The Universe's First Galaxies May Light Up Its Dark Ages

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

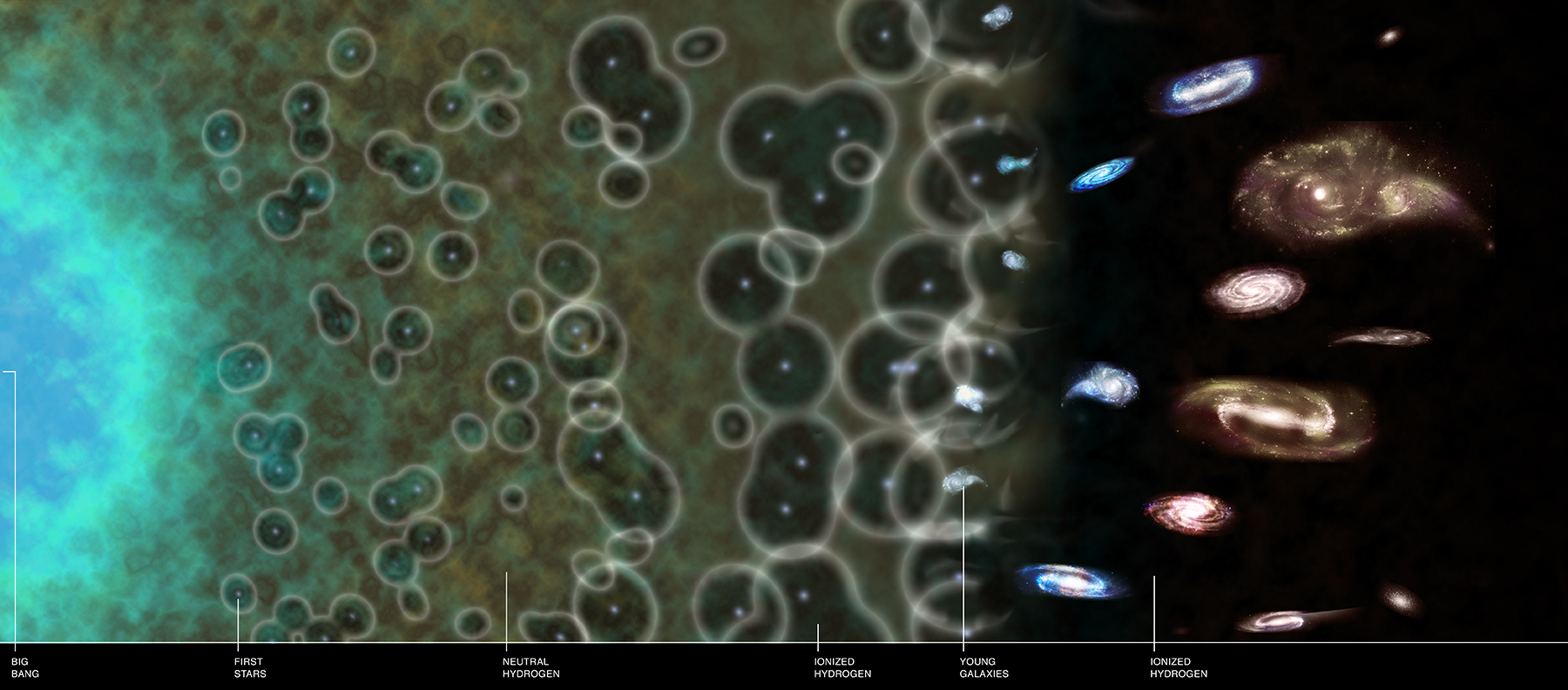

A collection of newfound galaxies is illuminating how the early universe broke free from its Dark Ages. The family of galaxies may have played a role in the shift from a time when some light could not penetrate to an era of a transparent universe.

"Stars and black holes in the earliest, brightest galaxies must have pumped out so much ultraviolet light that they quickly broke up hydrogen atoms in the surrounding universe," David Sobral, an astrophysicist at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. Sobral led an international team of scientists aiming to find several of these early galaxies using the Subaru and Keck telescopes in Hawaii and the Very Large Telescope in Chile. The results were presented today (Monday, June 27) at the National Astronomy Meeting in Nottingham, England.

"The fainter galaxies seem to have stayed shrouded for a lot longer," he said. "Even when they eventually become visible, they show evidence of plenty of opaque material still in place around them." [The Universe: Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

In 2015, Sobral led a team that found the first two members of the collection, galaxies CR7 and MASOSA, which might contain the first generation of stars. Together with a third galaxy known as Himiko, discovered by a Japanese team, the presence of the trio of galaxies hinted that a large population of similar objects might exist.

The problem, however, is in spotting them. About 150 million years after the Big Bang kicked off the universe's existence (an event that took place 13.8 billion years ago), the universe was dense with neutral hydrogen that blocked the passage of certain wavelengths of light. As radiation from the earliest stars split apart hydrogen in what scientists call the "epoch of reionization," light began to slowly pass through the surroundings, bringing the Dark Ages to an end.

Each of the five newfound galaxies discussed in the presentation contains a large bubble of ionized (charged) gas around them, suggesting that they haven't managed to completely break free from the Dark Ages.

"Our results highlight how hard it is to study the small, faint sources in the early universe," said co-author Sergio Santos, a graduate student at Lancaster University.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The neutral hydrogen gas blocks out some of their light, and because they are not capable of building their own local bubbles as quickly as the bright galaxies, they are much harder to detect," he said.

The fifth of the faraway sources discovered, VR7, is named in tribute to astrophysicist Vera Rubin, who won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1996, becoming the first woman to win that award in over 150 years.

The young galaxies may be just a handful among the hundreds of thousands of ancient galaxies that might be spotted by future instruments.

"What is really surprising is that the galaxies we find are much more numerous than people assumed, and they have a puzzling diversity," Sobral said. "When telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope are up and running, we will be able to take a closer look at these intriguing objects."

"We have only scratched the surface, and so the next few years will certainly bring fantastic new discoveries," he said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky