US-China Cooperation in Space: Is It Possible, and What's in Store?

There's a growing debate over whether China and the Unites States should cooperate in space, and the dialogue now appears to focus on how to create an "open-door" policy in orbit for Chinese astronauts to make trips to the International Space Station (ISS).

Discussion between the two space powers has reached the White House, but progress seems stymied by Washington, D.C., politics. Specifically at question is how to handle a 2011 decree by the U.S. Congress that banned NASA from engaging in bilateral agreements and coordination with China regarding space.

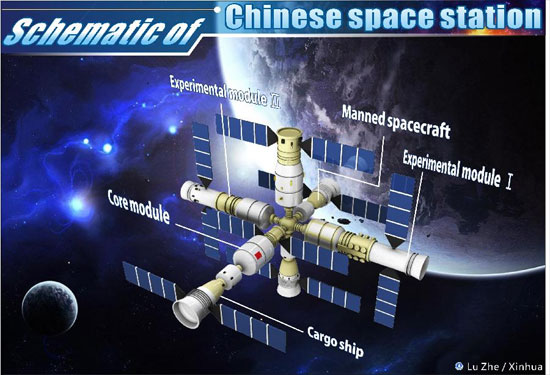

Meanwhile, the Chinese space program is pressing forward with its own "long march" into space, with the goal of establishing its own space station in the 2020s. Space.com asked several space policy experts what the future holds for U.S.-China collaboration in space. [China in Space: Latest News and Missions]

Presidential leadership

It will take presidential leadership to get started on enhanced U.S.-Chinese space cooperation, said John Logsdon, professor emeritus of political science and international affairs at The George Washington University's Space Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.

"The first step is the White House working with congressional leadership to get current, unwise restrictions on such cooperation revoked," Logsdon told Space.com. "Then, the United States can invite China to work together with the United States and other spacefaring countries on a wide variety of space activities and, most dramatically, human spaceflight."

Logsdon said the U.S.-Soviet Apollo-Soyuz docking and "handshake in space" back in 1975 serves as a history lesson.

"A similar initiative bringing the United States and China together in orbit would be a powerful indicator of the intent of the two 21st century superpowers to work together on Earth as well as in space," Logsdon said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While it is impressive that China has become the third country to launch its citizens into orbit, the current state of the Chinese human spaceflight program is about equivalent to the U.S. program in the Gemini era, 50 years ago, Logsdon noted.

"China has much more to learn from the United States in human spaceflight than the converse," Logsdon said. "From the U.S. perspective, the main reason to engage in space cooperation with China is political, not technical."

Complicated relationship

The U.S. and China have a complex relationship, said Marcia Smith, a space policy analyst and editor of SpacePolicyOnline.com. "It is not like the U.S.-Soviet Cold War rivalry that was driven by military and ideological competition."

Today, the U.S.-Chinese situation has those elements, Smith told Space.com, "but our mutually dependent trade relationship makes it a whole different kettle of fish."

Smith pointed out that, as far as space cooperation goes, the United States had very low-level agreements with the Soviets from the early 1960s on sharing biomedical data. During the Richard Nixon administration, the doors were flung open to what became the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), only to close again under then-President Jimmy Carter after the Soviets invaded, ironically, Afghanistan. Even during the strained years of the Ronald Reagan administration, small programs — again, mostly in the biomedical area — were allowed to continue, Smith said.

"But the bold cooperation on human spaceflight — the equivalent of inviting China to join the ISS partnership — waited for regime change," Smith told Space.com "It is U.S.-Russian cooperation, not U.S.-Soviet. Perhaps when there is regime change in China, we will see the same kinds of possibilities emerge."

Until then, "one would hope that low-level cooperation, akin to U.S.-Soviet space cooperation in the 1960s or 1980s, might be possible," Smith added. The law does allow multilateral, not bilateral, cooperation, she said. "The door is not completely shut."

A U.S.-China space race?

"It is in the interest of U.S. national security to engage China in space," said Joan Johnson-Freese, a professor of national security affairs at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island.

Johnson-Freese noted that her views do not necessarily represent those of the Naval War College, the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

"The United States has unnecessarily created the perception of a space race between the U.S. and China, and that the U.S. is losing, by its unwillingness to be inclusive in ISS space partnerships," Johnson-Freese said.

Refusing Chinese participation in the International Space Station, at least in part, has spurred China to build its own station, Johnson-Freese said, "which could well be the de facto international space station when the U.S.-led ISS is deorbited." [China's Space Station Plans in Photos]

Cooperation stonewalled

Apollo-Soyuz demonstrated that space can be a venue to build cooperation and trust during difficult political times, when they are most needed, and without dangerous technology transferal, Johnson-Freese said. "However, that demonstration has gone unheeded regarding China," she noted.

Johnson-Freese said the reasoning given by those who have stonewalled cooperation in space with the Chinese "often has little to do with space or national security." Rather, "space is merely a token for complaints about China in other areas, such as human rights," she said.

Other countries are eager to work with China in space, Johnson-Freese said, and "the U.S. merely appears petulant" in its refusal to engage in any meaningful way with China in space.

Europe and China

The European Space Agency (ESA) and China have blueprinted a work plan, said Karl Bergquist, who's in charge of relations with China within the ESA international relations department in Paris. [How China's First Space Station Will Work (Infographic)]

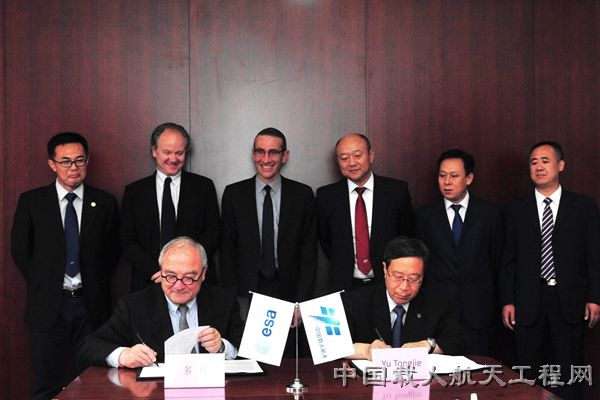

ESA and the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) signed a framework agreement in December 2014, Bergquist said.

Since then, the two agencies have established three working groups: space experiments and utilization; astronaut selection, training and flight; and space infrastructure to analyze and propose concrete cooperation areas of mutual interest, Bergquist told Space.com.

Outgoing ESA Director Jean-Jacques Dordain and CMSA Director Yu Tongjie met May 27 to continue strategic cooperation on long-term objectives and implementation steps.

"As you can see, we are still in the early phases of the cooperation between ESA and CMSA," Bergquist said, "but the idea is to identify a concrete cooperation plan which then could be submitted for approval to the ESA member states."

Escape route

Logsdon said ESA, or even the Russian space agency, could serve as somewhat of a "middleman" to facilitate Chinese access to the International Space Station.

"If China were to fly its Shenzhou spacecraft to the space station, it would dock to the Russian port … and Putin's Russia has been making friendly noises towards China," Logsdon said.

Dordain has been a strong advocate for incorporating China into mainstream spaceflight activities, Logsdon said. Dordain's term of office ends June 30. The incoming leader of ESA is Johann-Dietrich Wörner, who is currently chairman of the German Aerospace Center's executive board.

"It is not clear either how much leverage Europe would have on this issue or whether Dordain's successor will share this view, but with U.S. backing, Europe could serve as an American surrogate," Logsdon said.

Logsdon said it is worth remembering that the U.S. congressional prohibition regarding China is on bilateral U.S.-Chinese cooperation.

"Starting the cooperation on the multilateral International Space Station may offer an escape route from current limitations," Logsdon said.

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is former director of research for the National Commission on Space and is co-author of Buzz Aldrin's 2013 book "Mission to Mars – My Vision for Space Exploration," published by National Geographic, with a new updated paperback version released in May. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.