Rare Sight! Venus and Jupiter Will Appear to Nearly Touch on Saturday

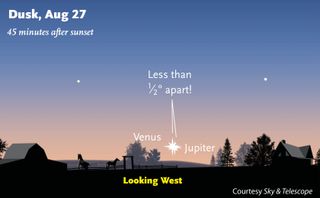

This Saturday night, make plans to get a clear view of the western horizon in order to see a celestial event that won't happen again until 2065.

Shortly after sunset, Venus and Jupiter will get so close to one another in the sky that, from some locations, they will appear to almost touch. At their closest approach, the two planets will be separated by less than one-eighth the width of the full moon.

If you plan to watch the event, make sure you have a clear view of the western horizon. The planetary pair will become visible about 30 minutes after sunset, positioned about 5 degrees above the horizon. (A clenched fist, held at arm's length, takes up about 10 degrees on the sky). [Venus-Jupiter Conjunction 2016: When, Where and How to See It]

Space.com columnist and skywatching expert Joe Rao reported that different sources vary in their calculation for when Venus and Jupiter will reach their very closest approach: either 6 p.m. EDT (2200 GMT) or 6:31 p.m. EDT (2231 GMT). But through the course of the night, the variation in their positions will be small.

The full moon takes up about 0.5 degrees on the sky. (However, most sky watchers misjudge the size of the moon; for more ways to determine celestial distances, check out this guide). Each degree can be divided up into 60 arc minutes (so the moon is about 30 arc minutes wide). At their closest approach, Venus and Jupiter will be separated by about 4 arc minutes (about 0.067 degrees). Venus (the brighter of the two objects) will appear just above Jupiter.

To viewers on the East Coast of North America, the separation after sunset will grow to about 5 arc minutes by sunset; that distance will grow to about 11 arc minutes for those on the West Coast of the U.S.

Viewers in Europe will see the two planets before closest approach, when they will be separated by between 6 and 12 arc minutes. Viewers in Japan and Asia will see the approach on the evening of Sept. 28, when the planets will be separated by about one half of a degree — still eye-catching, but not quite so rare.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Whenever two celestial objects are lined up along a vertical or horizontal line in the sky, it's called a conjunction. (To be more accurate, a conjunction happens when two objects have the same right ascension or same ecliptic longitude.) About eight to 10 times per decade, Venus and Jupiter enter a conjunction in the night sky, but Saturday's conjunction is something special. The two planets won't get this close again until 2065.

In addition, this event can be considered an "appulse," which refers to an instance when the separation between two celestial bodies is at an absolute minimum, Rao said.

This planetary close encounter is an illusion, of course; the orbital paths of these two planets are separated by about 416 million miles (about 670 million kilometers).

Don't forget to find a good viewing spot on Saturday night for this rare viewing event.

Editor's note: If you catch a photo of Venus and Jupiter's close encounter that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter