Mercury's Carbon-Rich Crust is Surprisingly Ancient

Before its planned crash into Mercury last year, NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft gave scientists a parting gift.

In its final orbits, MESSENGER not only confirmed that Mercury's dark hue is due to carbon, but also revealed that the carbon wasn't deposited by impacting comets, as some researchers suspected.

Fuzzy to Clear: Space Robots Snap Solar System Into Focus

Instead, scientists now believe they are seeing remnants of the planet's primordial crust, which likely formed when a global ocean of super-heated magma cooled, allowing minerals to solidify.

Computer simulations and experiments show that most of these crystallized minerals would sink — with one key exception. Graphite, the studies show, would float.

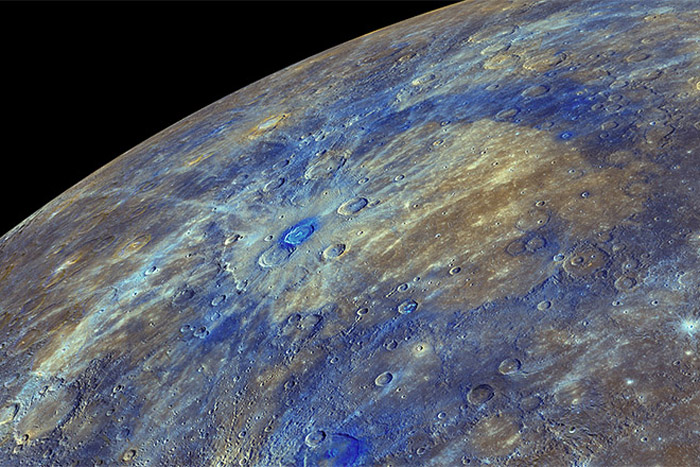

Scientists used an instrument on MESSENGER called a neutron spectrometer to make low-altitude measurements of the darkest regions on the planet's surface, which were suspected of having the most low-reflectance material (LRM.)

"The measurements showed enhanced fluxes of thermal neutrons over three areas of LRM, so only graphite as the darkening agent fits both the spectral reflectance observations and the neutron measurements," MESSENGER's lead scientist Sean Solomon, with Columbia University, wrote in an email to Discovery News.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NEWS: Mercury's Speedy Spin Hints at Planet's Insides

Scientists also were able to match the carbon-rich material with large impact craters, evidence that the material stemmed from deep within Mercury's crust and was exposed after an impacting body gouged out a crater.

"Because LRM deposits on Mercury are all associated with material excavated from depth by large impact craters, they must come from the mid to lower crust," Solomon said.

Scientists estimate the ancient crust was about .62 mile, or 1 kilometer, thick.

The crust of present-day Mercury has been bashed by impacts, covered with lava, melted and otherwise disturbed.

"The processes … would dilute any primordial crust," physicist Patrick Peplowski, with Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab, and colleagues write in a paper published this week in Nature Geoscience.

NEWS: Strange 'Hollows' on Mercury Revealed by NASA Probe

"This inference adds to our deepening appreciation that Mercury formed from a portion of the early solar nebula that was chemically much more reduced and was rich in other volatiles (such as sulfur, sodium, potassium and chlorine) compared with the portions of the nebula well sampled by Venus, Earth and Mars," Solomon said.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Irene Klotz is a founding member and long-time contributor to Space.com. She concurrently spent 25 years as a wire service reporter and freelance writer, specializing in space exploration, planetary science, astronomy and the search for life beyond Earth. A graduate of Northwestern University, Irene currently serves as Space Editor for Aviation Week & Space Technology.