Milky Way's 'Blowout Bash' May Explain Galaxy's Missing Mass

At the center of the Milky Way, there is a dormant supermassive black hole — but new research shows that the galactic core has not always been in a quiet slumber.

The center of the Milky Way was once incredibly active, with a superenergetic quasar feeding the galaxy's central black hole. However, 6 million years ago, the Milky Way's black hole marked its transition to hibernation with the explosion of the quasar, and shock waves from that explosion can still be seen today, according to scientists with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

CfA researchers were searching for some elusive matter that is thought to be missing from the Milky Way when they discovered evidence of these shock waves. [Dark Matter Missing From Milky Way Galaxy (Video)]

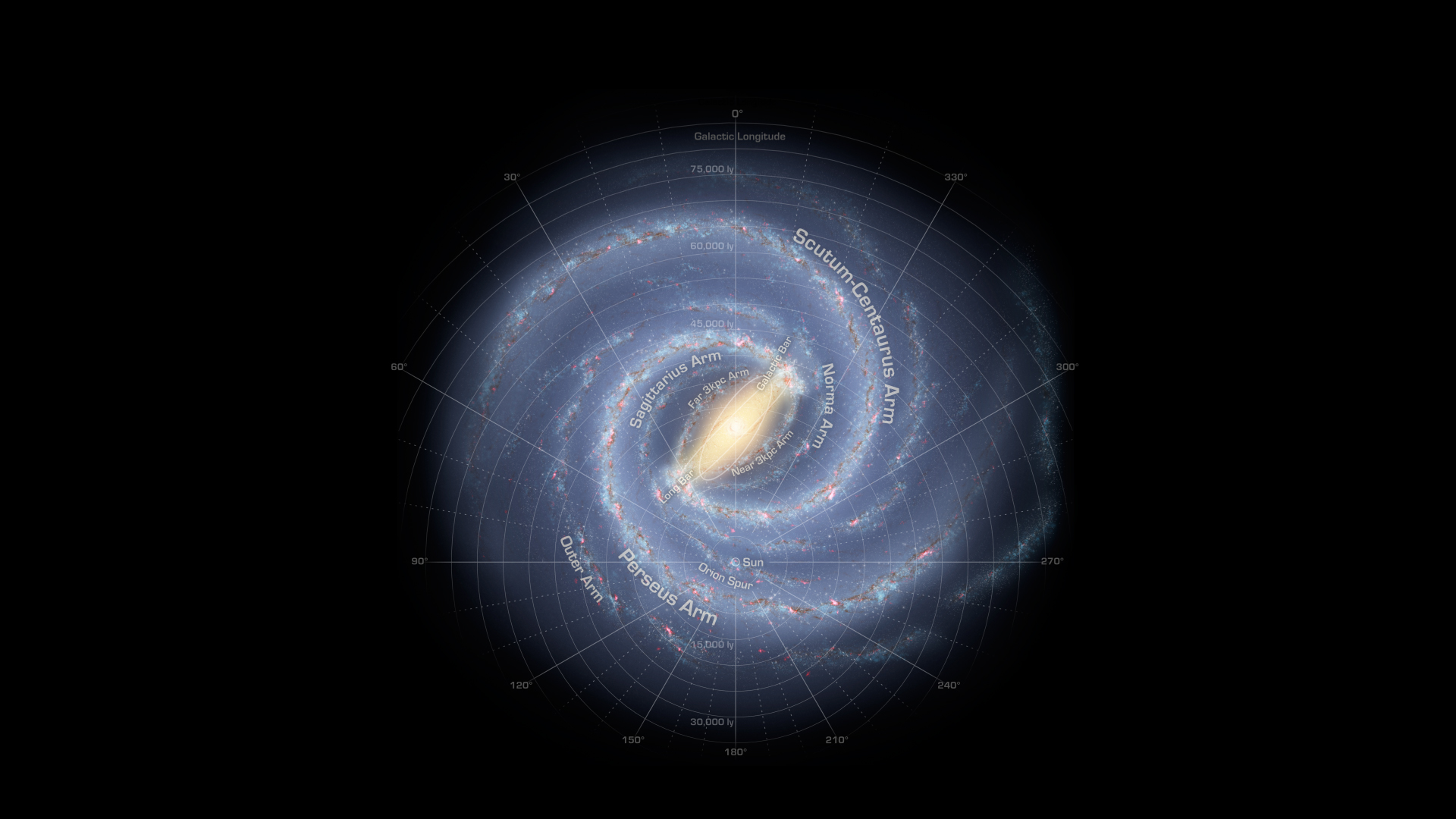

The Milky Way galaxy is estimated to be 1 trillion to 2 trillion times more massive than the sun, according to CfA researchers. Most of that mass (about five-sixths) is dark matter, while the remaining mass consists of normal matter — gas, dust and stars. Even still, when astronomers add up all of the visible matter in the Milky Way, something doesn't quite add up. Between 85 billion and 235 billion solar masses' worth of material appears to be missing, the researchers said in a statement.

"We played a cosmic game of hide-and-seek, and we asked ourselves, 'Where could the missing mass be hiding?'" Fabrizio Nicastro, lead author of the new study and a CfA research associate, said in the statement. "We analyzed archival X-ray observations from the [European Space Agency's] XMM-Newton spacecraft and found that the missing mass is in the form of a million-degree gaseous fog permeating our galaxy. That fog absorbs X-rays from more distant background sources."

Using measurements of X-ray absorption and computer models, the researchers were able to calculate how much normal matter was there and how it was distributed. However, they discovered their observations couldn't be explained by a smooth, uniform distribution of gas.

Instead, the researchers found that the gas was blown outward by the exploding quasar at the center of the Milky Way. Their findings suggest that this explosion occurred about 6 million years ago and that the shock waves created by the event created a gasless "bubble." Without gas, dust and stars to gorge on, the galactic core became inactive.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It would have required a lot of energy to create the "bubble," which the researchers said likely came from gas feeding the black hole. During this feeding frenzy, some infalling gas was swallowed by the black hole, while other gas was pumped out at speeds of 2 million mph (3.2 million km/h), the researchers said.

The material that flowed toward the black hole then would have accumulated to create new stars. Researchers found evidence of this in the presence of 6-million-year-old stars near the galactic center that are made of the same material, according to the new study, published Aug. 29 in The Astrophysical Journal.

"The different lines of evidence all tie together very well," Martin Elvis, co-author of the study and a researcher at the CfA, said in the statement. "This active phase lasted for 4 [million] to 8 million years, which is reasonable for a quasar."

The new study also shows that this million-degree gas weighs up to 130 billion solar masses, which could help to explain where all the galaxy's missing mass is — it's too hot to be seen, the researchers said.

Although this discovery does not completely solve the mystery of the Milky Way's elusive mass, it does give researchers a better understanding of the galaxy's composition and evolution.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.