BEAM Me Up! Prototype Space Room Could Lead to Inflatable Moon Bases

This Friday (April 8), SpaceX is scheduled to launch a Dragon cargo spacecraft toward the International Space Station, carrying the first expandable habitat that will be occupied by humans in orbit.

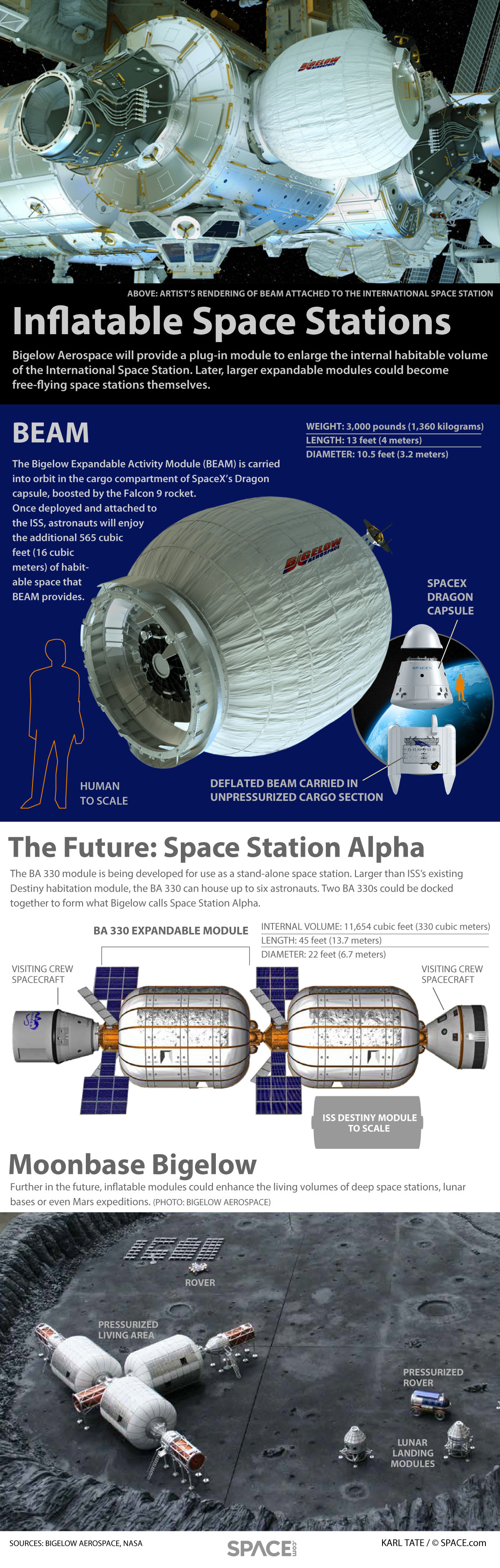

The Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) will be folded up into the trunk of the Dragon spacecraft like a parachute that is ready to be unfurled. The station's robotic arm will remove BEAM from the trunk, attach it to the Tranquility Node, and it will expand to more than five times its total compressed size in about 45 minutes.

It doesn't take a spaceflight industry expert to start dreaming about what expandable habitats could mean for future space exploration. Why not put up a dozen space stations orbiting the Earth? Humans could use them to set up colonies on the moon or Mars. What's to stop an eccentric billionaire from starting a space hotel? Robert Bigelow, founder and head of the company that made BEAM, talked to Space.com about the company's goals for the next 20 years, and the issues that stand in the way of the company's efforts to achieve them. [Bigelow's Inflatable Space Station Idea in Photos]

Expandable is better

A central limiting factor to the possible size of space-based habitats or structures is the size of the payload bay on the spacecraft that carries it up to space. Many of the American pieces of the space station were sent up in the space shuttle's bay, which was roughly large enough to fit a school bus. (Russia also took the approach of building a new spacecraft that could withstand the trip to space, and then used the spacecraft itself as a module for the station).

