Many of Earth's mass extinctions over the eons have been caused by comet strikes, a new study suggests.

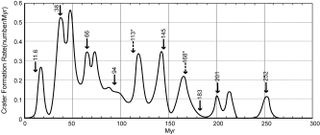

Over the past 260 million years, cratering rates on Earth have peaked every 26 million years or so, in tune with a previously noted cycle of mass-extinction events, researchers found. Furthermore, five of the six largest impact craters known from the last quarter-billion years — including the 112-mile-wide (180 kilometers) crater associated with the demise of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago — were gouged out at roughly the same time that a mass extinction occurred.

"The correlation between the formation of these impacts and extinction events over the past 260 million years is striking and suggests a cause-and-effect relationship," study lead author Michael Rampino, a geologist at New York University, said in a statement. "This cosmic cycle of death and destruction has without a doubt affected the history of life on our planet." [Wipeout: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

Rampino and co-author Ken Caldeira, of the Carnegie Institution for Science's Department of Global Ecology, discovered the pattern after analyzing a data set that featured newly revised, more accurate estimates of crater ages.

The finding, which was published online last month in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, lends support to the venerable but much-debated "death from above" hypothesis set forth to explain the periodicity observed in Earth's mass extinctions.

Every 26 million years or so, the idea goes, our solar system travels through the Milky Way galaxy's dense midplane, and the resulting gravitational jostles send comets that normally reside in the distant Oort Cloud barreling toward Earth and other planets close to the sun.

Much of the gravitational perturbation, according to this hypothesis, is caused by mysterious dark matter, which far outweighs "normal" matter but neither emits nor absorbs light and is therefore difficult to study. And dark matter may further contribute to mass extinctions, Rampino suggested in a controversial study published earlier this year, by heating up Earth from the inside, leading to huge, climate-altering volcanic eruptions.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While Rampino and Caldeira identified 10 mass extinctions in the last 260 million years, some other metrics recognize just five such events in the past 450 million years or so. (It depends on how high above background rates an extinction event must be to qualify as "mass.")

The worst of these "Big Five" events occurred about 250 million years ago, at the end of the Permian geologic period. During this event, known as "The Great Dying," about 90 percent of Earth's species was lost. For comparison, scientists estimate that the dino-killing event 65 million years ago took out 50 to 75 percent of all species.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.