How 3D Printing Will 'Rock the World' — and Space

Three-dimensional printing, also called rapid prototyping, has finally started to go mainstream. Companies like MakerBot create home versions of machines that use computerized blueprints and extruded plastic to make objects, which were once limited to design firms.

In space, the ability to 3D-print parts would mean that a longer mission could avoid carrying spares, instead bringing only the raw materials. This would make repairs and experimentation much easier.

As the technology becomes more common, 3D printing will fundamentally alter the way people manufacture things, on Earth and in space, said John Hornick, an intellectual property lawyer and a partner at Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, L.L.P. Hornick recently published a book, "3D Printing Will Rock the World" (CreateSpace independent publishing platform, 2015). [3D Printing: 10 Ways It Could Transform Space Travel]

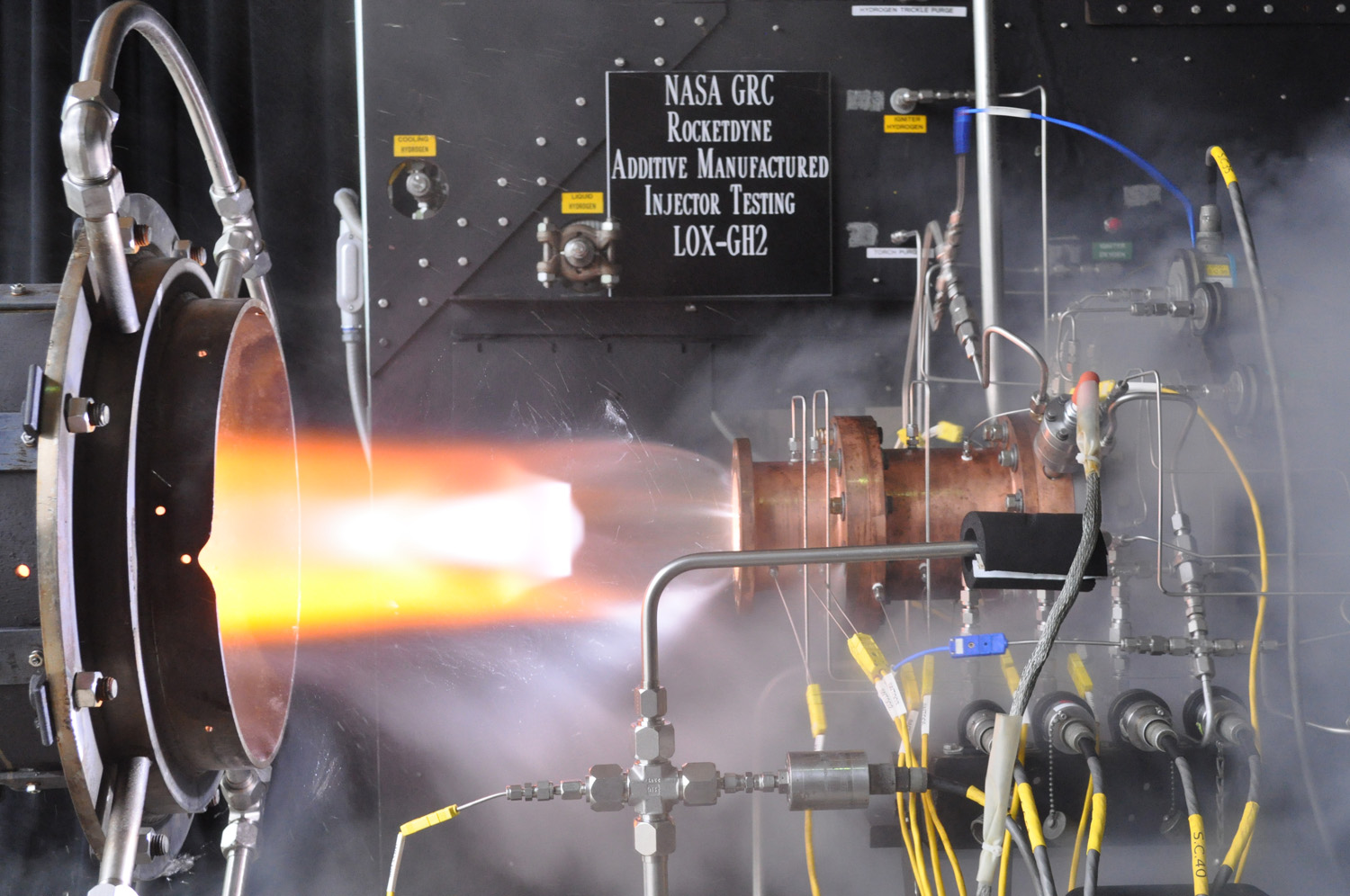

In his separate essay "3D Printing Our Way to the Stars," Hornick noted that NASA has already experimented with 3D printing. The agency emailed the blueprint for a wrench from NASA's Huntsville Operations Support Center to the space station, which has a 3D printer on board, and the wrench was successfully printed out. Made In Space, Inc., the company that designed the space station's 3D printer, said the machine could reproduce about a third of the spare parts the station needs. Meanwhile, companies like Aerojet Rocketdyne have experimented with 3D printing in metals, which could make it possible to create rocket engine parts more quickly and cheaply than with traditional methods.

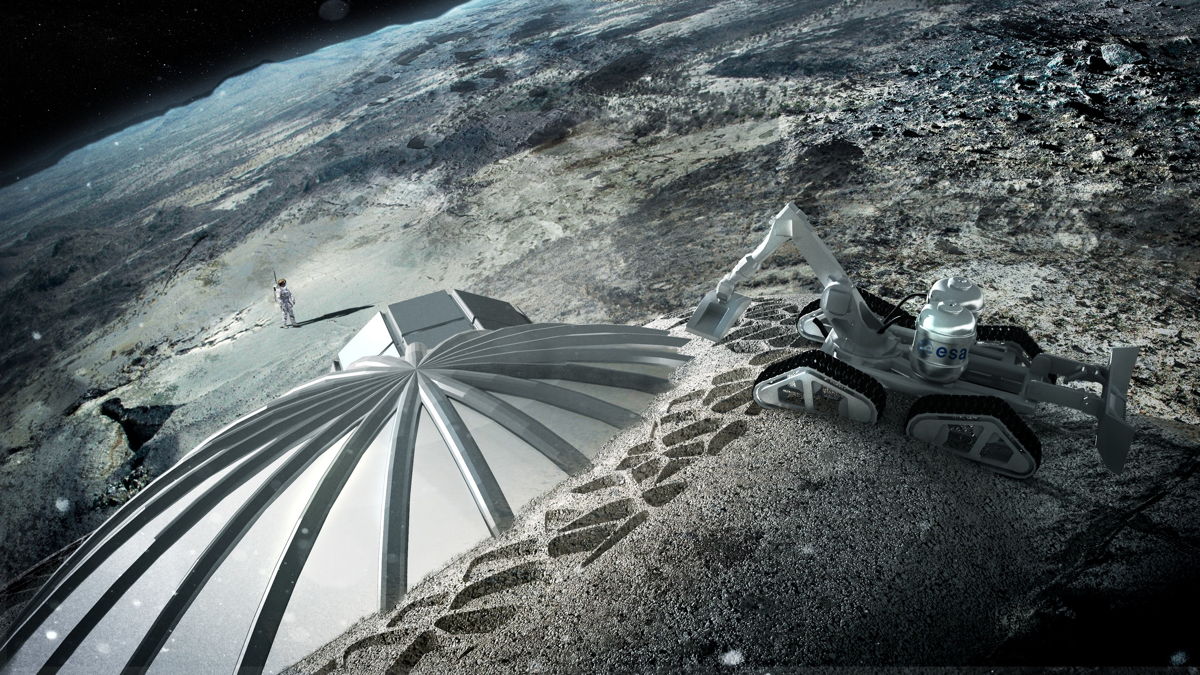

In the new book, Hornick also cited a number of advances in 3D printing that would have space applications, such as Boeing's patent application for a 3D printer that can print in any plane. Ordinarily, a 3D printer builds layer by layer, and would require some kind of gravity. Boeing's design can build layers in any orientation, and actually suspends the part, levitating it with magnetic fields or sound waves. Such a machine would allow for building parts in microgravity environments — either in Earth orbit or on a trip to Mars.

Space.com talked with Hornick about his book and the future of 3D printing.

Space.com: What do you want people to take away from your book?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

John Hornick: It's kind of a book to educate people on where the technology is now. The general public believes 3D printers are machines that make Yoda heads. I also want to educate industry [about 3D printing], that it's far enough along that they should consider it, how it can help them or how it can hurt.

Space.com: How did you come to write the book?

Hornick: The way I got into this several years ago was a friend sent a video of a machine printing out a wrench. I thought, "This is a joke." But it wasn't. Then at Johns Hopkins [University in Baltimore], they said people were working on printing human organs.

The press articles kept saying it presents a lot of intellectual property issues, but they never said what. I'm an intellectual property attorney, so I said, "I am going to figure out what they are." I started looking to see what work [our firm] had done in this space, and I decided to formalize that practice. I created a database. There was so much information and so much happening, I wanted it at my fingertips. I thought I really had enough information for a book, and my interest was way beyond the law. In some ways, it wrote itself.

Space.com: You foresee a golden age of distributed manufacturing?

Hornick: I think it's coming. We're starting to see distributed manufacturing. Right now in the 3D printing industry [there] are these small businesses — some are traditional machine shops with 3D printers. A lot of their customers are local. There are already hundreds of these around the United States. We've had these shops for years, but most were doing rapid prototyping. As the technology gets more sophisticated, you might have something like a UPS store. [UPS announced it would offer 3D printing services in 2014.] [UPS is] big into industrial capabilities in retail locations. I think you might have some things in the home, some on the internet and some down the street. There's no reason to think the technology won't improve over time.

Whether we have that, it depends on how corporations decide they want to deliver things to us, if they want to continue to make things in a factory or if they can farm it out to customers.

Space.com: You say in the book that people have a natural tendency to make things. But wood shops are available to millions of people, and most people don't make tables and chairs. How do you reconcile this?

Hornick: I'm a woodworker and I do make furniture. One limiting factor is need. I haven't had a project in the wood shop for a while, because I don't need anything. There are people who might use it regularly or only for cutting a board that you need. 3D printing is different. There, you have the ability to make things that you need.

If you need a replacement part for something in your house and you can print that out, or print some kitchen device that you want just by hitting download and hitting print — or a product that you can customize — there may be people who might build that way. It all depends on how deeply the technology wiggles its way into our lives and how easy it is to use.

Space.com: In your book you say that innovations in 3D printing could make a big difference in space, and you cite Boeing's development of a printer that works in several orientations, without the need for a single flat platform. Wouldn't you need to carry the raw materials with you?

Hornick: Yes, 3D printing in space requires having the right materials handy, and in sufficient quantity. With increasingly versatile machines and materials, it would not be necessary to stock every material under the sun (or moon). And stocking basic materials to 3D-print replacement parts (and getting them into space) would be easier than stocking every spare part that may be needed.

Space.com: Do you see something like a Star Trek replicator? That would mean control of materials at the molecular scale.

Hornick: Not quite like that. What I often say is something from Bill Gates — we overestimate what we can do in two years and underestimate what we can do in 10 years. Very versatile machines that can make a wide range of parts in the home and business as well, that's doable. 3D printing isn't new, where nobody has a use for it yet. The technology has been around for 30 years, and it's not going to go away. The question is how much more ubiquitous it's going to be. I just think it's impractical to think it won't get faster and easier over time.

Right now, people think of 3D printing as layer by layer. But there are some new processes that take that and they change it. Disney had a patent application [filed in April 2016]. They had a machine that makes a whole part in a vat of photopolymer, curing it [heat treating it to set the plastic] as a whole part at once.

Space.com: What about intellectual property? What are some of the issues in a world where one can duplicate products?

Hornick: There are some startups working on this problem. Some want to create a digital kernel, embedded in the system specifications and maybe even the materials. Yes, [widespread 3D printing] could lead to total product anarchy. That's a real concern. But I'm anxious to see the market solutions. I think the market will come up with solutions to the problem.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.