'Magic Islands' May Bubble to the Surface of Saturn's Moon Titan

THE WOODLANDS, Texas — Bubbling seas may create the mysterious "magic islands" of Titan, Saturn's largest moon.

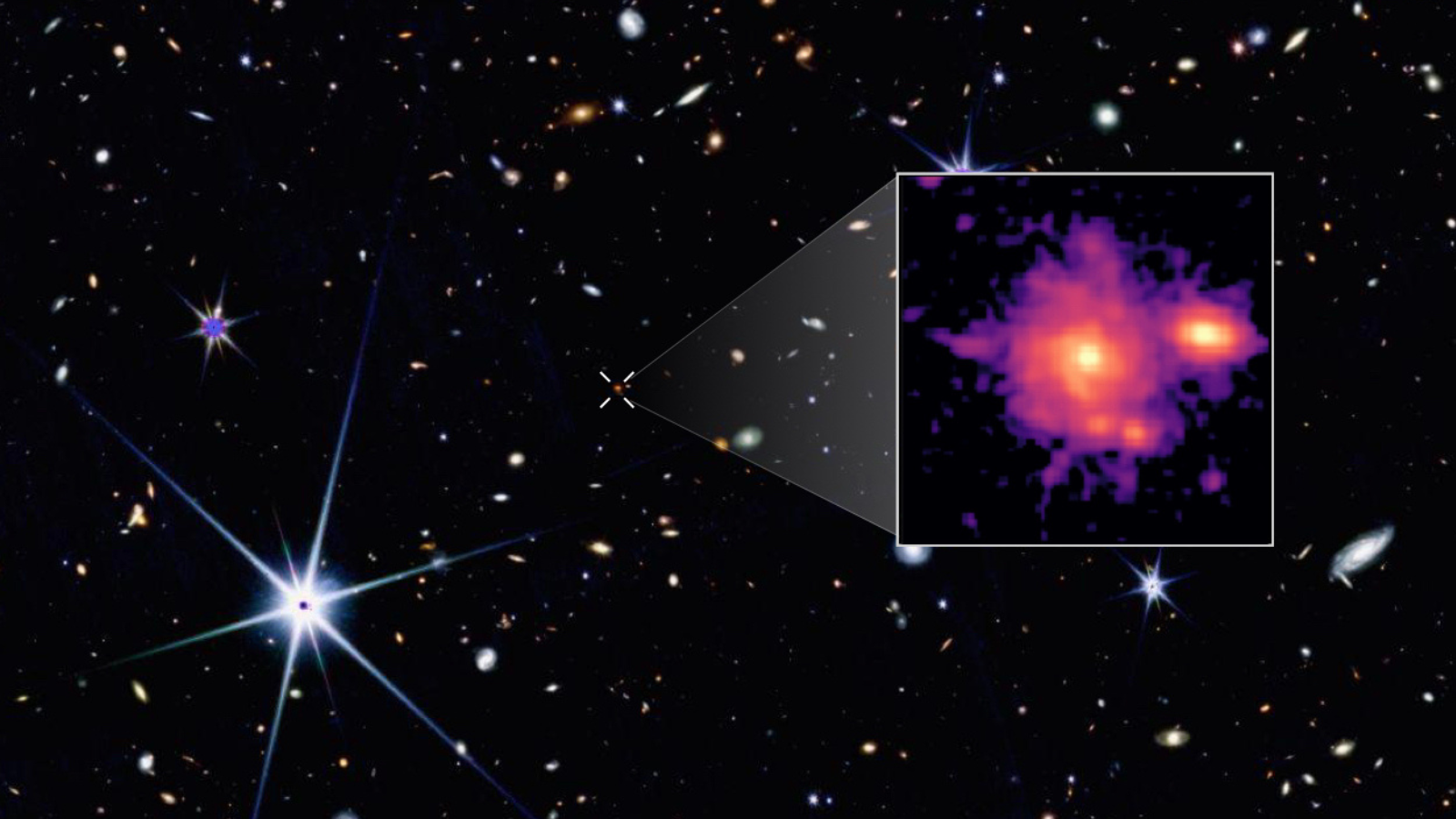

New research has revealed that mixing the most common elements found on Titan produces nitrogen bubbles. It's possible the bubbles are forming in Titan's oceans, where scientists have observed strange features that appear and disappear from satellite images — the so-called magic islands of Titan — according to Michael Malaska, a planetary scientist at of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California.

