New Photos of Pluto Show a World More Complex and Beautiful Than Ever

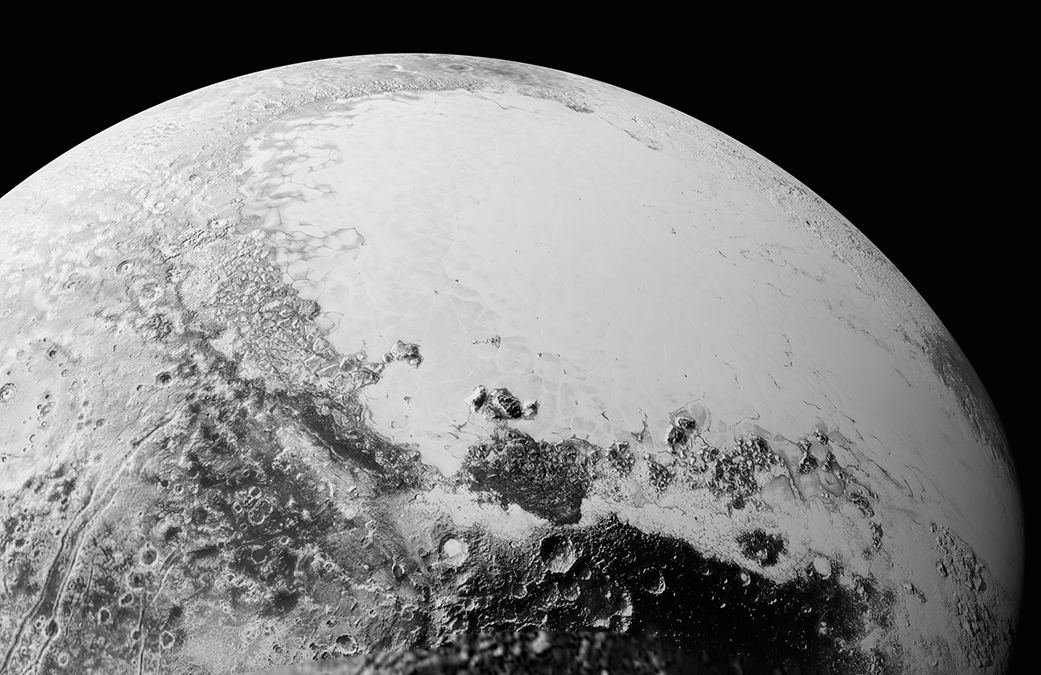

An "over-the-top" complex mix of craters, ice flows, mountains, valleys and apparent dunes coexist on Pluto in the latest amazing images from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft.

"Pluto is showing us a diversity of landforms and complexity of process that rival anything we've seen in the solar system," New Horizons' principal investigator Alan Stern, from the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, said in a statement. "If an artist had painted this Pluto before our flyby, I probably would have called it over the top — but that's what is actually there." At Space.com, we combined the new Pluto images into an awesome video.

After a break to send particle, solar-wind and space-dust data back to Earth, the New Horizons spacecraft has resumed sending images snapped during its July 14 flyby of Pluto. The new images released today (Sept. 10) have resolutions of up to 440 yards (400 meters) per pixel, and they show a chaotic hodgepodge of features offering many scientific puzzles. [See more of the new Pluto photos by New Horizons]

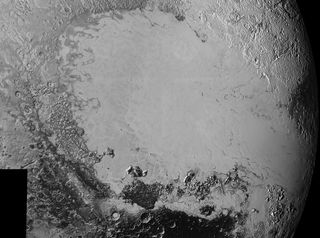

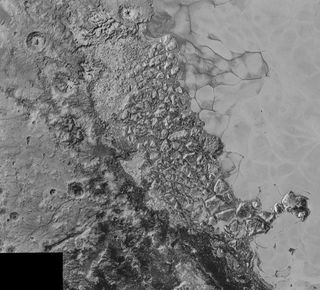

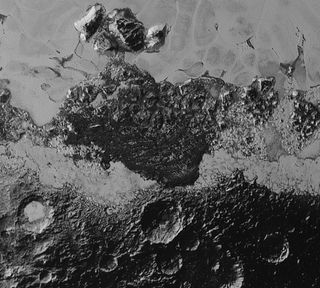

There may be dunes, officials said in the statement, adding that nitrogen ice flows travel from mountains down to plains, and a network of valleys seems to be carved by flowing material. Old, cratered terrain and "chaotically" jumbled mountains border new flat, icy planes in the segments scientists have seen.

"The surface of Pluto is every bit as complex as that of Mars," Jeff Moore, leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging (GGI) team at NASA's Ames Research Center in California, said in the statement. "The randomly jumbled mountains might be huge blocks of hard water-ice floating within a vast, denser, softer deposit of frozen nitrogen within the region informally named Sputnik Planum."

The flat plains of Sputnik Planum fall within the left side of Tombaugh Regio, the heart-shaped region first seen in July as New Horizons approached the dwarf planet from afar. It was one of the earliest features spotted on Pluto, and is only now revealed in full detail from 50,000 miles (80,000 kilometers) away.

Along the border of Sputnik Planum are what look like dark, windswept dunes, an unexpected surprise on a world that has too thin an atmosphere for wind, officials said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Seeing dunes on Pluto — if that is what they are — would be completely wild, because Pluto's atmosphere today is so thin," William B. McKinnon, a GGI deputy lead from Washington University, St. Louis, said in the statement. "Either Pluto had a thicker atmosphere in the past, or some process we haven't figured out is at work. It's a head-scratcher."

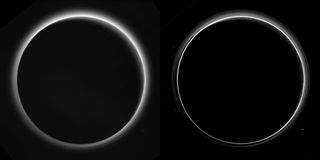

Researchers also received more data about Pluto's atmospheric haze. Imaged as Pluto blocked out the sun, this haze formed a glowing halo from the probe's perspective. There are more layers than the data initially suggested, and a soft atmospheric glow illuminates the planet's night side just before sunrise and after sunset.

"This bonus, twilight view is a wonderful gift that Pluto has handed to us," John Spencer, a GGI deputy lead also from the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado, said in the statement. "Now we can study geology in terrain that we never expected to see."

New Horizons continues to send back new images and data from the flyby while pressing onward, now over 43 million miles (63 million km) from Pluto and 3 billion miles (5 billion km) from the Earth.

Friday (Sept. 11), officials will release detailed images of Pluto's moons, taken during the flyby, that hint at a "tortured" geological past for Charon, officials say. Charon, like Pluto, is proving far more complicated than previously suspected.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.