Salty Water Flows on Mars Today, Boosting Odds for Life

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Liquid water flows on Mars today, boosting the odds that life could exist on the Red Planet, a new study suggests.

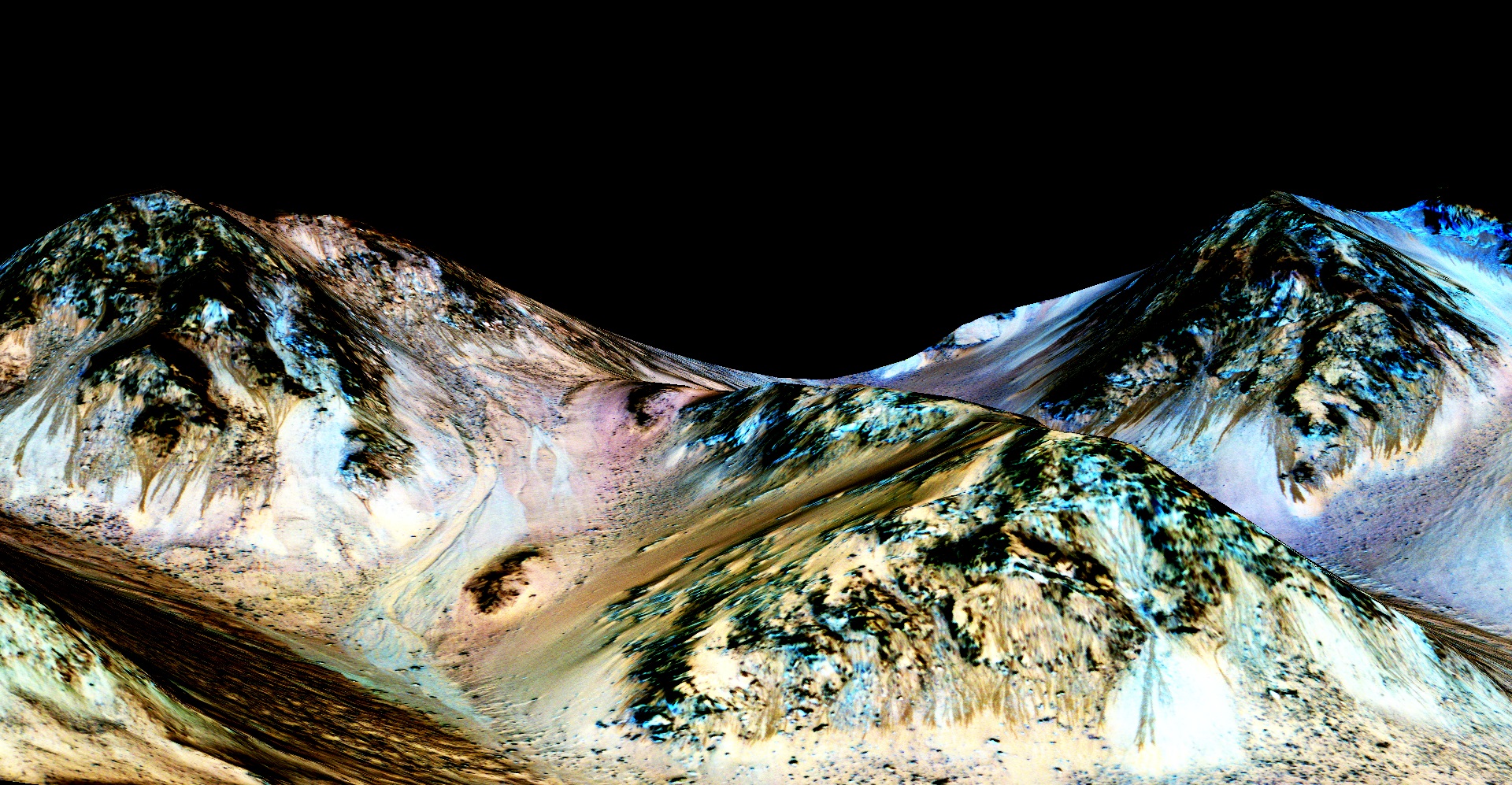

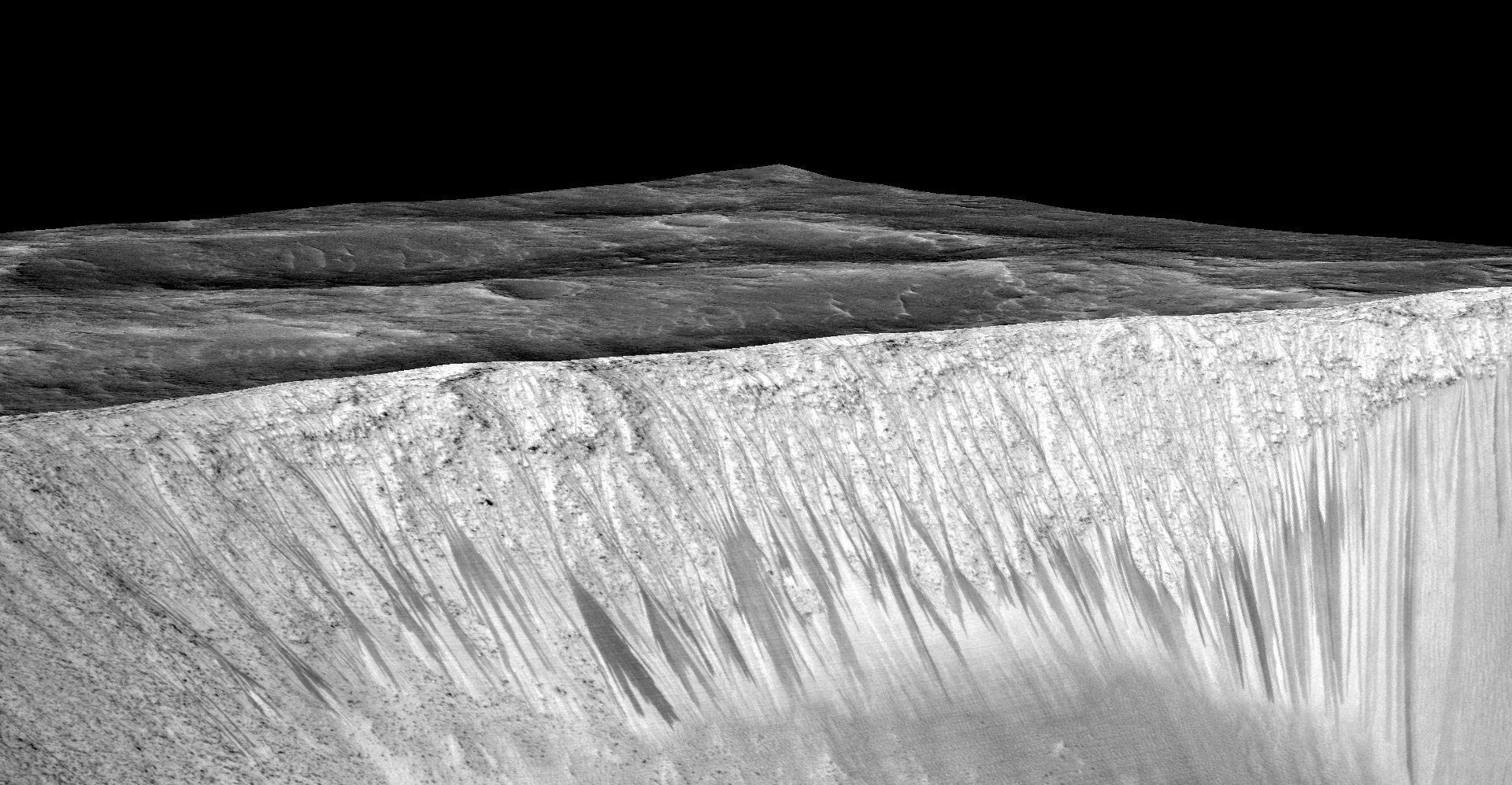

The enigmatic dark streaks on Mars — called recurring slope lineae (RSL) — that appear seasonally on steep, relatively warm Martian slopes are caused by salty liquid water, researchers said.

"Liquid water is a key requirement for life on Earth," study lead author Lujendra Ojha, of the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, told Space.com via email. "The presence of liquid water on Mars' present-day surface therefore points to environment[s] that are more habitable than previously thought." [Flowing Water on Mars: The Discovery in Pictures ]

Article continues belowOjha was part of the team that first discovered RSL in 2011, by studying images captured by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

RSL occur in many different locations on Mars, from equatorial regions up to the planet's middle latitudes. These streaks are just 1.6 feet to 16 feet (0.5 to 5 meters) wide, but they can extend for hundreds of meters downslope.

RSL appear during warm weather but fade away when temperatures drop, leading many researchers to speculate that liquid water is involved in their formation. The new study, which was published online today (Sept. 28) in the journal Nature Geoscience, strongly supports that hypothesis, team members said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ojha and his colleagues scrutinized data gathered about four different RSL locations by another MRO instrument, the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM).

"Using this instrument, we can deduce the mineralogical makeup of surface materials on Mars," Ojha said. "What we found was that at times and places when we see biggest RSL on the surface of Mars, we also found spectral evidence for hydrated salts on the slopes where RSL form."

Hydrated salts precipitate from liquid water, so detecting them is a big deal — especially since circumstances make it unlikely that CRISM could spot RSL water directly. (CRISM observes the Red Planet at the driest time of the Martian day, about 3 p.m., when any liquid surface water would likely have evaporated, Ojha said.)

"Due to that, I do not think we will ever find the RSL still in their liquid form at 3:00 p.m., so I think this hydrated signature of the salts is definitely a 'smoking gun,'" he said.

A previous study of RSL in Mars' huge Valles Marineris canyon system suggests that the features aren't exactly burbling streams, said study co-author Alfred McEwen of the University of Arizona.

"What we're dealing with is wet soil, thin layers of wet soil, not standing water," McEwen said today during a NASA press conference about the new discovery.

The RSL-associated salts appear to be perchlorates, a class of chlorine-containing substances that are widespread on Mars. These salts lower the freezing point of water from 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius) to minus 94 F (minus 70 C), Ojha said.

"This property vastly increases the stability of brine [salty water] on Mars," he said.

Perchlorates can absorb atmospheric water, Ojha said. But it's unclear if Mars' air is the source of the water in the brine flows. Other possibilities include melting of surface or near-surface ice or discharges of local aquifers.

"It is conceivable that RSL are forming in different parts of Mars through different formation mechanisms," the study team writes in the new paper.

Observations by NASA's Curiosity rover and other spacecraft have shown that, billions of years ago, the Red Planet was a relatively warm and wet world that could have supported microbial life, at least in some regions.

Mars is extremely cold and dry today, which is why the discovery of RSL sites has generated so much excitement over the past four years: The features point to the possibility that simple life-forms could exist on the planet's surface now.

But the new results don't imply that life thrives on Mars today, or even that this is a likely proposition, Ojha stressed. Perchlorate brines have a very low "water activity," he said, meaning that the water within them is not easily available for potential use by organisms.

"If RSL are perchlorate-saturated brines, then life as we know [it] on Earth could not survive in such low water activity," Ojha said.

The RSL discovery also has implications for the future human exploration of Mars, researchers said. NASA plans to put boots on the Red Planet by the end of the 2030s, and the presence of liquid water — even very salty water — on the surface could aid that ambitious effort.

Indigenous water "may decrease the cost and increase the resilience of human activity on the Red Planet," study co-author Mary Beth Wilhelm, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said during today's press conference. "Looking forward, it is imperative for us to further understand the source of the water for these features, as well as the amount."

This story was updated at 1 p.m. EDT.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.