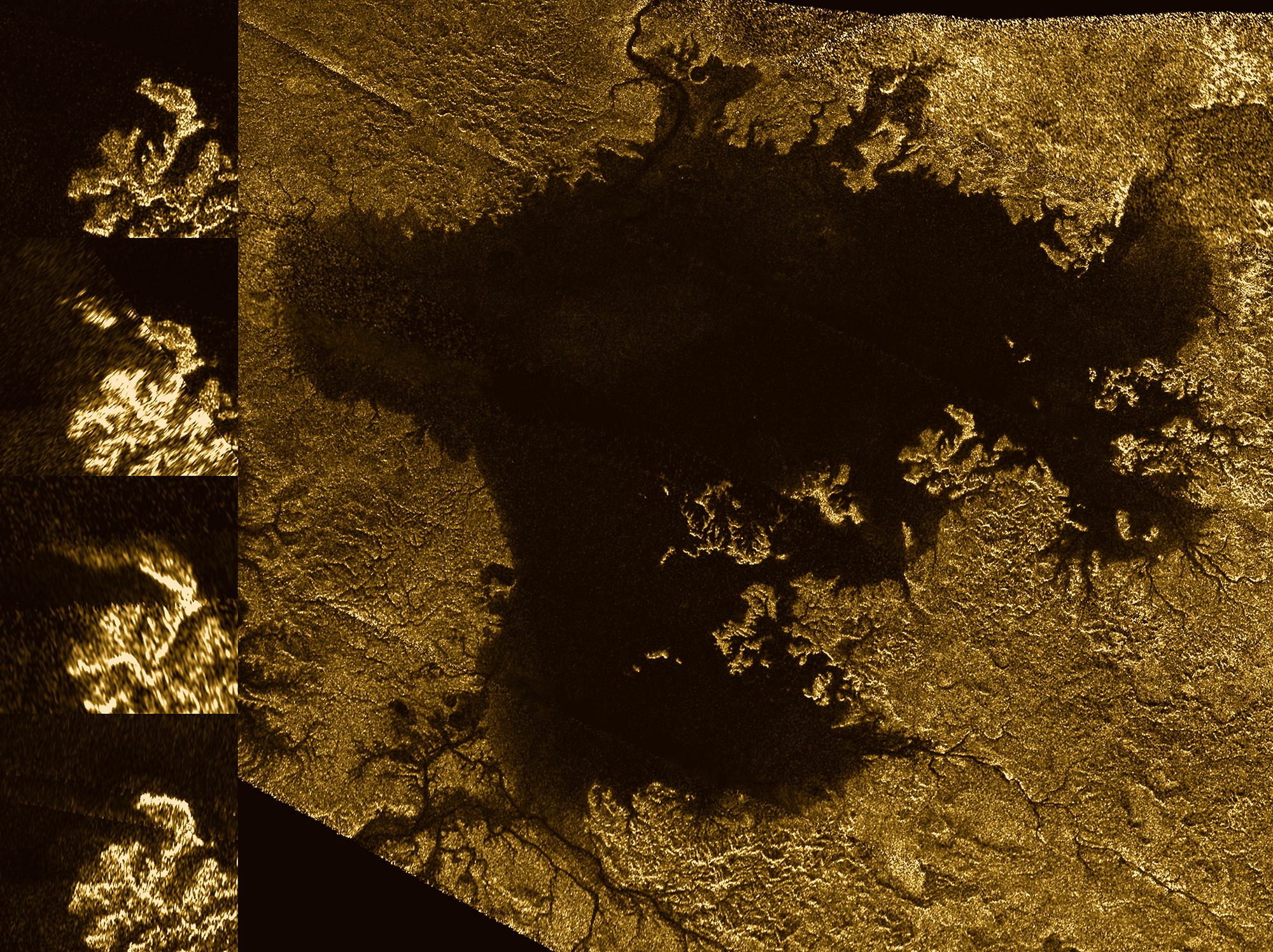

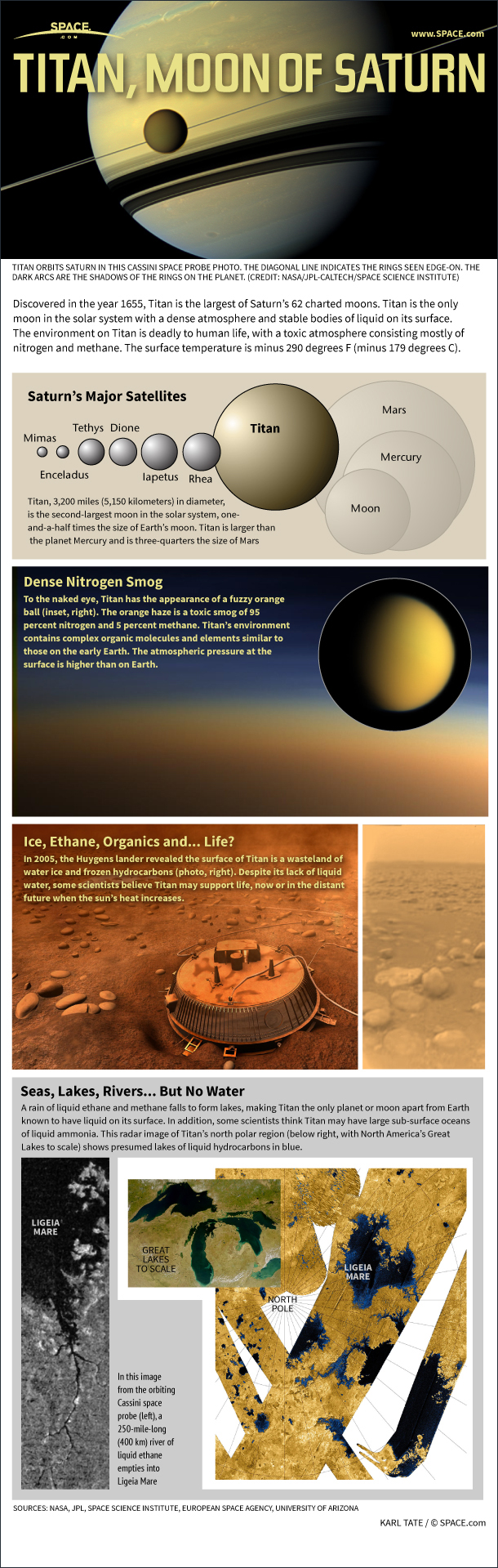

The only other world in the solar system with liquid on its surface besides Earth, Titan hosts lakes and seas of ethane and methane. The two materials should form distinct layers, but rainfall can stir them up, and the mixing releases nitrogen bubbles, the new work shows. [Amazing Photos of Saturn's Moon Titan]

"If you dump a cupful of Titan rainfall into a lake, you're going to get about 15 cupfuls of nitrogen gas," Malaska told Space.com "That's quite a large amount of bubbles."

Malaska led the team that investigated the mixing of Titan's dominant liquids in a lab on Earth, and spoke about the new research at the Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference in The Woodlands in March.

Bubbling seas

In 2013, NASA's Cassini orbiter glimpsed a feature on one of Titan's seas that hadn't been spotted in previous passes. Later glimpses of the region revealed that the object, unofficially dubbed a magic island, had disappeared again. The spacecraft detected more islands on later passes.

To help solve the mystery, Malaska and his colleagues turned to Earth-based labs. Originally, Titan was thought to host lakes and seas of pure ethane, but observations revealed that they are more methane-rich, a finding that Malaska told Space.com was "sort of a surprise." Rather than mixing, the two materials settle into layers as liquids.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Lakes and seas aren't Titan's only unusual feature; the moon also boasts methane rains. When the rain falls, it can create temporary channels that can eventually flow into the lakes and seas, Malaska said. When they reach the larger bodies, eddies can churn the liquid, mixing the methane and ethane and releasing nitrogen contained by both molecules. The nitrogen gas then rises to the surface, producing bubbles that could appear as the transient features spotted by Cassini, the new work suggests. According to Malaska, some of the magic islands appear near signs of streaming liquid, suggesting a connection.

Flowing methane isn't the only possible explanation for the bubbles. The rainfall itself could sufficiently mix the layers. As the methane falls into the ethane, the two could mix and release nitrogen bubbles.

Changes in temperature could also be responsible. As the seasons change on Titan, the temperature could rise just enough to heat the lakes and seas, breaking the nitrogen apart and letting it rise to the surface.

"If it becomes toasty in the summer, it's going to cause an amount of nitrogen to come out," Malaska said. "It may be slow enough that it's not going to have a huge massive bubble eruption, it might be able to fizz off the top, but it does mean the composition of the type of fluids are going to change with the season."

How long the bubbles sit on the surface depends on the composition of the lake. If it's pure methane, Malaska said they will pop at the surface rather than producing something similar to sea foam seen on Earth. But other compositions may allow the bubbles to stick around a little longer.

