'Laser Cloak' Could Hide Earth from Evil Aliens

A simple laser beam could disrupt aliens' observations of Earth, making it look like there's nobody home on the third rock from the sun, a new study suggests.

David Kipping, an astronomer at Columbia University in New York, said he first considered this idea when he heard about the strangely dimming star that was detected recently by NASA's Kepler space telescope. Researchers speculated the signal could have come from an "alien megastructure" orbiting the star.

That's a remote possibility, many scientists stressed; the star's strange signal likely has a natural cause. But the Kepler observations got Kipping thinking about ways humanity could alter the signals it sends into space — or hide them altogether from life-hunting aliens, who may have malicious intentions. [13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Aliens]

He and Columbia graduate student Alex Teachey concluded that it would be surprisingly easy to wipe out Earth's signal, distort it to look strange or even edit out the fingerprint of life — provided researchers knew the location of the snooping aliens.

"We essentially played the thought experiment that if we really had xenophobic tendencies and wanted to avoid the Earth being discovered (as Stephen Hawking and others have been warning about), could we hide the Earth from alien planet-hunters?" Kipping said in an email.

How to build a cloaking device

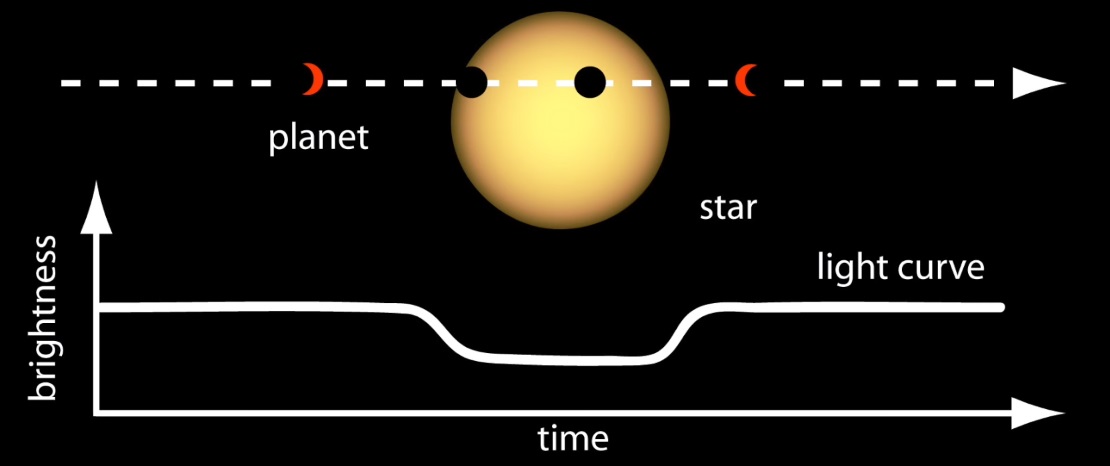

The key to Kipping and Teachey's thinking lies in the way humans have identified most planets around other stars, a process called the transit method. This strategy, which has most famously been employed by the Kepler spacecraft, detects tiny dips in the brightness of stars, which can indicate an orbiting planet.

The transit method could theoretically be used by alien civilizations to detect Earth, too. But there's a way to trip up such extraterrestrial searches, Kipping and Teachey said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"To make it look like the planet is not there at all, you've got to get rid of that dip. You've got to fill in the missing starlight," Teachey said in an explanatory video.

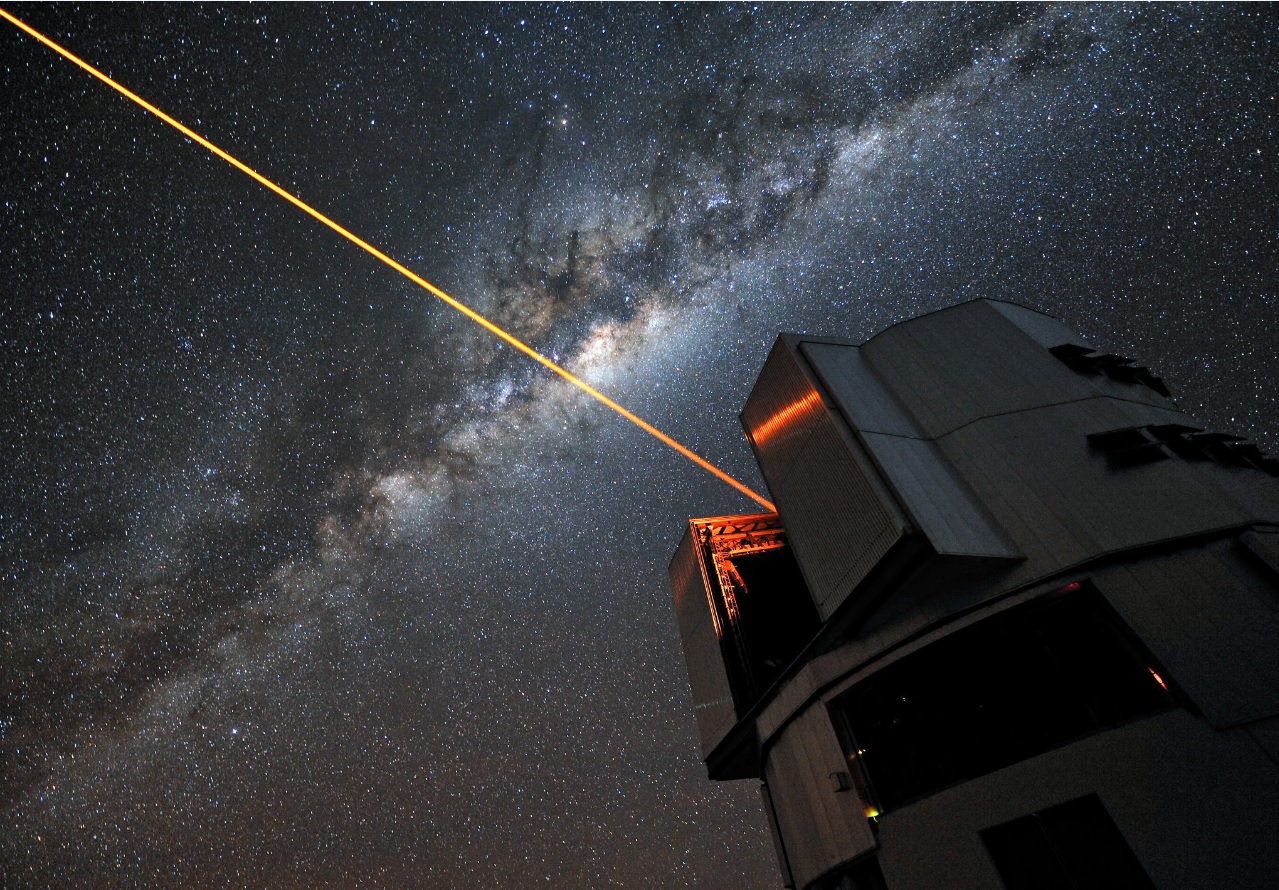

Engineers could shine a very bright laser or collection of lasers toward a star suspected of hosting intelligent aliens during the time Earth was passing in front of the sun from the other planet's perspective. Then, aliens making measurements wouldn't see any change in solar brightness.

"I started to think about lasers," Kipping told Space.com. "Most people might have stopped there, because the sun emits so much light — how could you possibly produce a laser beam which could ever compete with the sun? But it turns out, when you actually run through the equations, it's really not that bad." [How to Discover an Alien Planet (Video)]

"We could build this next week if we wanted to," Teachey added.

To alter Earth's signature as seen by an alien version of Kepler, a laser system would have to emit 30 megawatts of power for about 10 hours per year, coinciding with Earth's passing in front of the sun, the duo calculated.

That equates to significantly less than the energy the International Space Station gathers in a year with its solar panels, Kipping said, or the energy used by about 70 homes over the course of a year. Such a laser system, either on Earth or in orbit, could charge its solar-powered batteries for most of the year and then release the high-powered blasts at just the right time, brightening when the sun's light would normally dim.

While a laser of that intensity hasn't been built before, the researchers said, such a cloaking system could also use multiple smaller lasers, all shining in the same direction. The alien star would be so distant that such a difference would be indistinguishable. Laser beams are tightly focused, but at greater distances, the beams will have grown large enough to require less precise aim.

By varying the wavelength and strength of the beams, humans could conceal Earth from more complicated detectors. Such a "cloak" that concealed all wavelengths would take about 250 megawatts of power, with lasers blasting at different wavelengths, the researchers said. The laser strategy could also alter Earth's signature to look like almost anything, even something that appears distinctive and artificial, the scientists said, like the New York skyline or a featureless box.

But perhaps the most interesting use, the researchers said, would be as a "bio-cloak," which would actually use less power than would be required to totally conceal the planet. When a planet crosses its star's face, a little bit of light passes through the planet's atmosphere, and researchers can determine the atmosphere's makeup based on the wavelengths of that light. By sending laser beams that are the inverse of certain wavelengths, humanity could conceivably edit out the life-generated "biosignatures" in Earth's atmosphere, Kipping said.

"We can actually cancel those features out, such as oxygen," he said. "The alien civilization is going to detect your planetary transit. They're going to detect your planetary radial velocity, but then when they 'smell' the atmosphere, it would not look like a tasty planet. It would just look like a dead world."

While a planet that was fully cloaked could still be detected by other means, such as by the gravitational pull it exerts on its star, this kind of cloak would arouse less suspicion, because the planet would be there as expected, just without signs of life.

"We feel like this is the most deceptive cybercloaking you could possibly do, because then everything adds up — there's no missing piece to the puzzle," Kipping said. "And that would be a very difficult cloak to see." [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

Kipping and Teachey laid out their thinking in a study published Thursday (March 31) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Many possibilities

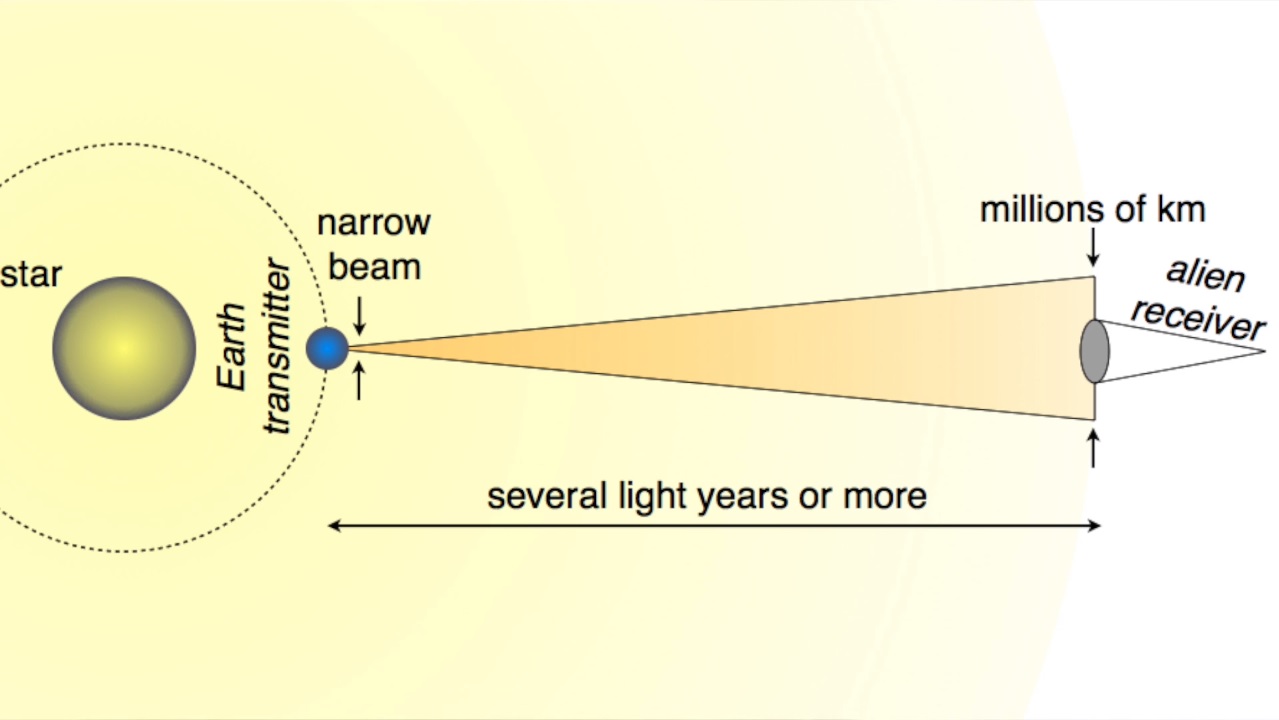

Concealing Earth's existence from extraterrestrials, or announcing its presence with an artificial light curve, would work only if humanity knew or suspected where those aliens were living. But the concept is still intriguing as scientists look out to read other stars' light signatures and speculate about alien astronomers reading signals from Earth.

Kipping and Teachey suggested that alien civilizations could communicate with each other during transits by varying their light signatures, because individuals investigating a planet are likely to watch it as it passes in front of its star. Alien lasers could even encode information to transmit, the researchers said.

One possible next step, they added, would be to look more carefully through archival Kepler data to search for artificial signatures.

Jason Wright, an astronomer from Pennsylvania State University, recently published a paper about how scientists could identify advanced civilizations around other stars. "Alien megastructures" would dim stars more than expected, whereas lasers would tend to brighten them, but "we should look for both," Wright told Space.com.

"The fact that Kepler looked at 100,000 stars and didn't see much of anything along those lines suggests that that is pretty rare in the galaxy," Wright added. "And we should look more closely to see if there are things that aren't totally obvious."

In terms of this particular technology on Earth, "The only time it'd be useful for us is if we had some knowledge of alien civilizations along the thin strip of the sky that would see Earth transit the sun," he said.

Avi Loeb, who chairs the astronomy department at Harvard University in Massachusetts, told Space.com that the laser-cloaking method assumes researchers know where to look, that aliens aren't observing from moving spaceships and that putative extraterrestrial observers are mainly investigating planets by looking for transits across stars.

Energy demands would quickly grow as a civilization tried to hide from, or signal to, an increasing number of star systems, Loeb added. But the laser cloak is still an interesting new idea to add to the arsenal in the search for extraterrestrial life, he said.

"If there is a literature of ideas like this one, ideas that people proposed for potential signals that are artificial — the richer the literature is, the better it is," Loeb said. "The moment we find something artificial, it will change everything. It's good to have the imagination at work prior to seeing something unusual, so we are aware that there are possibilities beyond what we expect."

"I don't think anyone's thought of this particular application before," Wright said. "I think it just emphasizes how little energy is actually required to get someone's attention across the galaxy."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.