Ceres' Puzzling Bright Spots, Giant Mountain Feature in New Close-Up Photos

THE WOODLANDS, Texas — Ceres is coming into focus, but many mysteries about the dwarf planet remain.

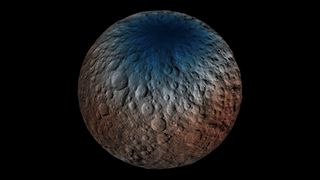

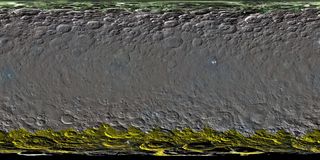

Newly released images captured by NASA's Dawn spacecraft reveal a close-up look at Ceres' odd bright spots and giant mountain, and hint at the existence of ice sheets at the dwarf planet's poles.

"Clearly, we have a lot of work to do to put together a self-consistent story [about Ceres]," Dawn's deputy principal investigator Carol Raymond, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said here at a press conference yesterday (March 22). [See More Pictures of Ceres' Weird, Changing Spots]

Still, Raymond said it's fairly clear that "Ceres is a former ocean world where the ocean froze."

Dawn has been orbiting Ceres — the largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter — since March 2015. But the probe only recently moved to its closest, final science orbit, which lies at an altitude of 240 miles (385 kilometers) above Ceres' surface.

Bright spots and a unique mountain

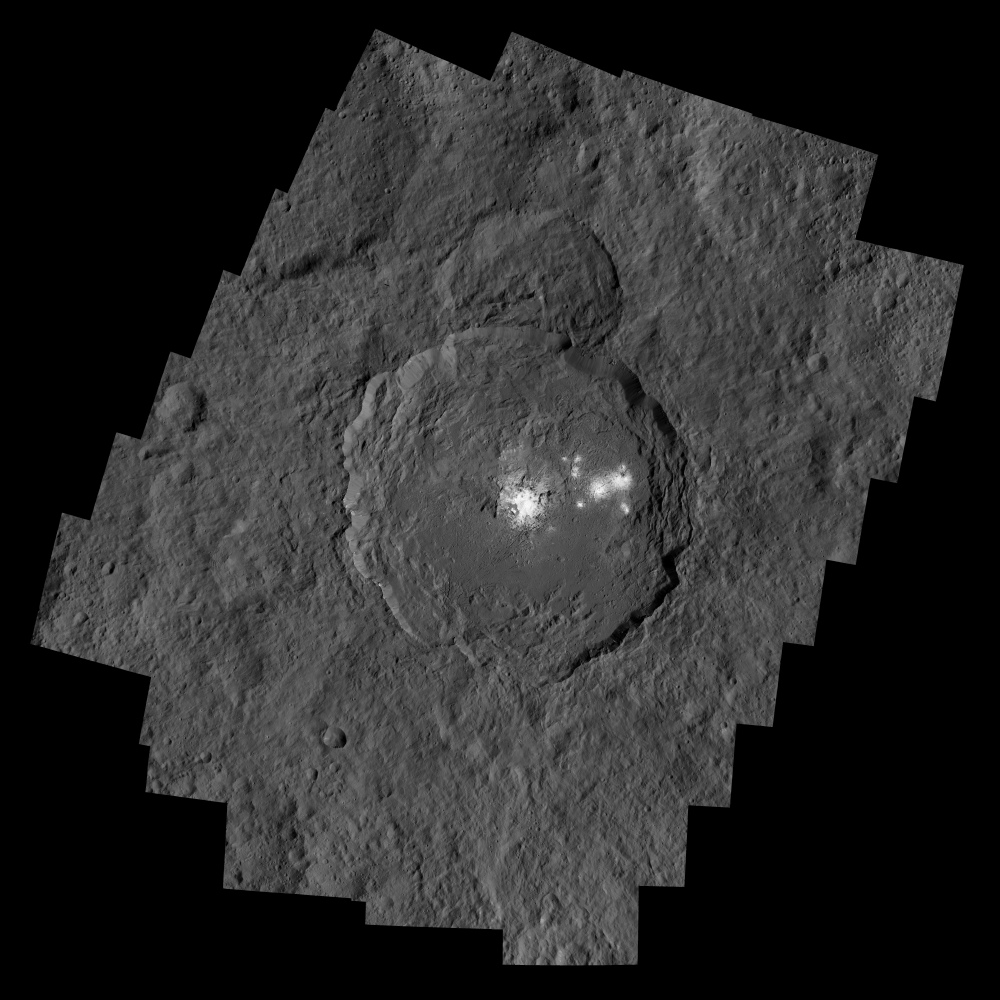

As Dawn closed in on Ceres last year, the spacecraft snapped tantalizing images of bright spots on the dwarf planet's surface. Dawn eventually resolved a single bright blob inside the 57-mile-wide (92 km) Occator Crater into multiple spots.

According to Dawn co-investigator Ralf Jaumann, a planetary scientist at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Berlin, as the spacecraft drew closer to the dwarf planet, "we had no geologic evidence" about what the bright spots could be.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Dawn eyed the bright spots, and the rest of Ceres' surface, from a series of three successively closer-in orbits over much of last year. Then, in October, the probe began to spiral in toward its fourth and closest orbit around the 590-mile-wide (950 km) dwarf planet, finally reaching the mission's destination in mid-December.

The sharp views from just 240 miles (385 km) overhead are shedding new light on the bright spots, he said.

"Now that the resolution is 30 meters [100 feet] [per pixel], we can really see geological features," Jaumann said.

The center of Occator Crater, where the most famous and dramatic of the bright spots reside, contains a dome rising from its heart. Jaumann expressed confidence that Dawn data from the close-in orbit will help scientists understand more about the spots and Ceres in general.

A full understanding may take some time, however. Raymond said it can be difficult to predict where Dawn will pass over the surface, making it a challenge to understand some features. [Bright Spots on Ceres Change Every Day (Video)]

"We still haven't built up the data sets that we would like in Occator," she said.

One of the biggest issues that Dawn is revealing involves an age paradox. One explanation for the bright spots is that they were uncovered when a large object crashed into Ceres. As heat from the impact penetrated the surface, salts and volatile elements such as water would have been heated and mixed. As the liquid material evaporated, it could have left salts behind to twinkle at the surface. But Occator is about 80 million years old, and bright material should not have lasted nearly that long on the surface, researchers said.

"It's hard to keep things bright on a planetary surface over time," Raymond said.

Another puzzling feature on Ceres is the towering mountain known as Ahuna Mons. The new Dawn images reveal that the top of the 3-mile-high (5 km) mountain is made up of material similar to the surface around it, while the sides are composed of completely different material altogether. Jaumann said this suggests Ahuna Mons has pushed its way up from the subsurface.

"Something [has come] up from the subsurface and pushed the older surface up," he explained.

Material welling up through a small crack in the ground could have formed the mountain through volcanic processes, Jaumann said. Alternatively, if the material beneath the ground is less dense than the surface, that material could rise to the top, pushing up a mountain. While both processes have been observed in magma and lava regions in the solar system, neither has been observed in icy environments.

"It really makes the mountain a little bit unique in the solar system," Jaumann said.

Ice sheets and odd craters

In December, Dawn's Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector (GRaND) instrument began observations. As fast-moving cosmic rays interact with planetary surfaces, they excite particles and reveal insights about the elements just beneath the ground. GRaND will reveal information about a wealth of these elements, but the first results are focused on hydrogen due to its relation to water-ice.

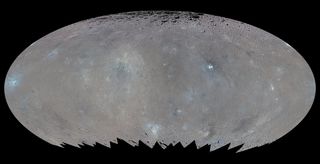

These GRaND results reveal that Ceres' hydrogen is preferentially concentrated at the poles, allowing scientists to test the long-standing hypothesis that ice sheets lie below the surface farther from the equator.

Dawn's visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIR) has also been hard at work. By examining how the surface reflects sunlight at various wavelengths, VIR helps to identify minerals across the dwarf planet.

One puzzling region surrounds Haulani Crater. According to VIR instrument lead scientist Maria Cristina de Sanctis, of the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome, Haulani stands out as an anomaly because the material scooped out by the impact is different from the stuff at the center of the crater. VIR is helping to solve some of the mysteries surrounding the crash site.

"Thanks to new data we will be acquiring soon in lower orbits, I think we [will be able to] disclose a little more about its orbit," de Sanctis said.

The $466 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007. Dawn made history in March 2015 when it arrived at Ceres after a 14-month visit to the protoplanet Vesta (the second-largest denizen in the asteroid belt), becoming the first satellite to orbit two solar system objects beyond the Earth-moon system.

Dawn also became the first mission to visit a dwarf planet, arriving only a few months before NASA's New Horizons mission flew by Pluto.

Dawn is now showing some signs of wear and tear. Before it left Vesta, the probe had lost two of its four reaction wheels, which help to point the spacecraft precisely. That hasn't kept Dawn down, however, nor should it in the future. The team can still complete its primary mission if it loses all four wheels, by using just the probe's thrusters to maintain orientation, Raymond said.

"If the wheels continue to operate, it allows us to have more lifetime," she said.

There is sufficient fuel on board that, without the wheels, the spacecraft could last until the beginning of August. With them, Dawn could last another year.

"What we are certain [of] is that we can finish our primary mission," Raymond said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookor Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd