Target Mars: Red Planet in World's Crosshairs

The robots currently circling Mars and rolling across its surface are about to get a lot of company.

A number of different public and private organizations — from NASA, to the European Space Agency (ESA), to Elon Musk's ambitious company SpaceX — plan to launch missions to Mars in the near future.

Some of these projects will probe the Red Planet's structure and composition, while others will hunt for signs of life. And the increased focus on the Red Planet and its biological potential could ratchet up other such efforts, some experts say. [The Life on Mars Search: A Photo Timeline]

Mars-bound

The international Mars exploration agenda is pretty packed for the next few years. Here's a rundown:

China: Chinese space officials have plans to send a rover to the Red Planet as early as 2020, and are also working to stage a mission that would collect samples of Mars for return to Earth around 2030.

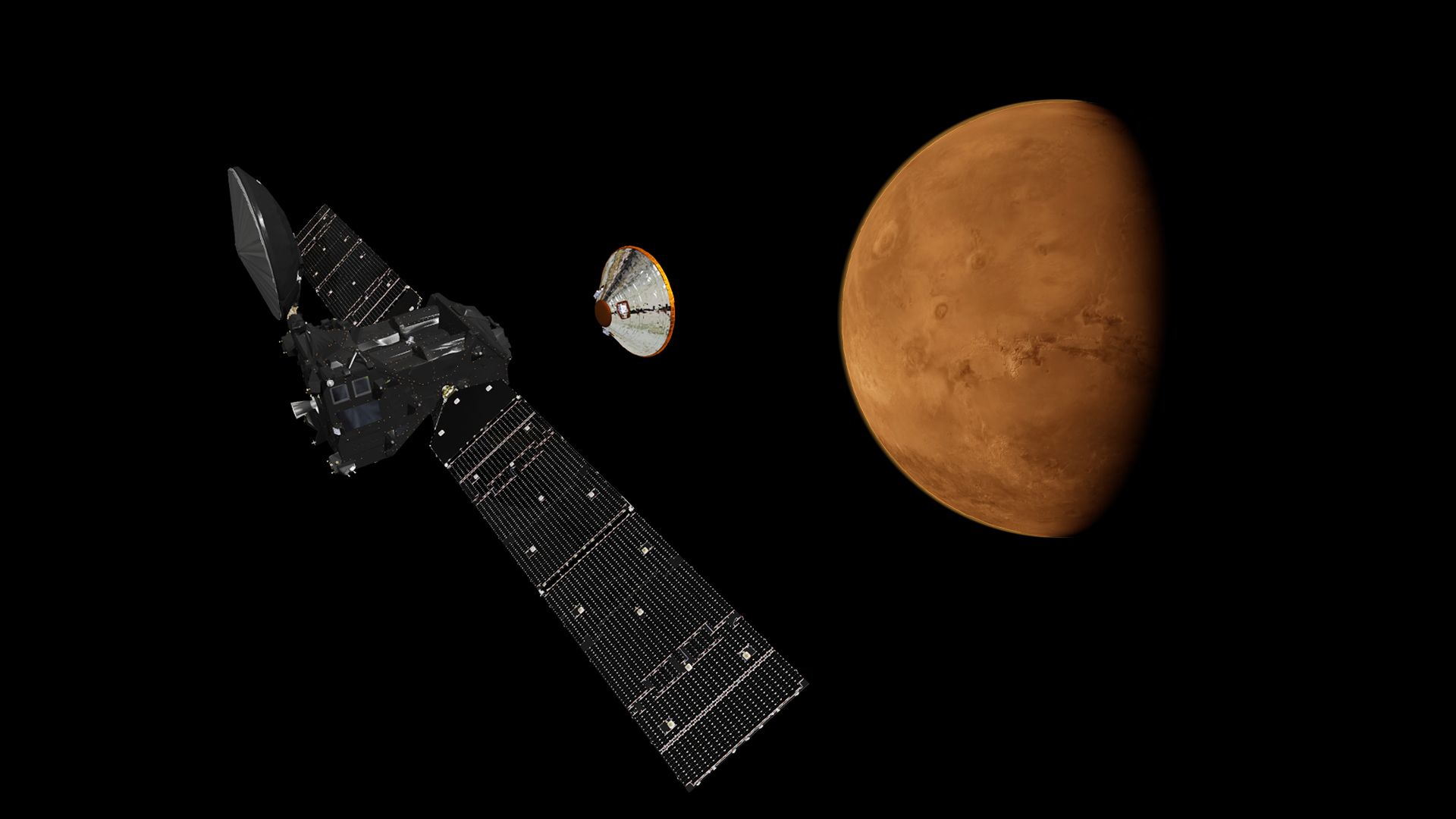

Europe: ESA and Russia are teaming up on the two-phase, life-hunting ExoMars program. The first phase — which consists of a methane-sniffing orbiter plus an entry, descent and landing demonstrator module — will arrive at the Red Planet this coming October. The second phase will launch a drill-equipped rover in 2020, if current schedules hold.

India: India's Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) spacecraft, also known as Mangalyaan, swung into orbit around the Red Planet in September 2014. NASA and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) have formed a joint working group to investigate enhanced cooperation between the two countries in Mars exploration.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Japan: The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) is thinking about launching a sample-return mission to one of Mars' two tiny moons, Phobos and Deimos. The selected moon would be targeted for a landing in the early 2020s.

United Arab Emirates: The UAE is building a Mars orbiter that Japan would launch in 2020 to search for connections between current weather and the planet's ancient climate.

United States: NASA plans to launch its InSight (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) lander in 2018 and then loft the Mars 2020 rover two years later to look for signs of past life. The space agency also aims to launch a multifunctional, next-generation orbiter toward the Red Planet in the 2020s.

SpaceX: Musk has said that SpaceX plans to launch an uncrewed Dragon spacecraft toward Mars as soon as 2018, to help pave the way for an astronaut touchdown in 2025. [SpaceX's Red Dragon: A Private Mars Mission Plan in Pictures]

Trying to get on the map

"I can just see each country trying to figure out what they can do that is going to really put them on the map," said Ben Clark, a senior research scientist at the Space Science Institute (SSI) in Boulder, Colorado. "That would be, of course, discovering life on Mars." (Clark has had a long association with Mars stemming back to the U.S. Viking lander missions in the 1970s.)

Indeed, some nations may see Mars missions as a way to gain prominence on the global stage.

"In my view, Mars draws interest both for its potential as an abode for Martian microbes and for humans, and also as a status symbol for emerging spacefaring nations," said Steven Ruff, associate research professor at the Mars Space Flight Facility in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University.

Different objectives

But not all of these countries have the same goals for their Red Planet missions; some are interested in searching for life, while others are not. "My sense is that there's not a universal effort among all the Mars-bound parties to find life," Ruff said.

For example, detecting extant Mars life is not the chief focus of any of NASA's upcoming Red Planet missions, Clark said (though the 2020 rover will hunt for past life).

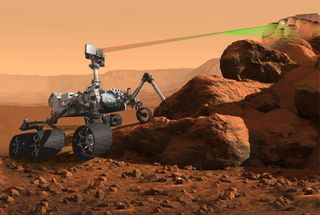

"The 2020 ExoMars rover mission of Europe is, however, proclaiming they want to find evidence of life," Clark told Space.com. That rover will tote a drill that can reach more than 7 feet (2.1 meters) below the Martian surface.

India's Mangalyaan is already hunting for methane from orbit, hoping to spot surges of this gas — a possible sign of life — before other spacecraft do so, Clark said.

The ExoMars orbiter that's currently on its way to the Red Planet will do similar work, hunting for methane and other potential "biosignature" gases. The ExoMars rover, meanwhile, will take the search to the Martian surface — and the subsurface — when it touches down more than four years from now. [Launch Photos: Europe's ExoMars 2016 Mission Rockets Toward the Red Planet]

"The ExoMars rover will be in an excellent position to provide good results regarding the possible existence of life on early Mars," said ESA's Rolf de Groot, head of the Robotic Exploration Coordination Office at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, Netherlands.

The ExoMars rover will be more of a dedicated life hunter than the other missions scheduled to reach the Red Planet at about the same time, de Groot said.

"The Chinese mission is less well defined, but also does not seem to be fully dedicated to life seeking," de Groot told Space.com. "The UAE mission is an orbiter for which the main objectives seem to be technical and human capacity building and inspiration. The commercial initiatives to fly Mars missions seem to be more aimed at enabling future manned missions than at the scientific search for evidence of life."

But China may end up getting into the Mars life hunt in earnest, Clark said.

"The Chinese are very good in biotech, and could easily field experiments of the type we tried on Viking," he said.

A race to find Mars life?

So does all of this activity mean that a race to find Mars life is underway? De Groot doesn't think so.

"We never think of it in these terms," he said. "Mars exploration is becoming a truly international endeavor. While mostly dominated by NASA in the period until the early 2000s, we now see several spacefaring nations/agencies with successful or planned Mars missions … often building on the results of previous Mars missions."

James Garvin, chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, voiced similar sentiments.

"Science is never really a race," Garvin told Space.com. "The quest for understanding moves forward in fits and starts, as discoveries are made."

The set of interconnected measurements, experiments, observations and vantage points, he added, "does not suggest a 'race' but rather a concerted effort to understand so that the more ambitious and challenging big questions can be asked … such as, 'Are we alone at Mars?'"

The Mars life hunt is not a race but rather "an expression of world interest in the Martian frontier as a place to extend our imaginations and engineering capabilities to 'conquer,' so that we can understand how to search for life in the most accessible place we have available," Garvin said.

However, ESA's commitment to the search for extant life with its 2020 rover mission could signal that a competition is afoot, Ruff said.

ESA may believe that such a strategy "will deliver more quickly than sample-return [missions] and the search for dead bugs … so maybe they are racing," he said.

But "if it's a race, the contestants are pretty relaxed about racing," Chris McKay, a space scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in California, told Space.com.

A Nobel Prize for Elon Musk?

State-run agencies aren't the only ones "competing" on the Red Planet stage. Private companies, such as Musk's SpaceX, also plan to launch Mars missions.

It's not clear how the search for life on Mars fits into Musk's worldview, McKay said.

It "could be only to assess the biohazard for astronaut Musk ... or could be to win a science Nobel Prize for Iron Man," McKay said. (The movie version of Tony Stark — the fictional billionaire industrialist who invented and wears the Iron Man suit — is based partly on Musk.) "Or could be [to] get NASA to put a payload on his Red Dragon and be a paying customer."

But McKay's focus in the search for extraterrestrial life lies beyond Mars; he's looking out to an intriguing, ocean-harboring moon of Saturn.

"I'm not holding my breath, and instead I am aiming for Enceladus," McKay said. "Mars can wait."

Leonard David is the author of "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet," to be published by National Geographic this October. The book is a companion to the National Geographic Channel six-part series coming in November. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.