Ice Lab Plays It Cool for Pluto Flyby

Researchers in an Arizona ice lab spend long hours making crystal-clear ice from mixes of methane, nitrogen and even carbon monoxide — and now, with data from the New Horizons mission to Pluto arriving soon, the lab's time has come.

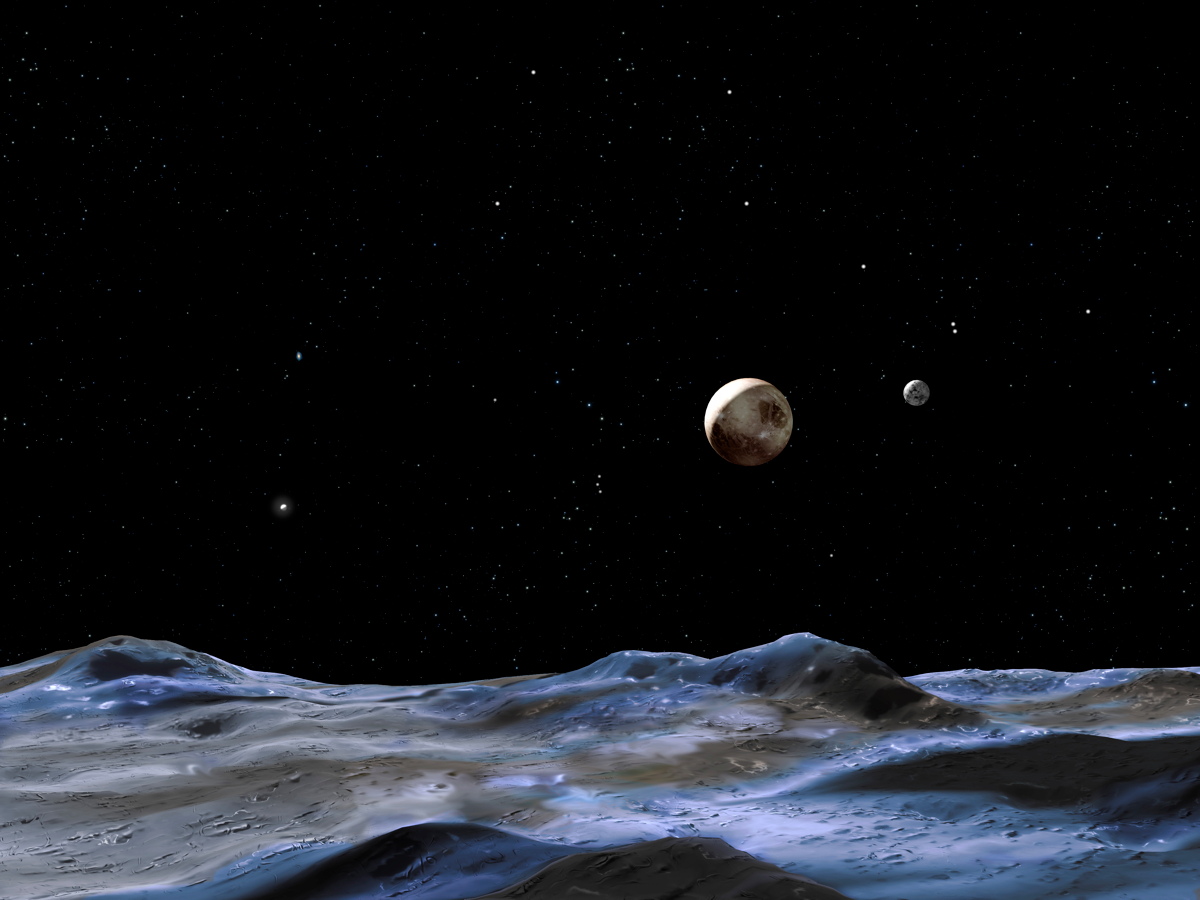

The surface of Pluto is likely covered in a coarse mixture of ices that don't resemble anything found naturally on Earth. The bitter cold on icy dwarf planets like Pluto and Eris, discovered in 2005, crystallizes blends of substances that on Earth occur more commonly as gases: mainly nitrogen, with a heaping dose of methane and a smattering of other molecules mixing things up.

To understand the composition of a planet like Pluto from a distance, researchers measure the wavelengths of light that bounce off of the planet's surface, by telescope or (when possible) much closer up, by spacecraft. Those distinctive wavelengths create a sort of fingerprint for different substances, and by comparing the fingerprints to a database of ice measurements back home, researchers hope to figure out the molecular compositions, temperatures and phases of matter covering Pluto's surface. [The Pluto Flyby: Our Complete Coverage]

The ice lab at Northern Arizona University has been focusing on creating and measuring ices with different proportions of methane and nitrogen in preparation for the incoming Pluto data. They've also begun to incorporate some of the other molecules observed on Pluto to create ices of even greater complexity, Will Grundy, an investigator at the lab, astronomer at the Lowell Observatory and co-investigator on the New Horizons mission, told Space.com.

Any new ice observations from Pluto's surface that can't be found in the database that Grundy and his colleagues have created will mean another trip to the lab to try and match those measurements.

"We're going to be getting observations from Pluto with New Horizons that are going to light a fire under our butts," Grundy said.

"Our role here in the ice lab has been sort of a support role to try and understand how ice spectra behave under different circumstances," Stephen Tegler, the chair of Northern Arizona University's physics and astronomy department and researcher in the ice lab, explained to Space.com. "Then, armed with that broad view, you can take all that information, knowledge and experience, and say, 'OK, we have this particular fingerprint pattern. How does it relate to what we see in the ice lab?'"

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To measure the "fingerprinting" of a given ice sample, the researchers fire infrared light through the ices they create as they cool down. They track how the changes in temperature and phase of the ice affect which wavelengths of light are absorbed. Many people think "phase" refers to solid, liquid or gas — but it's much more complicated where these nonwater ices are concerned. They go through several different solid transitions: At certain temperatures, the already-solid ices will suddenly rearrange into a new crystalline setup. (Nitrogen, for instance, suddenly changes from a hexagonal to cubic crystal as it cools past 35.6 degrees Kelvin.)

Add combinations of different elements into the mix, which change at different temperatures, and it gets complicated fast. "Every combination, it's almost like we've got to come up with a new recipe to grow that very clear ice," Tegler said. Adding carbon monoxide, another gas present on Pluto, makes the recipes even more devilishly difficult — but also more useful to pinpointing the conditions on different parts of Pluto's surface, which might have the molecules in different proportions and temperatures.

"From the point of view of doing remote sensing, anything that changes is something that you could hope to detect from a telescope or from a spacecraft, so that's a valuable thing to know about," Grundy said.

Any unexpected, strange or inexplicable measurements will require new ices and new analysis to interpret. The lab has only scratched the surface on the gases the probe might encounter, say the team members.

"There are some things I haven't worked up the courage to try," Grundy said. "Another species that's on Pluto is hydrogen cyanide, which is even more toxic [than carbon monoxide] — and worse, it can be explosive as well," Grundy said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.