How Often do Meteorites Hit the Earth?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Pieces of natural space debris — typically rocky shards of comets or asteroids — occasionally survive their journeys through Earth's atmosphere and strike the ground, but how often does an event like this actually occur?

While large impacts are fairly rare, thousands of tiny pieces of space rock, called meteorites, hit the ground each year. However, the majority of these events are unpredictable and go unnoticed, as they land in vast swathes of uninhabited forest or in the open waters of the ocean, Bill Cooke and Althea Moorhead of NASA's Meteoroid Environments Office told Space.com.

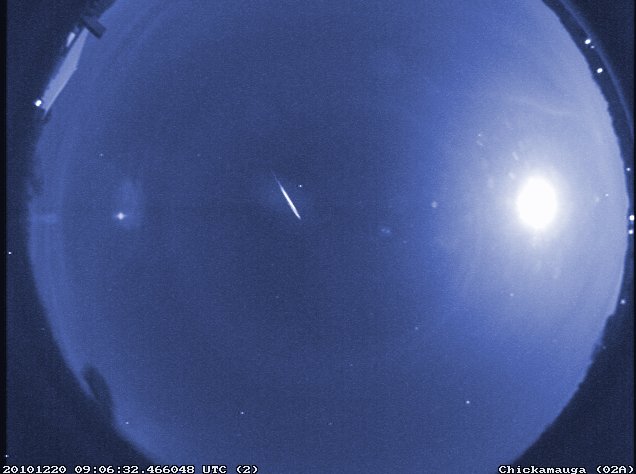

In order to understand meteorite impacts on Earth, it is important to know where the chunks of rock come from. Meteoroids are rocky remnants of a comet or asteroid that travel in outer space, but when these objects enter Earth's atmosphere, they are considered meteors. [Photos: Fireball Drops Meteorites on California]

Most (between 90 and 95 percent) of these meteors completely burn up in the atmosphere, resulting in a bright streak that can be seen across the night sky, Moorhead said. However, when meteors survive their high-speed plunge toward Earth and drop to the ground, they are called meteorites.

