Hubble Telescope Snaps Best-Ever Views of a Comet's Disintegration

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Building-size chunks of rock were photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope in January as they broke free from a disintegrating comet zooming around the sun. The relatively rare images are providing insight into how these icy space rocks die.

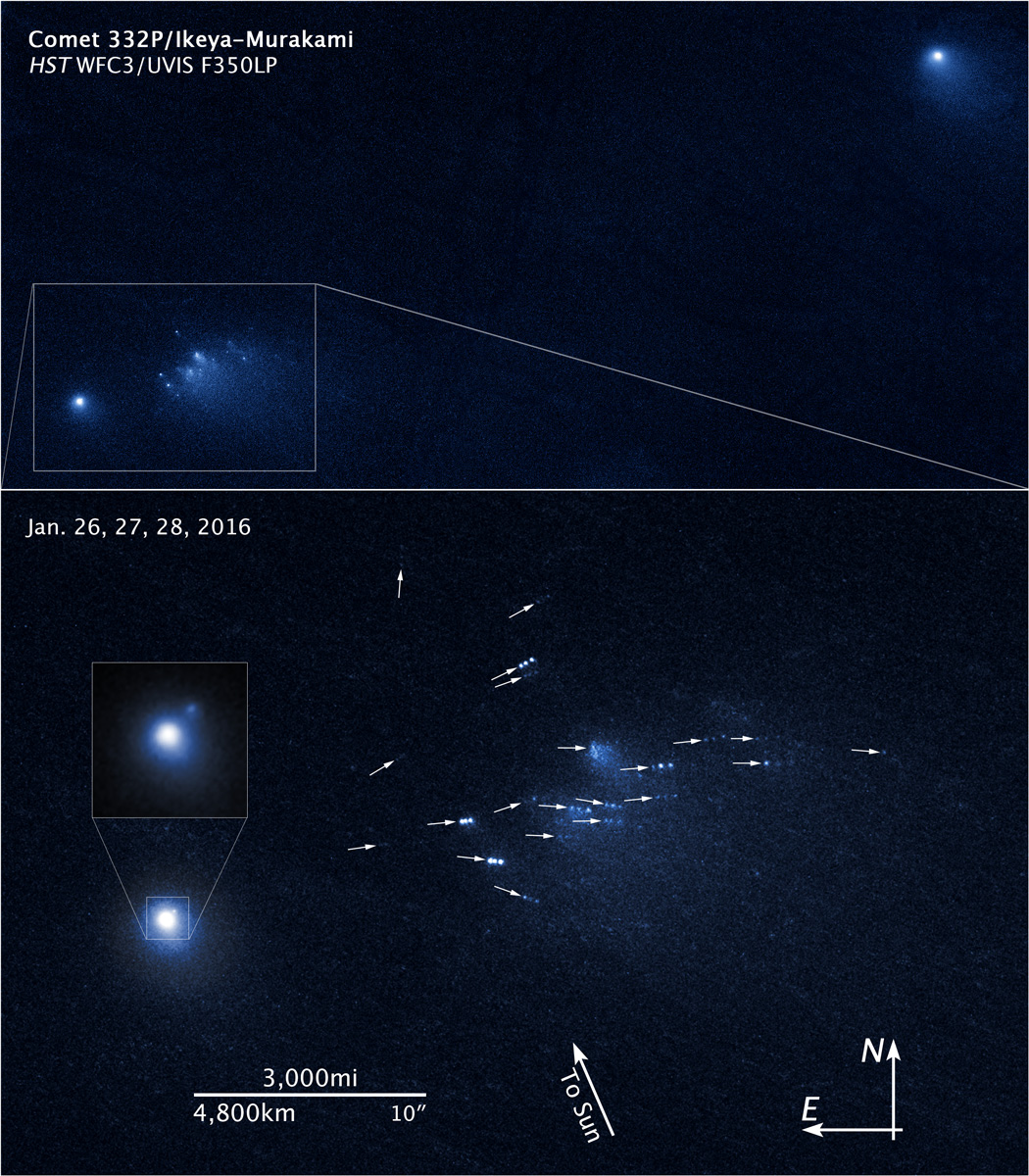

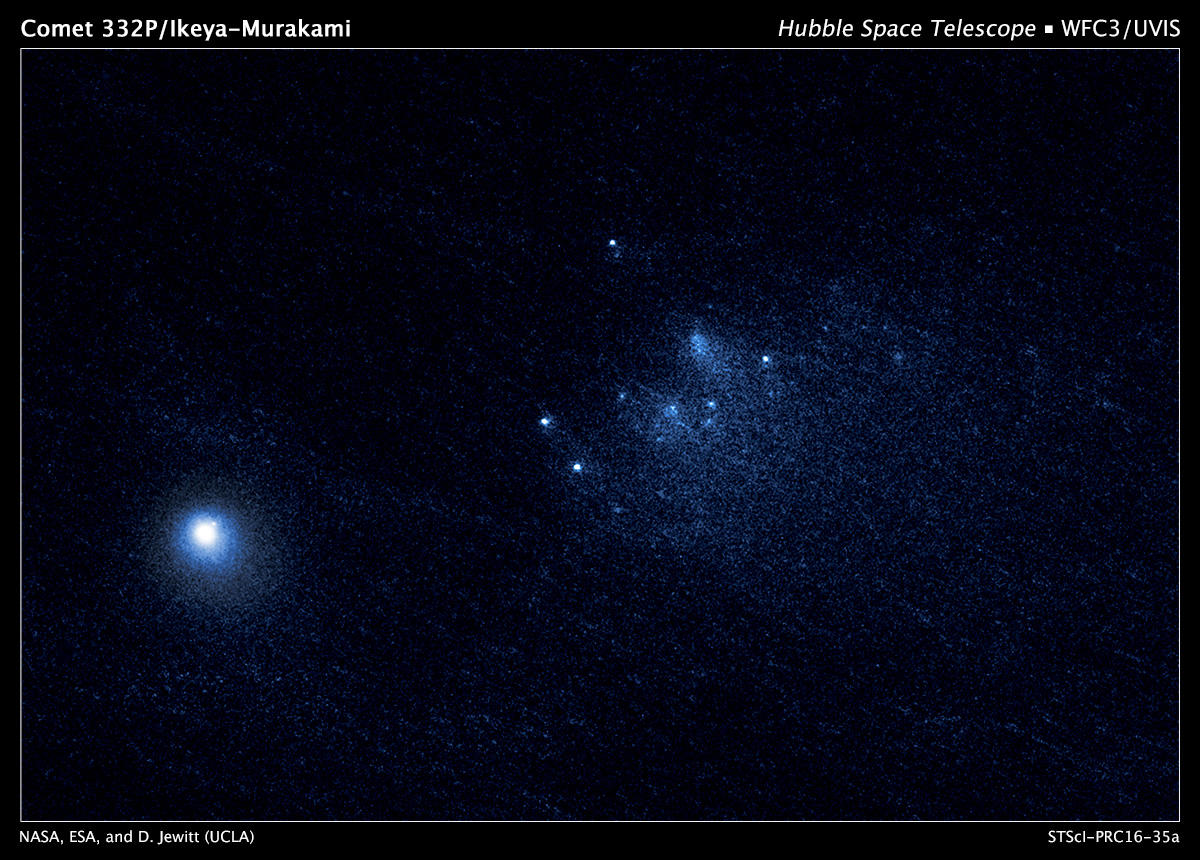

The new images show a large, bright speck of light — the solid core of Comet 332P (short for 332P/Ikeya-Murakami) — trailed by a parade of smaller bluish-white dots. Over the course of three days, those small dots can be seen falling farther behind the comet's main body.

Comet 332P is currently about the length of five football fields, but observations going back to 2010 show that its size has been deteriorating for some time. The comet and its debris trail are visible because they are made partly of ices that reflect sunlight. As comets approach the sun and temperatures start to rise, those frozen materials can vaporize, and the comet itself essentially becomes unglued. Currently, Comet 332P has a debris trail stretching about 3,000 miles (4,800 km) behind it, scientists said. [5 Amazing Facts about the Comet-Chasing Rosetta Spacecraft]

The new images of 332P are fascinating for scientists because there aren't many clear, direct observations of this type of cometary death; the photos make up "one of the sharpest, most detailed observations of a comet breaking apart," according to a statement from the Space Telescope Science institute (STScI) in Baltimore, which manages Hubble's science operations.

The images of the comet breaking apart were taken when the space rock was just outside the orbit of Mars, about 150 million miles (240 million km) from the sun, and only 67 million miles (108 million km) from Earth, researchers said.

Comet 332P is estimated to be about 4.5 billion years old, or about the age of Earth and the other bodies in the solar system. Comets originate in the Kuiper Belt, the sphere of rocky, icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune. At some point, gravitational disturbances pushed Comet 322P much closer to the sun, where the additional heat began to write its destruction. (The comet currently circles the sun once every six years.)

"We know that comets sometimes disintegrate, but we don't know much about why or how they come apart," David Jewitt, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California at Los Angeles, said in the statement. "The trouble is that it happens quickly and without warning, and so we don't have much chance to get useful data. With Hubble's fantastic resolution, not only do we see really tiny, faint bits of the comet, but we can watch them change from day to day. And that has allowed us to make the best measurements ever obtained on such an object."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jewitt is lead author on a paper analyzing the Hubble observations that appeared today (Sept. 15) in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. He and his colleagues applied to have Hubble turn its eye on the comet after other observations showed that it might be breaking apart.

In the new images, the larger bright spot of Comet 332P's nucleus (the rocky core of a comet) is estimated to be about 1,600 feet long (490 meters), with a debris trail. But observations in 2015 by the Pan-STARRS (Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System) telescope in Hawaii showed that there might be another chunk of rock very close to the comet's nucleus and almost the same size, suggesting 332P may have split nearly in half at some point in the past.

With the new observations, scientists are observing this rocky destruction as it happens. The chunks of rock visible in the Hubble images range in size from about 65 to 200 feet wide (20 to 60 meters), and are moving away from each other at "a few miles per hour," according to the statement, or "about the walking speed of an adult."

Observations of comets like Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko show that when icy comet materials heat up and turn into vapor, they can spray out of cracks and crevices in the comet's surface, creating jets. In Comet 332P, the jets of material act like engines that get the comet spinning faster and faster. The uptick then loosens chunks of material that fall off the comet.

"In the past, astronomers thought that comets die when they are warmed by sunlight, causing their ices to simply vaporize away," Jewitt said in the statement. "Either nothing would be left over or there would be a dead hulk of material where an active comet used to be. But it's starting to look like fragmentation may be more important. In Comet 332P we may be seeing a comet fragmenting itself into oblivion."

Scientists have previously captured images of debris breaking free of a comet, but the new Hubble observations are notable because they followed the comet long enough to show the "evolution of the fragments over time," Harold Weaver, a research professor of physics and astronomy at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, and an author on the new paper, said in the statement.

Comet 332P may not be long for this world (at least on the scale of a typical comet lifetime). The authors of the new paper estimate that another 25 outbursts will break the comet's nucleus apart completely.

"If the comet has an episode every six years, the equivalent of one orbit around the sun, then it will be gone in 150 years," Jewitt said. "It's the blink of an eye, astronomically speaking. The trip to the inner solar system has doomed it."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter