On 'Hidden Figures' Set, NASA's Early Years Take Center Stage

The little-known story of black women working as mathematicians at NASA in the 1960s is coming to the big screen early next year, and Space.com had the chance to visit the set of the new film.

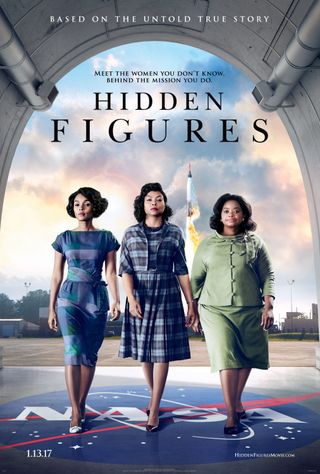

"Hidden Figures," set to premiere in January 2017, is based on the true story of Katherine Johnson and other black women whose calculations put Americans in space for the first time.

Space.com toured the Atlanta set of "Hidden Figures" this spring to see how the filmmakers are bringing 1961's NASA Langley Research Center to life. (At real-world Langley, a building was recently dedicated to the 98-year-old Johnson.) [Gallery: 'Hidden Figures' Movie Probes Little-Known Heroes of 1960s NASA]

This is "a movie that is very much on the surface about the early years of NASA and getting a man into space," said Jim Parsons, who plays a fictional NASA engineer named Paul Stafford in the film. "And it highlights three people who, because they were women and because they were African American, didn't get the credit they deserved for their input or contribution to this. So really, what we're doing here is a civil-rights-slash-feminist movie — and that's what's so wonderful about being here, and so exciting to be a part of."

Johnson's initial role at NASA (and NACA, or National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NASA's predecessor) was as a "computer" — a person who computes, as the electronic variety wasn't yet commonplace. Langley's first human computers were divided into an east wing and a west wing of women, separated by race, who worked to calculate trajectories for America's first suborbital and orbital launches.

The narrative is based on the book "Hidden Figures," by Margot Shetterly, which will be released Sept. 9. In fact, the film's producers chose it based on just a 55-page book proposal. For a focal point, the movie's creators chose John Glenn's flight into orbital space, which Langley mathematicians and engineers were intimately involved with planning and executing. It was a story with inherent drama, and the script even had technical consultants crying at the drama of the ending, Donna Gigliotti, the film's producer, told reporters.

As Space.com toured the set's mission control and met with actors and the show's creative team, their excitement for the subject matter was clear. As the film's director, Ted Melfi, put it, "The hardest thing about making a movie is trying to get everyone to make the same movie — and everyone's making the same movie."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Early NASA

To place the movie firmly in history and to be true to the technical detail of what human computers were doing at the time, the movie's creators consulted with NASA historians, experts at IBM and even an on-set mathematician. Plus, they drew from extensive notes and interviews that Shetterly had gathered during her research and writing process.

"When you do a period piece, the one thing that you are doing in terms of production design and costume is, you have to strive for authenticity," Gigliotti said. "It's as close as it can possibly be."

For "Hidden Figures," that authenticity came in the props — they rented some original consoles from the time for their mission control set, and built replicas for the rest — and in historical details from the time.

The creators worked with NASA's chief historian, Bill Barry, to comb through the script and make sure the details were true to NASA in 1961. Usually, NASA has to review a movie to allow it to use the agency's "meatball" logo, but this process was more in-depth.

"We think this is a project worth some time and energy on our part to make sure that the story gets told right," Barry said. "It's a great story in lots of respects, because it brings out the culture of the time."

Most people know the story of the space race, he said, but "the thing that I think gets missed a lot, from the perspective of where the field is going these days, is the stories about the real people," Barry added. For instance, "What was it like for somebody who was sitting there, cranking away at calculations and stuff?" he said. "And if they're a black woman living in Tidewater, Virginia, what was that like? How did that work?"

A lot of the cultural cues featured in the movie came from Shetterly's research and interviews with computers, as well as from her own memories — she is the daughter of a Langley scientist, and grew up surrounded by the lab's culture. The movie's screenwriter, Allison Schroeder, was immersed in NASA culture as well; her grandmother was a white computer at Langley, and her father was an engineer who worked on the Mercury capsule — the type of craft that John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth, rode into orbit in 1962.

"I think that the audience is going to be very surprised in 2016 when they look at this and see that, essentially, we sent John Glenn into orbital space in a tuna fish can," Gigliotti said. "It is true; that is what that thing looks like, and it has been recreated exactly and precisely. It is unbelievable how small that capsule is." [Infographic: 1st American in Orbit: How NASA & John Glenn Made History]

Doing the math

Calculating trajectories for a rocket or missile gets complicated quickly when you need to be precise, incorporating the atmosphere's friction, heating on the vehicle and many more variables while predicting where the capsule will land. And if you change the mass or surface area of the capsule or rocket, you'll have to calculate it all over again. That's why it took two whole wings of computers, all working to do the calculations needed, to propel the space program forward.

"One of the things we're interested in doing is actually explaining the kind of math that she [Johnson] had to create," Gigliotti said. "We're going to do it by explaining it with a tennis ball … A tennis ball, you throw it up in the air, and it comes down, and you know what the math is. What she had to do was, the tennis ball was thrown up in the air, and it has to circle the Earth three times, and then she's got to figure out where it comes down."

The movie's math consultant, Rudy Horne, a professor at Morehouse College in Georgia, verified the calculations and even trained the movie's cast to write equations while on camera. Plus, he made sure the background math scribbles as written were at least relevant to the scene. He also hoped to convey the excitement and the feeling of excelling at mathematics. "When you've banged your head against the wall of a problem for hours or days or weeks or months, then you finally get a notion of or know how to solve said problem," Horne said. "Sometimes, you wander around for a while, lost, and then you figure out what you need to do."

"That sense of accomplishment is sometimes hard to describe to people who aren't doing that," he added.

Three-part harmony

Taraji Henson, who plays Johnson in the film, found that the math focus made it hard to play her character. "Thinking about doing the calculations on the board; I broke out in hives last night," she said. (The set visit was during the first few days of filming.) "It scares me, because I want to do right by Ms. Katherine Johnson, who's still alive, and her family, and I want to do right by her legacy," Henson said.

When Schroeder talked with Johnson herself, Johnson insisted that they shouldn't focus only on her. Instead, she said, they should highlight the friendship between Johnson and two other women who worked at Langley with her: Dorothy Vaughan, head of the west computers and an early (electronic) computer programmer; and engineer Mary Jackson.

"I'd call us a three-part harmony," Henson said, referring to Johnson, Vaughan (played by Octavia Spencer) and Jackson (played by Janelle Monáe). "Dorothy's the bass. You have Mary; she's the spicy alto. And then Katherine is the soprano, the songbird," Henson said.

"Katherine Johnson said it was very important to her that we didn't just focus on her… that we needed to focus on the friendship between these three women, that they respected each other and didn't stab each other in the back," Schroeder said. "They lifted each other up."

The film's climax comes when Glenn becomes the first American to orbit the Earth — even though the historic trajectory was calculated by electronic computers, he insisted that Johnson check the computer's numbers personally beforehand, the show's producers said.

"At the most critical moment of our film, Katherine bears down with all the pressure in the world on a pencil and works it out," said Kevin Costner, who plays a fictionalized blend of the three Langley heads during Johnson's time at the research center. "She rose to the challenge. And that can put the hair on the back of your neck straight up."

"Math could do that?"

Pharrell Williams came on board to produce and write the soundtrack for the movie as soon as he heard about it, his producing partner Mimi Valdés said. Immediately, he offered up '60s-style music he'd been working on to add to the era's vibe.

"With this movie, he hopes that people will see this and be like, 'Oh gosh; math was able to do that?'" she said. "If a whole bunch of people start wanting to major in math, that would make him incredibly happy."

The movie's cast and creative team offered a variety of reasons for feeling so passionate about the film — for example, letting people know about a lesser-known set of NASA heroes, and showing the changing climate of the time for women and African Americans. But Williams' goal of inspiration came up again and again.

"It just blows my mind that little girls don't know that they can do this, and that's why it was madly important for me to do it," Henson said.

Horne — and Johnson herself — agree. "I think Katherine Johnson said it best: 'If you get even one little girl interested in math and science, then I think the movie accomplishes its feat,'" Horne said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.