Perseid meteor shower 2025: when, where and how to see it

The Perseid meteor shower is one of the best shooting star displays of the year.

The Perseid meteor shower is one of the most prolific meteor showers of the year. The shower is active from mid-July until late August and will peak on the night of Aug. 12, before dawn on Aug. 13, 2025.

Viewers should start observing around 11 p.m. local time when the rates of shooting stars increase and can watch the sky until dawn. Unfortunately, the peak occurs just three days after a full moon, so moonlight may wash out fainter meteors.

— When: July 14 to August 24

— Peak: Aug. 11-12

— Comet of origin: 109P/Swift-Tuttle

— Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR): 100

(The number of meteors a single observer would see in an hour of peak activity with a clear, dark sky and the radiant at the zenith).

Although the Perseids occur annually, there's already anticipation for a potential Perseid meteor storm in 2028, so be sure to mark your calendars!

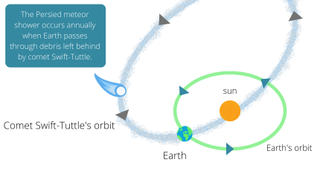

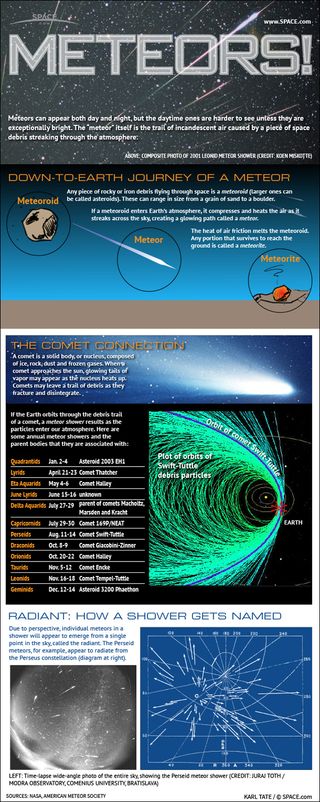

The Perseids result from Earth passing through debris — bits of ice and rock — left behind by Comet Swift-Tuttle, which last passed close to Earth in 1992.

The shower peaks around Aug. 11-13, when Earth travels through the densest and dustiest part of this debris. In years without moonlight, the meteor rate appears higher, and during outburst years (such as 2016), the rate can reach 150-200 meteors per hour.

Related: Meteor shower guide: When is the next meteor shower?

If you're looking for a good camera for meteor showers and astrophotography, our top pick is the Nikon D850. Check out our best cameras for astrophotography for more and prepare for the Perseids with our guide on how to photograph a meteor shower.

According to NASA, you can expect to see an average of up to 100 meteors per hour during the Perseid's peak.

A typical Perseid meteoroid (which is what they're called while in space) moves at 133,200 mph (214,365 kph) when it hits Earth's atmosphere (and then it is called a meteor). Most of the Perseids are tiny, about the size of a sand grain. Almost none of the fragments hit the ground, but if one does, it's called a meteorite.

The Perseids are hot stuff, reaching temperatures of more than 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,650 Celsius) as each fragment travels through the atmosphere and both compresses and heats the air in front of it. Most of the fragments are visible when they are about 60 miles (97 kilometers) from the ground.

What causes the Perseid meteor shower?

The Perseid meteor shower is caused by the comet Swift-Tuttle.

Swift-Tuttle was discovered independently by two astronomers, Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle, in 1862. When it last made a pass by Earth in 1992, it was too faint to be seen with the naked eye. The next pass, in 2126, could make it a naked-eye comet similar in brightness to the 1997 Hale-Bopp comet — providing that predictions are correct.

Comet Swift-Tuttle is the largest object known to repeatedly pass by Earth; its nucleus is about 16 miles (26 kilometers) wide. It last passed near Earth during its orbit around the sun in 1992, and the next time will be in 2126.

When you sit back to watch a meteor shower, you're actually seeing the pieces of comet debris heat up as they enter the atmosphere and burn up in a bright burst of light, streaking a vivid path across the sky as they travel at 37 miles (59 kilometers) per second, according to NASA.

Where is the Perseid meteor shower?

Right ascension: 3 hours

Declination: 45 degrees

Visible between: : Latitudes 90 and -35 degrees

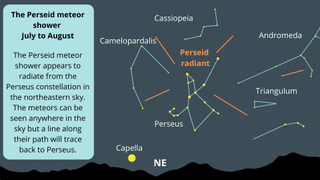

Meteor showers are named after the constellation from which the meteors appear to emanate. From Earth's perspective, the Perseids appear to come approximately from the direction of the Northern Hemisphere constellation Perseus.

You can see the Perseid meteor shower best in the Northern Hemisphere and down to the mid-southern latitudes, and all you need to catch the show is darkness, somewhere comfortable to sit and a bit of patience.

To find the Perseid meteor shower, it's a good idea to look for the point in the sky where they appear to originate from, this is known as the radiant. According to NASA, the Perseids' radiant is in the Perseus constellation. Though Perseus isn't the easiest to find, it conveniently follows the brighter and more distinctive constellation Cassiopeia across the night sky. The meteor shower gets its name from the constellation it radiates from, the constellation is not the source of the meteors.

If you take a cool photo of the Perseid meteor shower let us know! You can send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

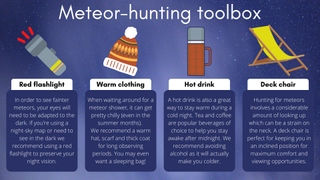

To best see the Perseids, go to the darkest possible location and lean back and relax. You don't need any telescopes or binoculars as the secret is to take in as much sky as possible and allow about 30 minutes for your eyes to adjust to the dark.

If you want more advice on how to photograph the Perseid meteor shower, check out our how to photograph meteors and meteor showers guide and if you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

When is the best time to view the Perseid meteor shower?

The best time to look for meteors is in the pre-dawn hours.

The peak viewing days are typically your best shot to see the sky speckled with bright meteors.

According to Earth Sky the mornings of Aug. 11 and Aug. 12 are the best for Perseid hunting. Though Aug. 13 may also be good, Earth Sky advises meteor hunters to remember that Perseids tend to fall off rapidly after their peak.

Skywatchers looking out for the Perseids might also be treated to some stray meteors from the southern delta Aquariid meteor shower which peaks in late July, according to AMS. Though the southern delta Aquariids are best viewed from the Southern Hemisphere, they can sometimes be visible to those in the mid-latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere.

Could Comet Swift-Tuttle collide with Earth?

An astronomer calculating Swift-Tuttle's orbit once suggested that it could come dangerously close to Earth in 2126 and possibly collide with the planet. Further refinements, however, show that the comet will not, according to a primer by the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

Swift-Tuttle's pass by Earth in the year 3044 could bring it within a million miles of our planet. That's just over twice the distance from the Earth to the moon, making the comet very close in astronomical terms.

The uncertainty came because initial projections for Swift-Tuttle's path through space came from only three months of observations in the 1860s when the comet was first discovered, added the primer's author, Sally Stephens.

In the 1970s, astronomers noted that the number of annual Perseids meteors was increasing, suggesting that the comet would make an appearance soon. "But it failed to show, and soon afterward, Perseid meteor activity dropped sharply. Astronomers wondered if the comet had somehow come and gone unnoticed," Stephens wrote.

Brian Marsden, who was an astronomer with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, suggested in 1973 that Swift-Tuttle might be the same comet as one seen in 1737 by a Jesuit missionary in China.

Marsden suggested the comet would return in 1992, which it did, but its closest approach was 17 days off from his prediction. He continued tweaking his calculations. Although he initially predicted a possible collision in 2126, he examined the historical record and found observations of a comet in a similar track as far back as at least 188 A.D. — allowing him to calculate the comet would pose no harm.

"His new calculations show Comet Swift-Tuttle will pass a comfortable 15 million miles from Earth on its next trip to the inner solar system," Stephens wrote.

Additional resources

If you're interested in learning more about Comet Swift-Tuttle check out this interesting informative image entry by ESA. The National Schools Observatory provides a great overview of meteor showers and how to plan your meteor spotting. If you're looking for a nice kid-friendly introduction to meteor showers, NASA has got you covered.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!

- Chelsea GohdSenior Writer

-

Jan Steinman Meteors! From night before last. I count five, plus an airplane. Some are curved, due to the fisheye lens I used.Reply

Olympus OM-1 with M.Zuiko 8mm ƒ/1.8 full-frame fisheye, using Live Composite, about 120 each ten-second exposures. -

paulmercurio Super cool! Just one thing though, the moon is more like a quarter of a million miles from Earth, not half, so the comet would be more like 4 times the distance from Earth to the moon in 3044 if it got that close.Reply