"Bigelow habitats are lighter and take up substantially less rocket fairing space, and are far more affordable than traditional, rigid modules," according to Bigelow press release. And for anyone worried about the safety of something that expands like a balloon in an environment that is fairly hostile to life, the company says its habitats provide "enhanced protection against radiation and physical debris" compared to metallic structures.

BEAM is built out of a proprietary "soft-goods, expandable material." The load-bearing structure is made from something similar to Vectran, a manufactured fiber made from a liquid-crystal polymer that is used in some space suits, company representatives said in last week's telecom. BEAM is covered by a Micrometeoroid and Orbital Debris protection layer, which is also proprietary to Bigelow Aerospace. Company representatives speaking during a NASA teleconference in April said their structures are up to the standards set for all ISS structures.

BEAM will only have one-fifth the livable space of the station's Harmony Module — but it also only has one-tenth of Harmony's mass. When packed, BEAM can be reduced to about half of its normal width and about three-quarters of its normal length. Thus, an expandable habitat that, when compressed, was the size of the Harmony module, could expand to be even larger, thus making it possible to get bigger space habitats into orbit without having to build bigger cargo carriers.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That's what Bigelow Aerospace is currently driving at. In March 2015, NASA announced that as part of its Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) project, the agency has a contract with Bigelow to develop "ambitious human spaceflight missions that leverage its innovative B330 space habitat." The B330 is an expandable habitat with 330 cubic meters of livable space — 20 times more than BEAM and 4.5 times more than Harmony. Bigelow said that by 2021, the company will be prepared to launch up to two of the B330s. Whether or not they launch will depend on whether or not the company has a customer who wants to use the habitat, and whether or not there is an affordable way to send people there. [Inflatable Space Station by Bigelow Aerospace (Infographic)]

A ticket to space

If inflatable space habitats are such a good idea, then why is Bigelow Aerospace the only company or agency that has made any significant progress toward making them?

"[Why is Bigelow the only company] that's foolish enough to do it?" Bigelow asked, finishing my question for me. He laughed, but then said, "In all seriousness, it is a leap of faith in a sense, because we have been so far out in front of everything."

Bigelow owns the hotel chain Budget Suites of America, and it was from that enterprise that he made enough money to start a company that would build expandable habitats. It was an idea that NASA had started investigating in the 1950s, according to Bigelow Aerospace's website, and it was work on expandables that led to the invention of Mylar. Ultimately, a lack of sufficiently strong, yet flexible materials stopped that line of research within the agency. Work on expandable habitats was briefly revived in the 1980s and again in the 1990s, but NASA wasn't able to keep the project alive.

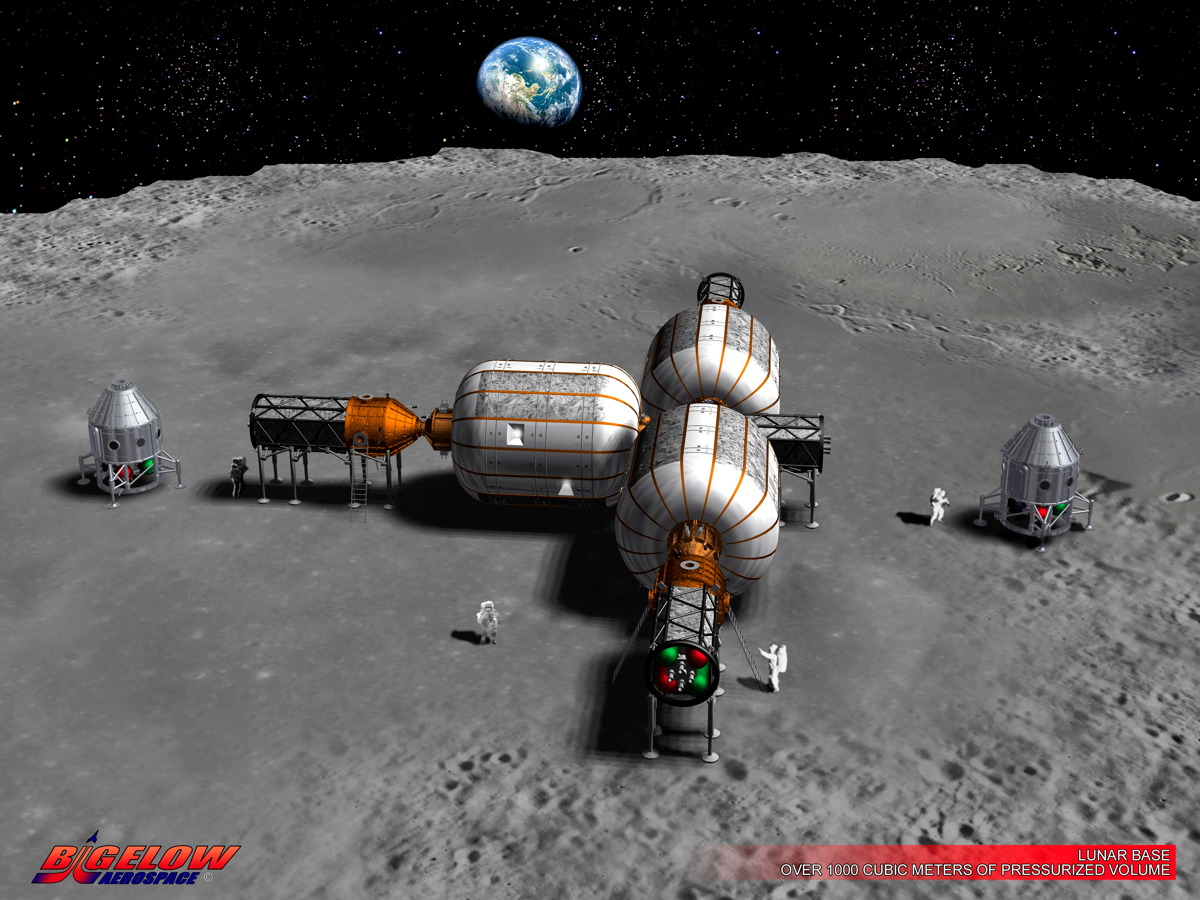

Expandable space habitats are being discussed by people in both the public and the private spaceflight industry sectors — animations and artists' renditions like this one show expandable habitats playing a role in future space exploration endeavors. But, perhaps the reason no one has invested as heavily in actually building them is because a space destination is no good without a way to get there.

"Transportation has been our Achilles' heel in terms of getting into a business mode, ever since we started the company," Bigelow said.

The company struggled for years without success to get its first two in-space test habitats, Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, into orbit using U.S.-based launch options, and then spent years working to get past regulations that made it difficult to launch them via a Russian-based space travel provider. There are an increasing number of U.S.-based companies that will fly cargo into space, but Bigelow said his major concern is how humans will reach these space habitats.

Right now, the only way for humans to get to orbital space is on a Russian Soyuz capsule. NASA currently pays nearly $82 million per astronaut for space on the Soyuz.

"We would never attempt a business case based on the kind of pricing per seat that NASA is willing to pay," Bigelow said. "It wouldn't work."

Hope is on the horizon, however. SpaceX and Boeing have signed contracts with NASA to launch humans into space as early as 2017. SpaceX is also aiming to drastically reduce the cost of each flight by engineering reusable rocket boosters.

"At this juncture, we are assuming that SpaceX is going to perfect its ability first, before other companies, to affordably move people to and from low-Earth orbit," Bigelow said. Affordability is "a key word," he said.

The commercial spaceflight industry is still at a tentative stage, said Jeff Greason, a co-founder of the spaceflight company XCOR, who spoke with Space.com at the SpaceCom Expo in Houston, in November 2015. He said the success and progress of transportation providers is moving forward, but "we have not yet reached the point where I think it's irreversible."

"The enterprise is much bigger than just the transportation segment. But it's all enabled by the transportation segment," Greason told Space.com. "So, if the transportation's not there, then all of the other great things we can do, which make up much more of the business, can't happen. So transportation is key."

For its habitats to succeed, Bigelow's company needs transportation, but that need is a two-way street: Transportation providers need a place to take people and cargo. The topic of space destinations was also a discussion point among experts at the 2015 SpaceCom Expo. The spaceflight community is understandably concerned about NASA's plans for supporting the International Space Station after 2024, when the agency's current commitment to maintain its side of the station ends. Having an operating laboratory in low Earth orbit provides commercial space companies with a regular customer for sending cargo and (soon) humans. It also provides a platform for space-based science, and will provide a place where explorers can prepare for more trips to other space destinations.

If Bigelow's plans stay on track, and it attracts the right customers, his company could relieve that threat by providing new laboratories in low Earth orbit. Countries without space programs or without a stake in the ISS could send astronauts to space without having to build the infrastructure that NASA and other space agencies currently have.

Bigelow said the company has "had discussions with foreign countries who have their own space agencies … for a number of years," as well as with countries who do not have their own space agencies. Already, he said, there are countries interested in using BEAM to pursue commercial activities.

Bigelow said he envisions that between 2021 and 2031, the Bigelow B330s would be added on and expanded, creating "a large conglomerate of habitats" that could be owned by different customers, or jointly owned by multiple partners. If money can be generated from those LEO destinations, Bigelow said he'd like to see that put toward lunar settlements.

"We would transition some of the client menu that we would have in LEO to folks who would want to be involved in some kind of business activity on the moon. And I think that by 2031, that's practical," Bigelow said. "We would also like to be part of a conglomerate of folks. … I see our role as perfecting our art and being able to provide habitats for deployment in different environments in conjunction with other space or nonspace folks putting companies together to promote these kinds of activities. So I don't look at it as [if] we intend to do this alone." [Inflatable Habitats: From the Space Station to the Moon and Mars?]

Working with NASA

Eric Stallmer is president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation (CSF), the "industry association of leading businesses and organizations working to make commercial human spaceflight a reality," according to the CSF website. Stallmer said he's an optimist about BEAM and Bigelow Aerospace's future plans for its expandable habitats. He's also a realist, and recognizes that there are still significant challenges facing the company.

"There's a lot of elements to this, and just because the BEAM is going up, doesn't mean, you know, we're going to have a lunar base next week," Stallmer said. "I think [Bigelow is] paving the way, I think they're pioneers. … They did something that traditionally only a government could do or only a sovereign nation could do. And they did it at a fraction of the cost. And if it succeeds, it will once again prove that space doesn't have to be prohibitively expensive."

BEAM will be on the space station for a minimum of two years, where Bigelow will monitor it in order to earn NASA's approval for further human use.

"NASA is essentially the Good Housekeeping seal of approval for habitats, at this point in time," Bigelow said. "It is the prime customer that you want to satisfy. … It has a very high standard."

Stallmer said that it may also look, from the outside, as if what Bigelow Aerospace has already accomplished were simple, or that creating the habitat technology was the company's greatest challenge. But Bigelow said the number one challenge facing the company is politics.

"You have to have political permission first. You have to have the money second. If you have those two, you can create whatever technology you need," Bigelow said, perhaps referencing the company's struggles to get its Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 habitats launched.

He said that refers to politics within NASA as well as the U.S. government, and "whether or not NASA is going to be an agent for this kind of change. Or is it going to be managed by an administration whose philosophy is to thwart commercialization?

"If NASA resists, and the philosophy of our politics, of our administration, is to continue to pursue NASA as an owner instead of a consumer, instead of a tenant, if you will, then a lot of delay will occur and it won't proceed like it could have," he said. "But if NASA's philosophy is to expand commercialization, to promote it and really facilitate it — then, oh my gosh, it'll be night and day."

Editor's Note: BEAM is flying to the space station on a SpaceX Dragon cargo spacecraft, not a Cygnus spacecraft as this article previously stated.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter