Perseid Lore: The Legend and Science Behind the Epic Meteor Shower

Every August, just when many people go vacationing in rural areas where skies are dark, the famous Perseid meteor shower makes its appearance. The meteor shower peaks overnight tonight and early Friday (Aug. 11-12).

August is also the month of "The Tears of St. Lawrence."

Laurentius, a Christian deacon, is said to have been martyred by the Romans in A. D. 258 on an outdoor iron grill. In the midst of this torture, Laurentius was said to have cried out, "I am already roasted on one side and, if thou wouldst have me well cooked, it is time to turn me on the other." [Perseid Meteor Shower 2016: When, Where & How to See It]

Regardless of whether this actually happened (some believe that the story is a product of morbid medieval imagination), King Phillip II of Spain certainly believed it: He built his monastery palace, known as "El Escorial," based on the floor plan of the holy gridiron. St. Lawrence's death is commemorated every year on his feast day (Aug. 10).

To this day, the glorious Perseids — which peak every year between approximately Aug. 8 and Aug. 14 — are referred to as St. Lawrence's "fiery tears."

You can watch the Perseid meteor shower online via a free live webcast by the Slooh Community Observatory. The four-hour webcast begins at 8 p.m. EDT (0000 GMT). You can also watch the Perseids meteor shower webcast on Space.com, courtesy of Slooh.

But the earliest record of Perseid meteor activity goes back more than two centuries before the martyrdom of St. Lawrence: Chinese records from A.D. 36 state that "more than 100 meteors flew thither in the morning."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Today, we know that those fiery darts of light are actually the result of Earth's annual interaction with the dross left behind by a cosmic litterbug — a comet.

Swift-Tuttle: Mother of all Perseids

On the night of July 15, 1862, an obscure amateur astronomer named Lewis Swift was scanning the sky with his 4.5-inch (11.4 centimeters) Fitz refractor telescope from rural Marathon, New York. In a matter of minutes, Swift ran across an object in the dim constellation of Camelopardalis, the Giraffe, which he believed to be Comet Schmidt, which had been discovered only a couple of weeks earlier. [Perseid Meteor Shower 2016: Sky Maps Guide (Gallery)]

Swift made no formal announcement of his discovery — until astronomer Horace Tuttle of Harvard College Observatory independently found the same object three nights later. But that object, it turned out, was not Comet Schmidt, but a totally new specimen. The two men shared the discovery, and the comet therefore received both of their names: Swift-Tuttle.

When it was first seen, Swift-Tuttle could only be viewed with a telescope. But in the nights that followed, it brightened rapidly. By the end of July 1862, the comet became dimly visible to the naked eye, and during August it began to increase its motion across the sky, passing 7 degrees from Polaris (the North Star) around Aug. 15 and then continuing south across the sky. (Reminder: Your fist held at arm's length measures about 10 degrees.)

During the last week of August, Comet Swift-Tuttle evolved into a strikingly beautiful object, becoming nearly as bright as Polaris and sporting an imposing tail that was about 30 degrees long. And through telescopes, observers saw luminous jets and fountains near its nucleus. During the following weeks, Swift-Tuttle rapidly faded, and by the beginning of October, its southward movement precluded further observations from the United States.

Several notable astronomers tried to calculate an orbit for the comet using scores of positional measurements, and the general consensus was that it was traveling in a very elongated orbit with a period of roughly 120 years.

At about the same time, Giovanni Schiaparelli of Italy began investigating the orbit of the Perseids and found that the orbital elements of the comet and the meteors were practically identical. It therefore became clear that debris shed from Comet Swift-Tuttle was the source of St. Lawrence's fiery tears: the Perseid meteor shower!

Comet bits

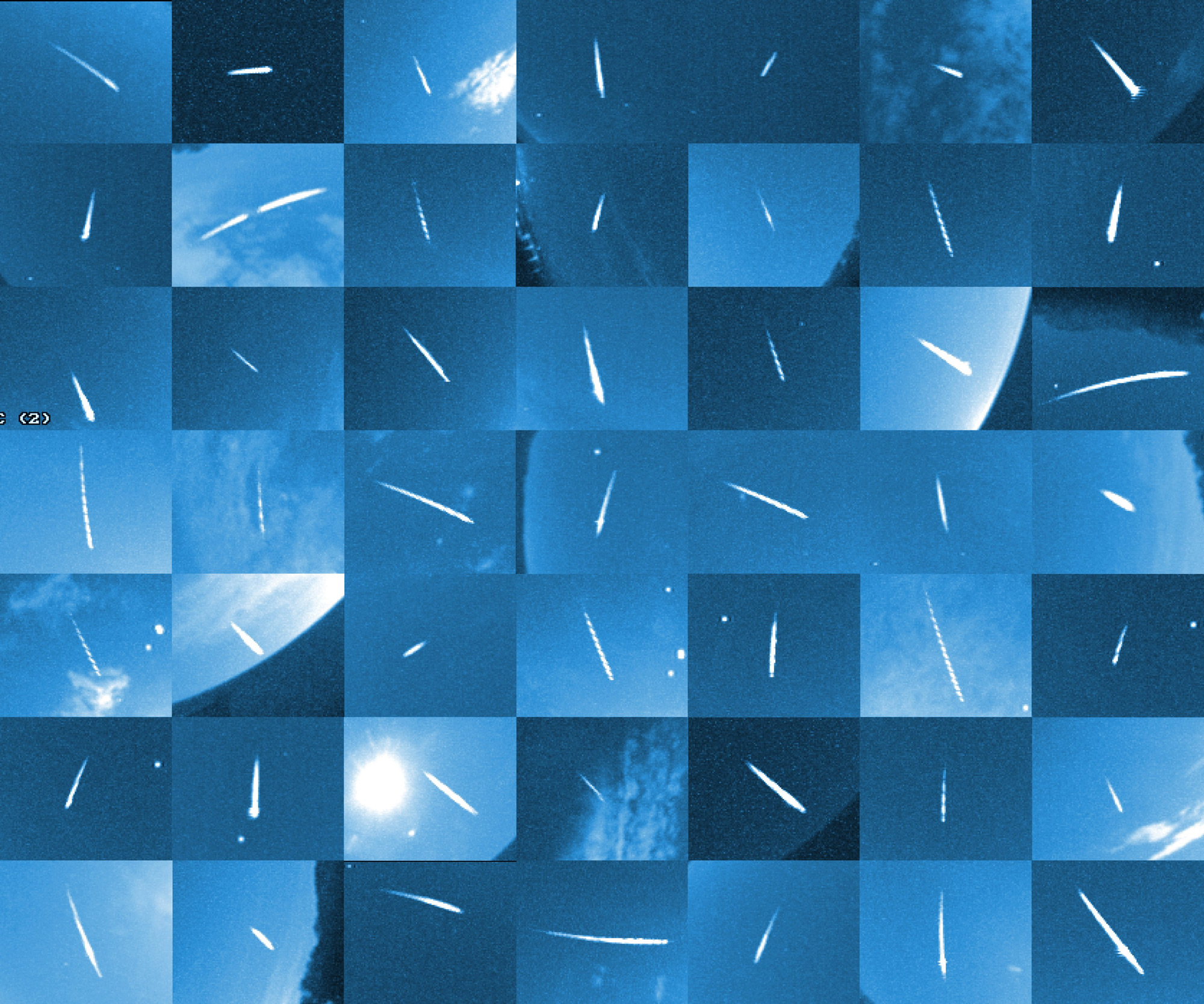

These tiny cometary fragments — countless bits of metal and stone — are called meteoroids while they cruise through space. They become meteors when they hit Earth's atmosphere. The streak of light we call a "shooting" or "falling" star is produced by the air surrounding a meteor, which is heated to incandescence by the object's plunge through the air.

Just as Comet Swift-Tuttle is the progenitor of the Perseids, the debris of other comets generates other meteor showers. (Halley's Comet, for example, is responsible for two annual showers — the April-May Eta Aquarids and the October Orionids.)

Comet Swift-Tuttle was due to return to the vicinity of the sun in 1981 or 1982, but failed to appear. About a decade earlier, however, astronomer Brian Marsden, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, had suggested that Swift-Tuttle might be the same comet that was reported in 1737 by a Jesuit missionary in Beijing named Ignatius Kegler.

The connection was possible if "nongravitational" forces — those luminous jets on the comet, caused by ice turning into gas because of the sun's heat — exploded out from the comet's surface and acted like rocket exhaust, slightly altering its orbit and slowing the comet down. Dr. Marsden assumed that, with a period of about 130 years — not the 120 years that was originally calculated — Comet Swift-Tuttle would return at the end of 1992. [Perseid Meteor Shower: Amazing Photos by Stargazers]

It did!

In the years surrounding the comet's return in 1992, the Perseids were far more intense than their usual 60 meteors per hour, instead producing brief bursts of up to several hundred per hour, many of which were dazzlingly bright and spectacular. This surge likely occurred because Swift-Tuttle's return to the inner solar system left more debris in Earth's path, researchers have said.

More good stuff on the way?

Even though Swift-Tuttle is now far back out in space, Perseid activity can still occasionally jolt upward. This year, it's hoped that a gravitational assist from Jupiter will push the Perseid stream nearly 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) closer to Earth's orbit and result in a much-better-than-average display.

There's also a chance of a brief burst of activity that might be caused by Earth's interaction with a thick cluster of debris shed by the comet back in 1079. From a clear, dark, nonlight-polluted location — and after the moon sets early on the morning of Aug. 12 — meteor rates in excess of 150 per hour this year seem possible.

And a well-known Finnish meteor expert suggests that the Perseids may provide an even greater show in years to come. Esko Lyytinen has calculated that the shower could produce 1,000 or more meteors per hour in 2028, as Earth passes within 37,000 miles (59,500 km) of a stream of debris that Swift-Tuttle released into space back in 1479.

Another meteor researcher, Mikhail Maslov from Russia, also expects that a meteor storm will occur in 2028. But his calculations suggest a more modest one, of perhaps 250 to 300 meteors per hour. [Top 10 Perseid Meteor Shower Facts]

Swift-Tuttle's future?

Because Comet Swift-Tuttle passes very close to Earth's orbit, there have always been concerns that it could one day collide with Earth.

In 1992, Marsden looked into the next return of Swift-Tuttle in 2126, warning that, if the actual date of the comet's closest approach to the sun was off by 15 days from his prediction of Aug. 14 (his 1992 prediction had been off by 17 days), a collision would be possible. Later, however, he was able to refine calculations of the comet's orbit accurately enough to account for the comet's position in space going back nearly 2,000 years; when he then looked ahead to 2126, he found that Swift-Tuttle would miss Earth by at least 15 million miles (24 million km).

Potential catastrophe averted.

However, looking even further ahead, Marsden found that, in August 3044, Swift-Tuttle will come within only about 1 million miles (1.6 million km) of Earth. By cosmic standards, that's a precariously close shave — especially considering that, at 16 miles (26 km) wide, the comet is a big one.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing photo of this year's Perseid meteor shower you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.