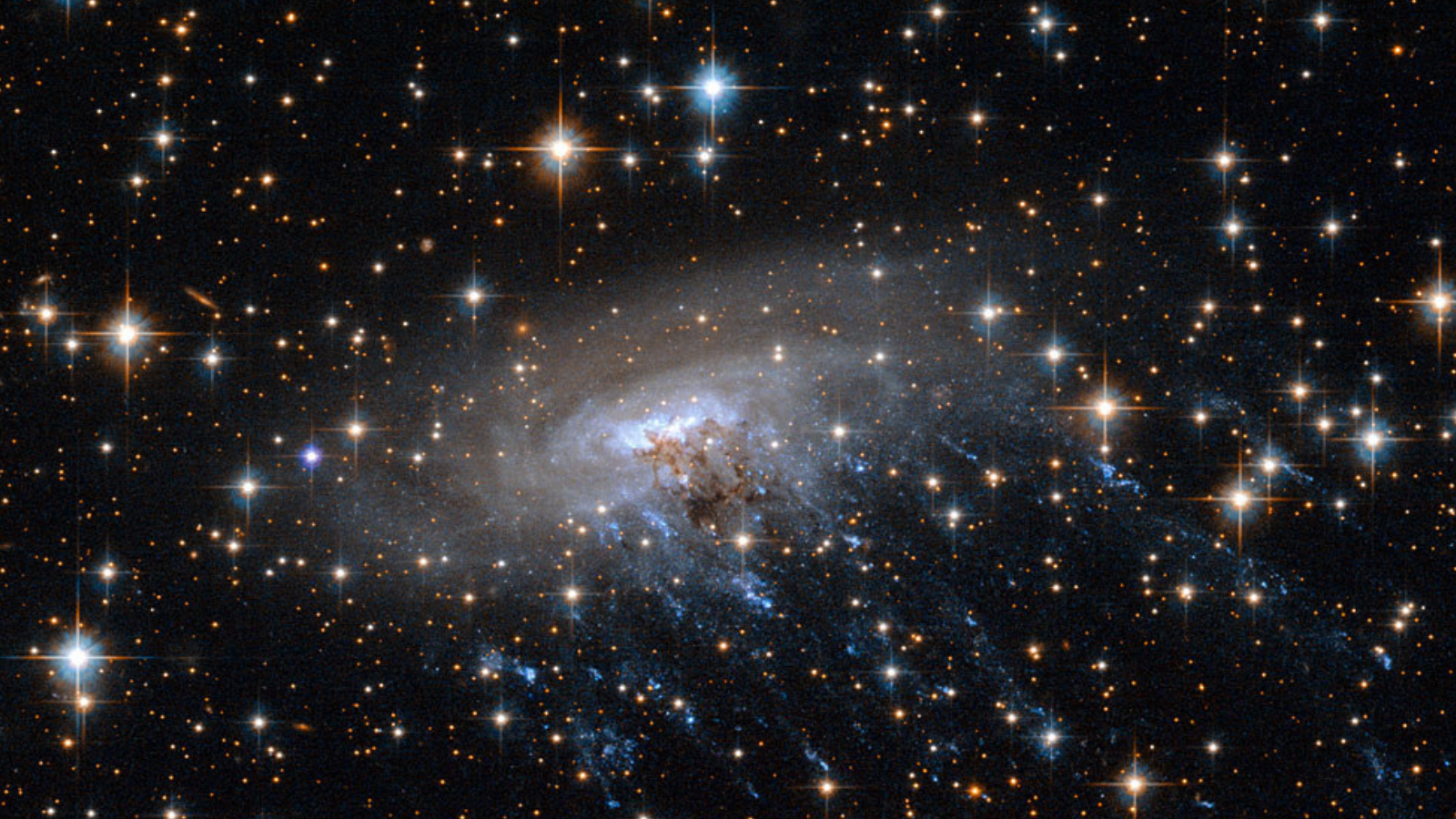

The Perseid meteor shower — one of the most popular meteor showers of the year — is expected to put on a particularly breathtaking show Aug. 11 and 12, when the Earth passes through the trail of debris created by Comet Swift-Tuttle. However, viewers should not expect to find any meteorites lying on the ground after this spectacular meteor shower.

"Perseids come from Comet Swift-Tuttle and are very fragile, being an ice-dust mix," Cooke said. "They are not strong enough to survive passage through the atmosphere at 132,000 mph (212,433 km/h) and so never produce meteorites — they are totally vaporized by the time they make it to 50 miles (80 km) altitude." [Perseid Meteor Shower 2016: When & How to See It]

Unpredictable catastrophes

Most meteorites that are found on the ground weigh less than a pound. While it may seem like these tiny pieces of rock wouldn't do much damage, a 1-lb. (0.45 kilograms) meteorite traveling upward of 200 mph (322 km/h) can fall through the roof of a house or shatter a car windshield.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

When the Grimsby meteorite landed in Ontario, Canada in 2009, for example, it broke the windshield of an SUV. In another incident, meteorites crashed into the back end of a Chevy Malibu in Peekskill, New York, in 1992, Cooke and Moorhead said. Thankfully, no one was injured during these events.

However, the pieces of rock falling from the sky are not even the greatest concern regarding meteor impacts, Cooke said.

"What causes the most damage is the shock wave produced by the meteor when it breaks apart in [Earth's] atmosphere," Cooke said. "So, you don't have to watch for the falling rocks — you have to worry about the shockwave."

For example, the Chelyabinsk meteor — an asteroid the size of a six-story building that entered Earth's atmosphere in February 2013 over Russia — broke apart 15 miles (24 km) above the ground and generated a shock wave equivalent to a 500-kiloton explosion, Cooke said. It injured 1,600 people.

Another major collision was the Tunguska meteorite, which was larger than Chelyabinsk and 10 times more energetic. The meteorite exploded over the Tunguska River on June 30, 1908, and flattened 500,000 acres (2,000 square km) of uninhabited forest. Because of its remote location, the event is an example of a meteorite that would have gone undetected had it not been so large, Cooke and Moorhead explained.

Generally, astronomers are unable to predict meteorite impacts, largely because meteoroids traveling in outer space are too small to detect. However, even large meteorite events that originate from asteroids, which can be tracked in space, are unpredictable.

Fortunately, between 90 and 95 percent of meteors don't survive the fall through the Earth's atmosphere to produce meteorites, Moorhead explained. This is because most meteorites are believed to come from comets, which are more fragile than asteroids.

"Only those meteoroids that happen to be made of stronger material produce meteorites," she said. For example, "if the [meteoroid] is a chunk of an asteroid, instead of a chunk of a comet, it's likely to be a little denser, a little stronger and more likely to produce a meteorite."

Also, if the meteor is approaching Earth at a slower speed, the rock will likely survive its collision with Earth's atmosphere, Moorhead added. In other words, the meteor will not burn up completely, and some remnant meteorites will fall to the ground.

"We actually get a few meteorites from the moon and Mars," Moorhead said. "These [meteorites] are actually chucks of the moon and Mars that have been blown off those planets by impacts and then spent a long time in space before finally hitting Earth as a meteorite."

Although predicting these events is nearly impossible, there are a couple different ways in which researchers can measure how many meteorites fall to the Earth. For example, in uninhabited areas like the Sahara Desert or atop glaciers in Antarctica, it is fairly easy to find meteorites on the ground and date them based on the amount of weathering they've experienced, Moorhead explained. Because these areas are largely undisturbed, the meteorites that lie there provide scientists with a general idea of how many of the space rocks might have hit the Earth over a period of time.

While skywatchers will not be able to hunt for meteorites after this week's Perseids meteor shower, the dazzling trail left behind by Comet Swift-Tuttle will provide spectacular light show, which can best be seen in clear skies of the Northern Hemisphere on the nights of Aug. 11 and 12.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.