Some hardy Earth organisms may be able to survive on Mars, a new study suggests.

Two species of tiny fungi from Antarctica survived an 18-month exposure to Mars-like conditions aboard the International Space Station, according to the study, which was published last month in the journal Astrobiology.

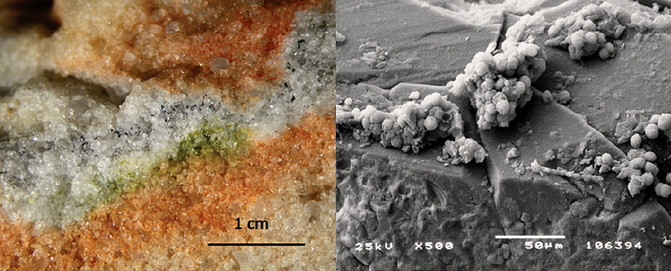

The researchers studied two species of microscopic fungus, Cryomyces antarcticus and C. minteri, that were collected from Antarctica's McMurdo Dry Valleys — one of the most Mars-like environments on Earth. These fungi are "cryptoendolithic," meaning that they live within rock cracks. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)]

The fungi were placed within an experiment platform developed by the European Space Agency called EXPOSE-E. Spacewalking astronauts affixed EXPOSE-E to the orbiting lab's exterior.

For 18 months, half of the Antarctic fungi were exposed to simulated Mars conditions — specifically, an atmosphere consisting of 95 percent carbon dioxide, with a pressure of 1,000 pascals (about 1 percent that of Earth at sea level); and high levels of ultraviolet radiation. The other half of the fungi served as a control population.

"The most relevant outcome was that more than 60 percent of the cells of the endolithic communities studied remained intact after 'exposure to Mars,' or rather, the stability of their cellular DNA was still high," study co-author Rosa de la Torre, of the National Institute of Aerospace Technology in Spain, said in a statement.

However, less than 10 percent of the fungi were able to proliferate and form colonies after experiencing the Mars-like conditions, the researchers found.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This work is part of a larger suite of studies aboard the space station called the Lichens and Fungi Experiment (LIFE), "with which we have studied the fate or destiny of various communities of lithic organisms during a long-term voyage into space on the EXPOSE-E platform," de la Torre said in the same statement.

"The results help to assess the survival ability and long-term stability of microorganisms and bioindicators on the surface of Mars — information which becomes fundamental and relevant for future experiments centered around the search for life on the Red Planet," she added.

Searching for signs of life on Mars is a high priority for both the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA. Both agencies plan to launch life-hunting rovers toward the Red Planet in the coming years; ESA's ExoMars rover is scheduled to blast off in 2018, and NASA's 2020 Mars rover will launch two years later, if current schedules hold.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.