NASA's Europa spacecraft will use nine scientific instruments to assess the icy, ocean-harboring Jupiter moon's ability to support life, space agency officials announced today (May 26).

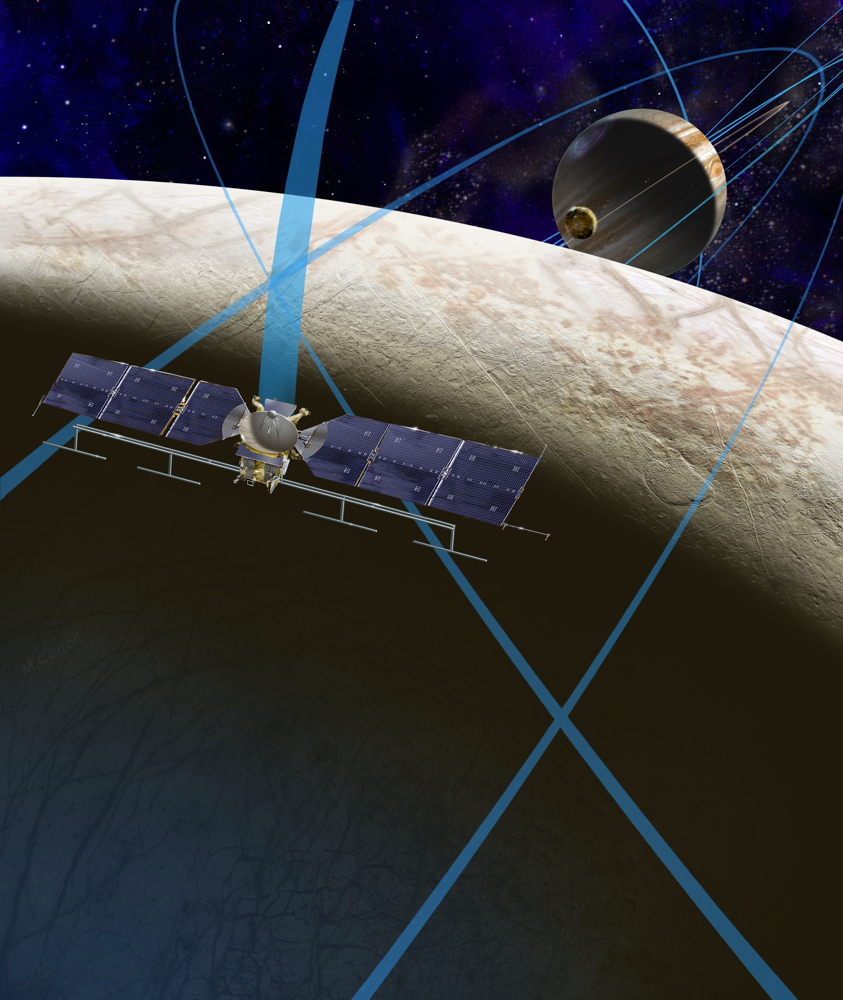

The Europa probe — which is scheduled to launch in the early to mid-2020s — will carry supersharp cameras, a heat detector, ice-penetrating radar and a variety of other gear that will shed light on the satellite's surface composition and the nature of its salty subsurface sea, among other things, NASA officials said.

The newly announced scientific payload "will help us take great strides forward in understanding the habitability of Europa," Curt Niebur, Europa program scientist at NASA's Washington headquarters, said during a news conference today. [Europa May Harbor Simple Life-Forms (Video)]

Haven for life?

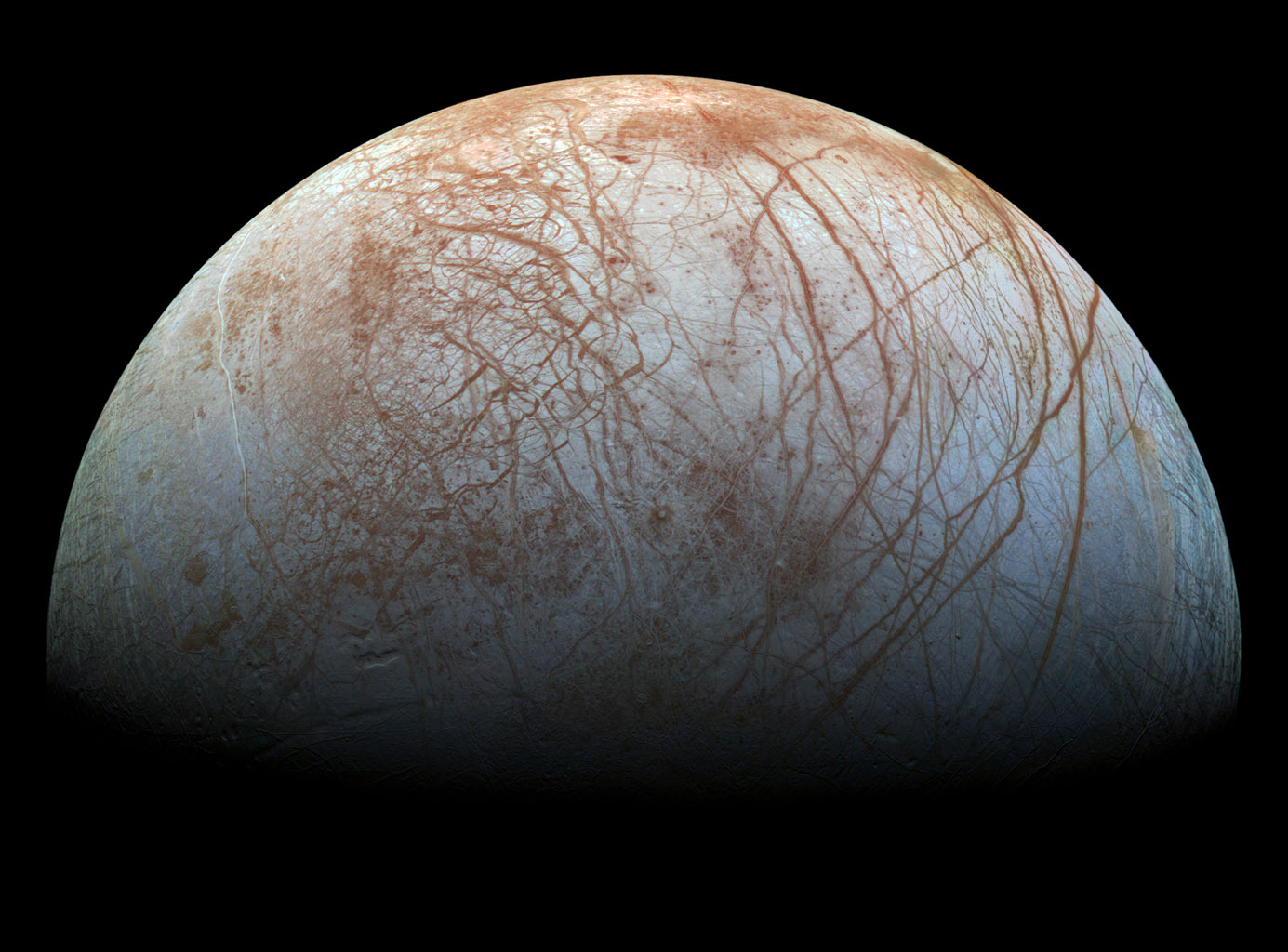

Astrobiologists regard the 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 kilometers) Europa as one of the solar system's best bets to host extraterrestrial life.

Europa possesses a salty ocean beneath its ice shell, and this sea is apparently in contact with the moon's rocky mantle, making possible a number of complex chemical reactions, scientists say. In addition, scientists think that Europa's seafloor also features hydrothermal vents, providing a potential energy source for life-forms, if any exist in the dark depths. (Life thrives at Earth's undersea vents, and some researchers think these environments gave rise to the planet's first organisms.)

Most of what scientists know about Europa is based on data gathered by NASA's Galileo mission, which orbited Jupiter in the 1990s and early 2000s and made about a dozen flybys of Europa during that time.

The new mission, which will cost roughly $2 billion, aims to build upon and increase that knowledge significantly, specifically investigating the icy world's life-hosting potential. The current plan calls for sending a solar-powered spacecraft into orbit around Jupiter; from there, the probe would make about 45 flybys of Europa over the course of two and a half years or so.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We find that multiple flybys can allow us to get a complete picture of Europa," said Jim Green, head of NASA's Planetary Science division.

In July 2014, NASA asked researchers around the world to propose scientific instruments for the Europa mission. The space agency received 33 submissions and has now selected nine to go on the spacecraft, Niebur said today. [Europa and Its Ocean (Video)]

Taking Europa's measure

The Europa flyby probe's imaging system will consist of one wide-angle camera and one narrow-angle one, Niebur said. These two cameras will map almost 90 percent of Europa's surface down to a resolution of 164 feet (50 meters), and will image parts of the moon 100 times more sharply than that.

Galileo, by contrast, imaged just 10 percent of Europa's surface down to a resolution of 650 feet (200 m), Niebur said.

"If we've seen such amazing things on only 10 percent of the surface, it's hard to even imagine the amazing things we'll see when we look at the rest of Europa at even better resolution," Niebur said.

Two other instruments — a magnetometer and a magnetic sounder — will work together to determine the thickness of Europa's ice shell and the depth and salinity of its ocean. The ice-penetrating radar equipment will provide even more detail about the moon's icy crust.

The probe will also carry a heat detector to pinpoint active sites on Europa — for example, places where plumes of water vapor may be erupting into space.

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope spotted signs of such geysers erupting in 2012, but further searches have not yet confirmed their existence. The Europa spacecraft will carry a plume-hunting spectrograph, to both find and chacterize these elusive features.

Furthermore, an infrared spectrometer will allow the probe to map out the composition of Europa's surface. Scientists are especially keen to know exactly what makes up the reddish-brown "gunk" that coats large fractures on the moon, since the stuff likely erupts onto the surface from the ocean below.

"If we can determine what that brown gunk is, we can then understand what is in the water — what is in the oceans of Europa — and that is an incredibly important question to answer if we're trying to figure out if this place is habitable," Niebur said.

The final two instruments — a mass spectrometer and a dust analyzer — will characterize gases and small solid particles that get blasted off Europa's surface into space, allowing mission scientists to study the moon's surface composition without touching down.

No life-detection gear

The Europa flyby mission is dedicated to probing the moon's habitability, not actively seeking out signs of life.

"Building a life detecor is incredibly difficult," Niebur said. "We're not even sure how to go about building it yet. But it's something that has received renewed interest and vigor lately because of the Europa mission, so that's something that we're going to be poking into a lot more aggressively in the near future."

Many astrobiologists would love to get a probe down on Europa's surface — and, ideally, into the underground ocean. The data gathered by the flyby spacecraft could help pave the way for such an ambitious effort, NASA officials said.

"It'd be great to think that the results from this particular mission would lead, in the next decade, to some new and exciting concepts about potentially getting underneath the ice shell," Green said.

More information is needed to determine if Europa "can be penetrated in a way to be able to get under the ice shell," he added. "But that's, indeed, in the distant future."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.