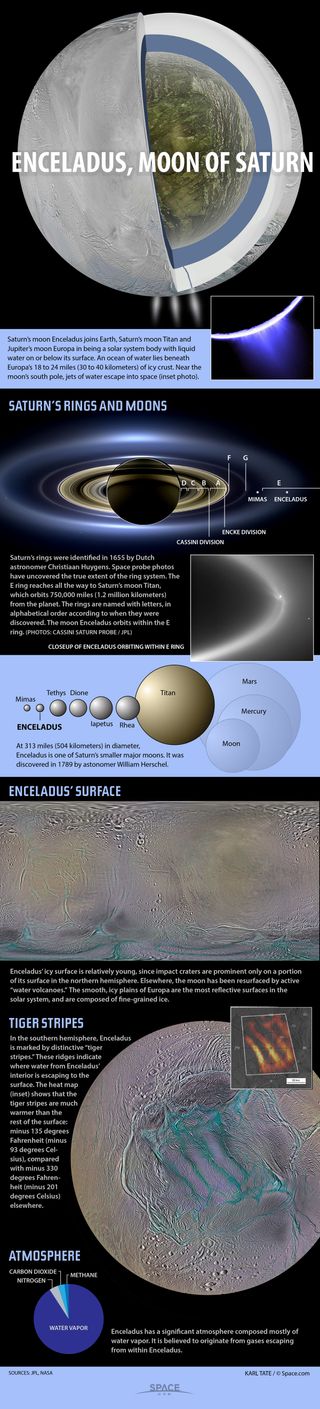

Astrobiologists regard the 314-mile-wide (505 kilometers) Enceladus as one of the solar system's best bets to host life beyond Earth.

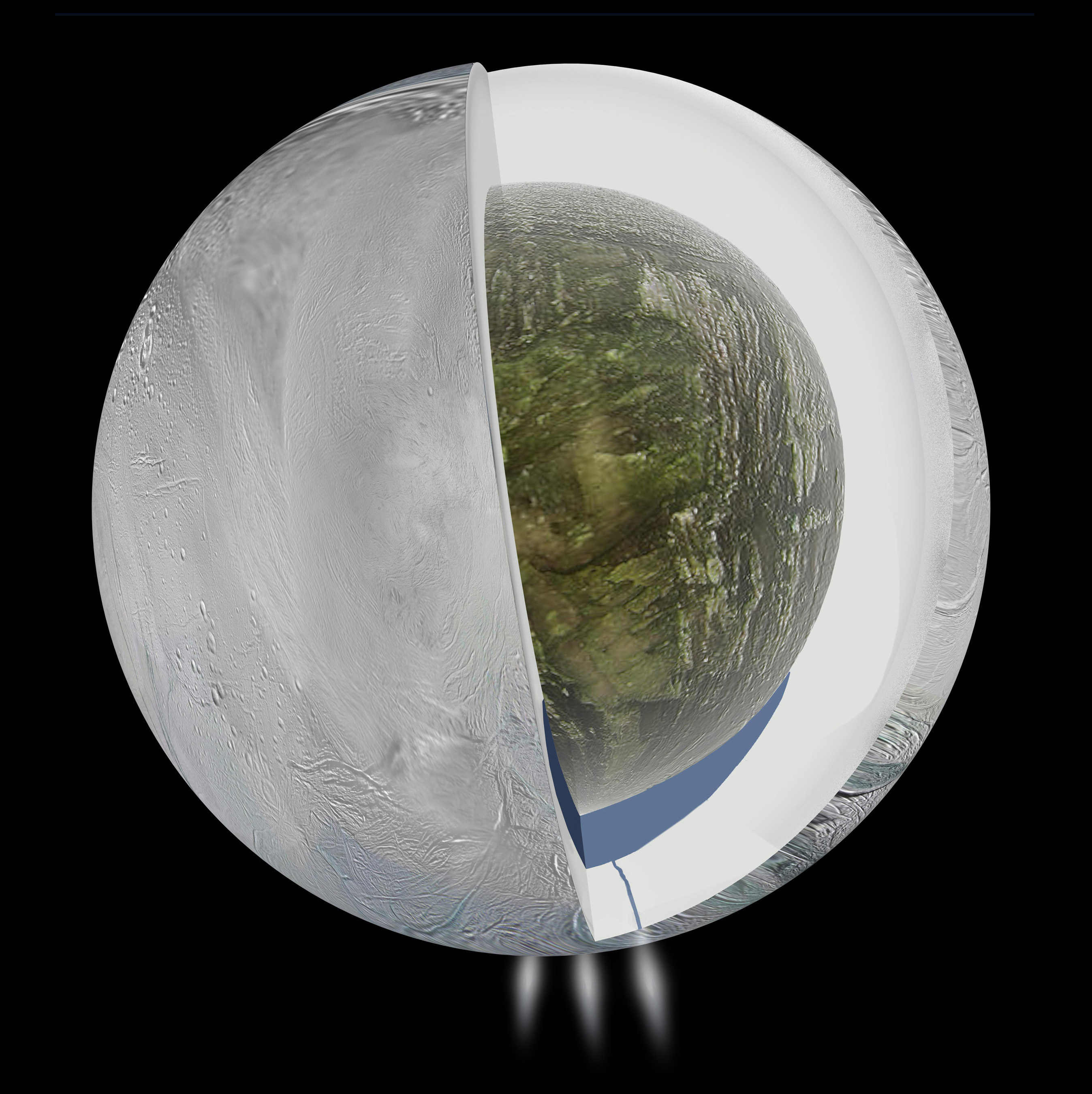

The satellite is covered by an icy shell, but it's geologically quite active, as evidenced by the powerful geysers that blast continuously from its south polar region. These plumes contain significant amounts of water, which scientists think originates from a subsurface ocean.

Previous studies have suggested that this ocean is in contact with Enceladus' rocky mantle, making possible all sorts of interesting chemical reactions. The new paper, published Wednesday (May 6) in the journal Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, further supports that notion.

The researchers studied mass-spectrometry measurements of the gases and ice grains in Enceladus' plumes made by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which has been orbiting Saturn since 2004. The team used this information to develop a model that estimates the saltiness and pH of Enceladus' plumes, and, by extension, the moon's underground ocean.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists determined that the ocean is likely salty and quite basic, with a pH of 11 or 12 — roughly equivalent to that of ammonia-based glass-cleaning solutions, but still within the tolerance range of some organisms on Earth. (The pH scale runs from 0 to 14. Seven is neutral; anything higher is basic, and anything lower is acidic.)

Enceladus' subsurface sea contains dissolved sodium chloride (NaCl) — run-of-the-mill table salt — just as Earth's oceans do, researchers said. But it's full of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), which is also known as washing soda or soda ash, as well.

So this alien water body is probably more similar to terrestrial "soda lakes," such as Mono Lake in California, than it is to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, study team members said.

An energy source in the dark depths

Such inferences shouldn't dishearten astrobiologists; a variety of lifeforms thrive in Mono Lake, including brine shrimp and many different types of microbe. And the new study provides other reasons to be optimistic about Enceladus' life-hosting potential, researchers said.

For example, the team's model suggests that the subsurface ocean's high pH is generated by a process called serpentization, in which certain kinds of metallic rocks from Enceladus' upper mantle are transformed into new minerals (including serpentine, hence the name) via interactions with water.

In addition to raising pH, serpentization results in the production of molecular hydrogen (H2) — a potential source of chemical energy for any lifeforms that may exist in the underground sea, researchers said.

"Molecular hydrogen can both drive the formation of organic compounds like amino acids that may lead to the origin of life, and serve as food for microbial life such as methane-producing organisms," study lead author Christopher Glein, of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, said in a statement.

"As such, serpentinization provides a link between geological processes and biological processes," he added. "The discovery of serpentinization makes Enceladus an even more promising candidate for a separate genesis of life."

Sunlight probably doesn't flow through Enceladus' underground sea, but any microbes that exist there may thus have access to two different sources metabolism-supporting energy sources — molecular hydrogen and the heat provided by hydrothermal vents.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.