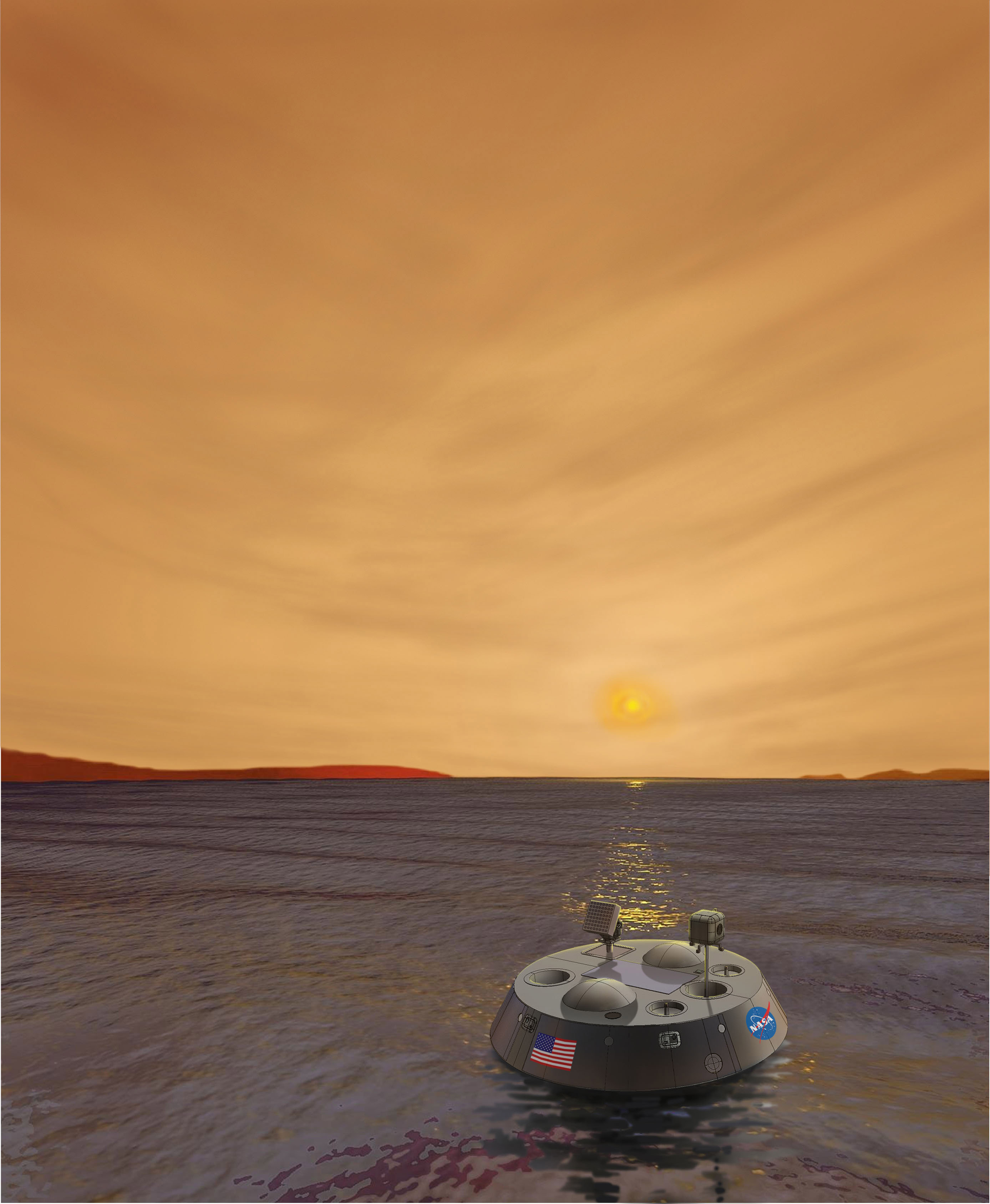

NASA is reviewing the Titan Mare Explorer (TiME), a probe that will land in the sea and float. Farther down the road, scientists are considering dropping a submarine into Titan's seas. But mission planners might need to consider whether or not a probe could cause mixing (and hence, bubbles) of the methane and ethane. In addition, energy sources powering the probe instruments, its movement and its communication systems would need to be placed above water or behind the instruments in order for the sub to avoid creating heat that could produce bubbles that might disrupt observations. Still, Malaska said he doesn't see the bubbles as a long-term problem for the future mission.

Because Cassini is flying past the moon rather than remaining in orbit, its observations are brief, making it difficult to determine how long magic islands stick around; they could last seconds or days. Previous have offered suggestions to explain the features., including waves kicked up on the seas, or by the spattering pattern of rainfall on the surface, Malaska said.

"Our lab results suggest that bubbles are a very serious contender," Malaska said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd