Giant Comets Periodically Smash Earth, Scientists Say

Giant comets that originate in the planetary fringes of the solar system pose a greater threat of colliding with Earth than do asteroids, which originate closer to the sun, a new review paper argues.

In the last two decades, scientists have discovered hundreds of giant comets (known as centaurs) in the region near Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, according to a statement from the Royal Astronomical Society.

No centaur poses a known immediate threat to Earth, but the discovery of this massive population has led a group of astronomers to re-assess the threat of these seemingly distant bodies to this planet. [Pictures of Potentially Dangerous Asteroid]

Estimates currently suggest that one of these giant comets crosses Earth's orbit on average only once every 40,000 to 100,000 years, at which time the comet is believed to break up into dust and debris that can collide with the planet. These collisions may be responsible for environmental upheavals in Earth's past; they may even be associated with the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, the statement said.

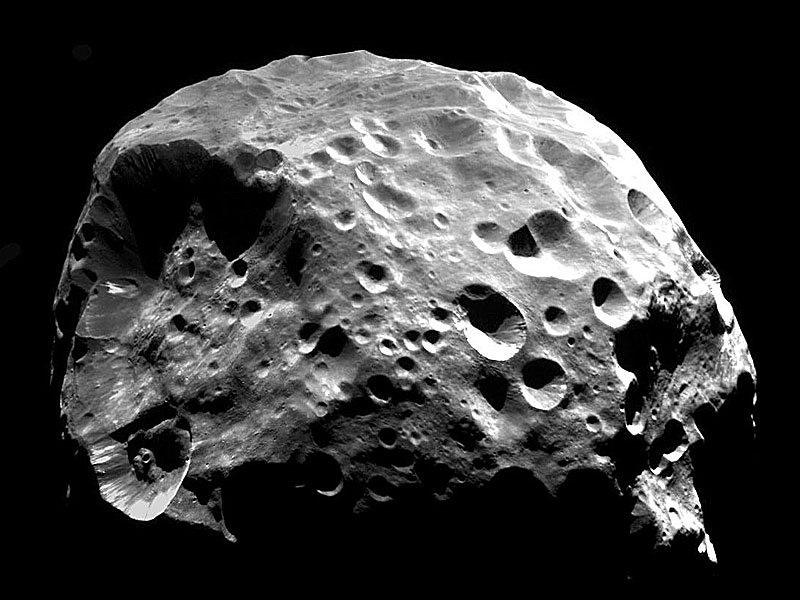

Centaurs are between 31 and 62 miles (50 and 100 kilometers) across and move in unstable orbits near the giant planets. Occasionally, the gravitational influence from one of these planets can send the centaur careening toward Earth.

"In the last three decades, we have invested a lot of effort in tracking and analyzing the risk of a collision between the Earth and an asteroid," said Bill Napier, an honorary professor in the Centre for Astrobiology at the University of Buckingham in the United Kingdom, in the statement. Napier is first author on a review paper that aims to re-assess the threat of centaurs to the Earth.

"Our work suggests we need to look beyond our immediate neighborhood, too, and look out beyond the orbit of Jupiter, to find centaurs," Napier said. "If we are right, then these distant comets could be a serious hazard, and it's time to understand them better."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The statement said that "known severe upsets" of Earth's environment, accompanied by a disruption in how ancient civilizations evolved, mean that a centaur must have been in Earth's neighborhood roughly 30,000 years ago. This centaur would have shed clumps of debris ranging from fine dust to pieces several miles in diameter, some of which hit Earth. The researchers point to the existence of many submillimeter craters in rocks brought back from the moon by Apollo astronauts. (Because the moon has no geologic activity or atmosphere, craters are better preserved on its surface). Since the craters were mostly 30,000 years old or younger, it suggests an influx of dust in the solar system after that time period.

Other environmental disruptions, in 10,000 B.C. and 2,300 B.C., suggest centaurs could have been responsible for changes in the Earth at those times, the statement said.

The review paper was published in the Astronomy & Geophysics journal of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.