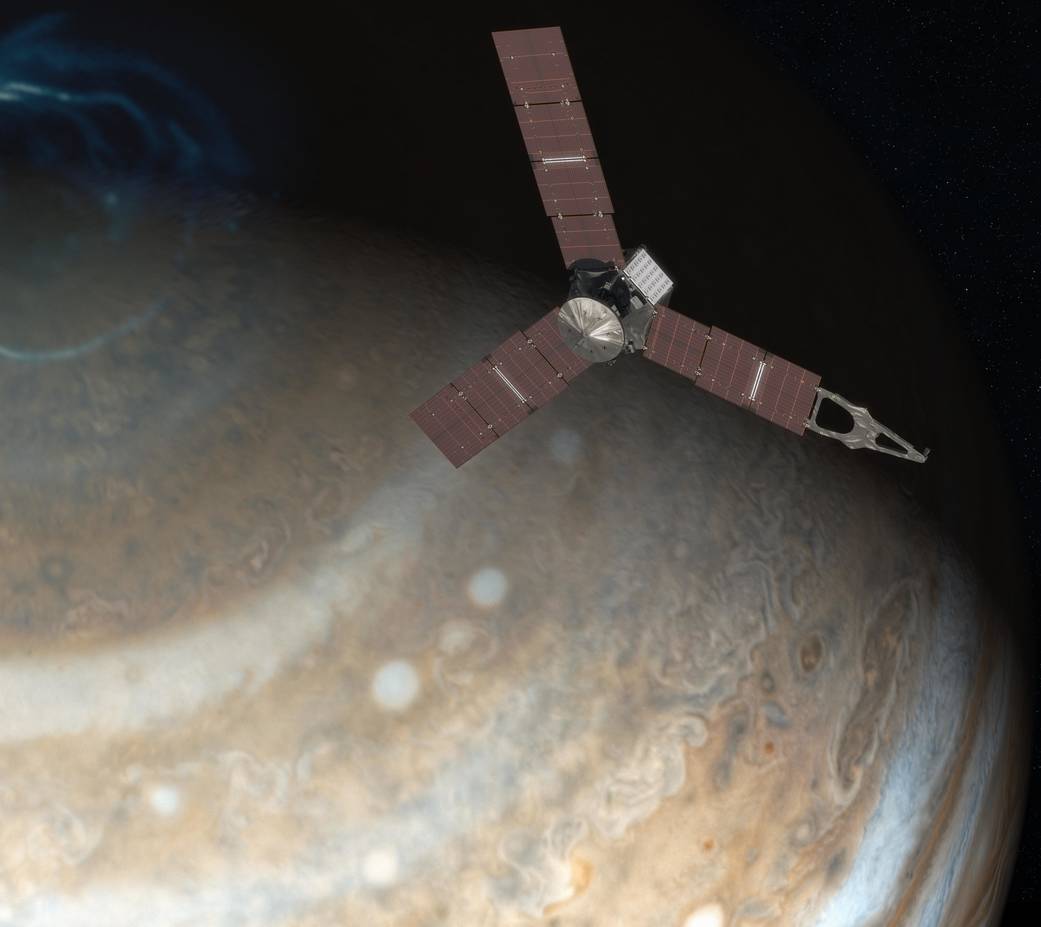

The Juno spacecraft's long-awaited arrival at Jupiter Monday (July 4) will be a baptism by fire.

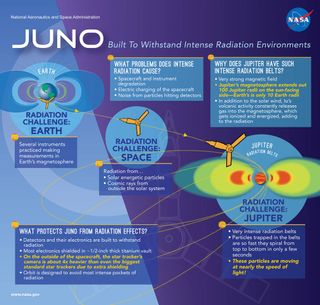

If all goes according to plan Monday night, Juno will slip into orbit around the giant planet and get its first taste of the solar system's most intense radiation environment — a region where huge swarms of electrons are accelerated to nearly the speed of light by Jupiter's magnetic field, which is 20,000 times more powerful than Earth's.

"Once these electrons hit a spacecraft, they immediately begin to ricochet and release energy, creating secondary photons and particles, which then ricochet," Heidi Becker, leader of Juno’s radiation-monitoring team, said during a news conference last month. "It's like a spray of radiation bullets." [Juno's Plunge Into Jupiter Orbit Fraught With Danger (Video)]

Juno must endure this potentially damaging barrage not just Monday night, but for the next year and a half or so: The mission plan calls for the probe to orbit Jupiter 37 times before ending its life with an intentional death dive into the planet's thick atmosphere in February 2018. (This final maneuver is designed to ensure that Juno never contaminates the potentially life-harboring Jovian moon Europa with any microbes from Earth).

So the Juno team has taken a number of steps to minimize the probe's radiation exposure.

Take the spacecraft's 14-day science orbit, for example. Juno will zoom within 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) of Jupiter at closest approach and get all the way out beyond the orbit of the moon Callisto at its most distant point. (Callisto lies about 1.17 million miles, or 1.88 million km, from Jupiter.)

This extremely elliptical orbit will allow Juno to dip under, and get beyond, Jupiter's intense radiation belts for much of its time at the gas giant, mission team members have said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But this orbit would still expose an unprotected probe to a radiation dose of more than 20 million rads — the equivalent of more than 100 million dental X rays — over the course of its mission, Becker said. So the team has outfitted Juno with a "suit of armor" to lower the dose.

The core of that suit is a nearly 400-lb. (180 kilograms) titanium vault with 0.5-inch-thick (1.75 centimeters) walls, which houses Juno's main computer and the sensitive electronic components of many of its nine scientific instruments. Radiation doses inside the vault should be 800 times lower than those experienced outside, Becker said.

Furthermore, the outer parts of Juno's scientific instruments are wearing "bulletproof vests," and the probe's star-tracking camera is protected as well. In fact, this camera — which takes photos that Juno uses to navigate — is the mostly heavily shielded object aboard the spacecraft, Becker said.

"Without that protection, the noise from the penetrating radiation would be too high to see stars, and Juno would never know where it was pointing," Becker said.

Still, some of the fast-moving electrons will doubtless get through the camera's shielding. Indeed, the Juno team will characterize Jupiter's radiation environment in part by studying the noise in the probe's photos, Becker said. (Juno does not carry an instrument dedicated to measuring the fast-moving electrons in Jupiter's neighborhood.)

This radiation work will be a sidelight for Juno, which is mainly concerned with mapping Jupiter's gravitational and magnetic fields and determining the composition and interior structure of the gas giant.

Juno scientists are particularly interested in figuring out how much water Jupiter's atmosphere contains and whether or not the planet has a core. Such data will reveal a great deal about how, when and where Jupiter formed, mission team members have said.

The Juno team is confident that the precautions they've taken will keep the spacecraft safe long enough for the $1.1 billion mission to meet its science goals. But there are no guarantees, because Juno is flying into the unknown.

"Jupiter has the scariest radiation environment of any planet in the solar system," Becker said. "It's the harshest, it's the most intense and it hasn't been fully explored yet — and it hasn't been fully explored where we're going."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.