LAS CRUCES, N.M. — 2020 may be the year a private space station gets off the ground.

Two companies — Bigelow Aerospace and Axiom Space — plan to launch habitat modules to orbit in 2020, with the aim of making some money off Earth. If all goes according to plan, such habitats will eventually form the backbone of commercial facilities that replace the International Space Station (ISS), which is currently funded through 2024.

Down the road, such private space stations could host a variety of inhabitants, from space tourists to scientists to astronauts from NASA and other space agencies, advocates say. These tenants would simply rent the facilities rather than pay all the operating costs, as NASA and its partners must do now with the ISS. [6 Private Deep Space Habitats Paving the Way to Mars]

"Hopefully, if we're successful in the private-sector community, NASA's going to save a boatload of money, on multiple locations [in orbit] — not just one — with more volume than they've ever had before," Bigelow founder and CEO Robert Bigelow said here Wednesday (Oct. 12) at the 2016 International Symposium for Personal and Commercial Spaceflight (ISPCS). "So, whether it's Axiom or us or other people, that is the future."

Bigelow: Expanding humanity's footprint

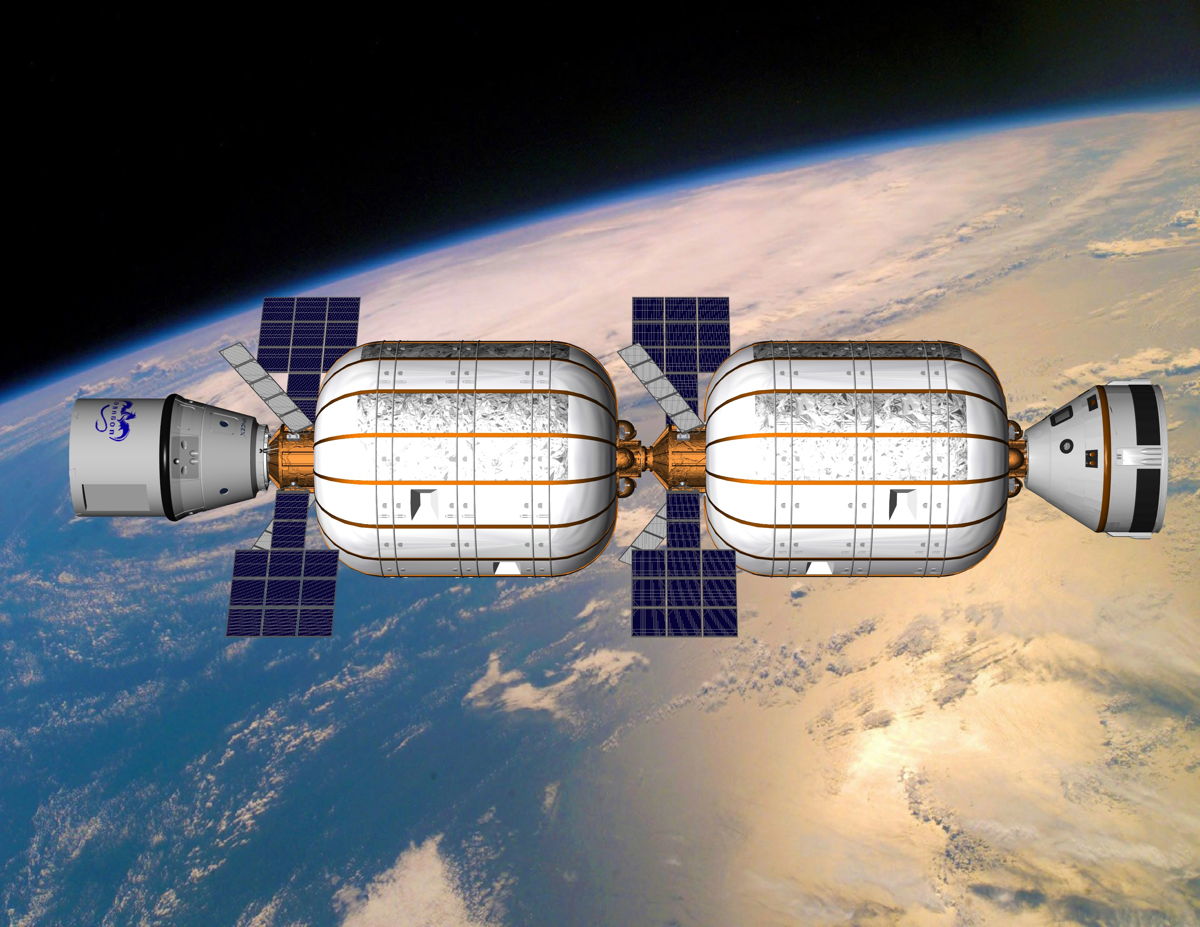

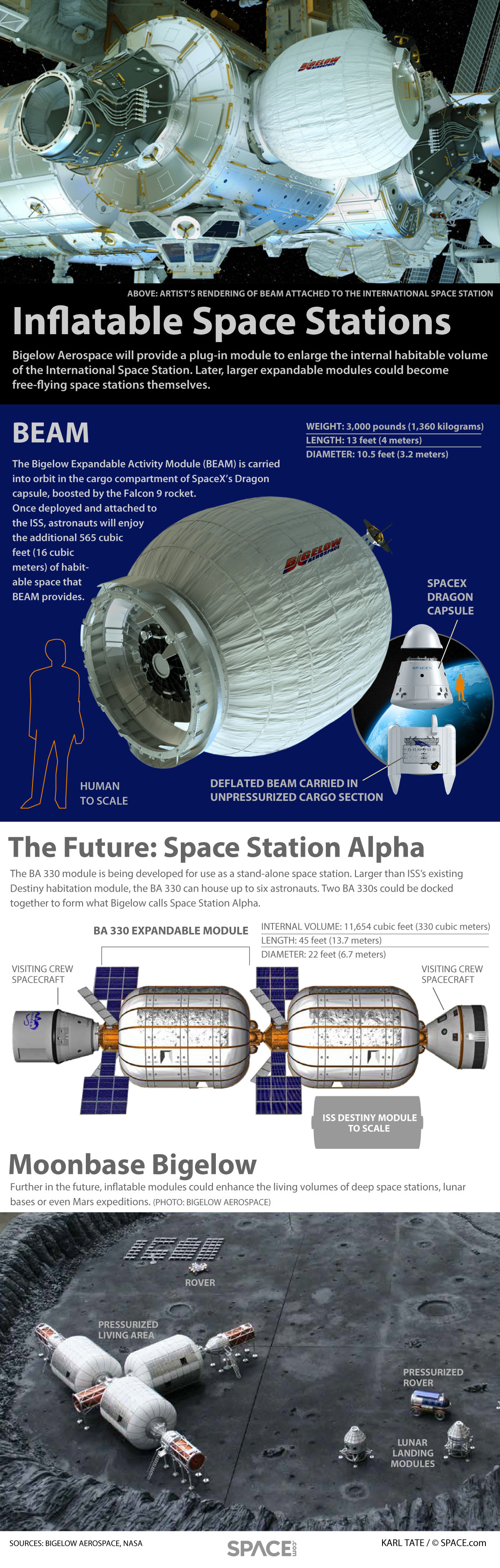

Las Vegas-based Bigelow Aerospace builds modules that launch in a compressed configuration and then inflate upon reaching their destination. These expandables feature much greater internal volume per unit launch mass than do traditional rigid modules, such as those that make up the ISS.

The company's expandable habitats also offer greater protection against micrometeoroid strikes and space radiation than do aluminum-walled structures, Bigelow said.

Bigelow Aerospace has already tested three experimental modules in orbit. It launched the free-flying Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 habitats in 2006 and 2007, respectively, and the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) was attached to the ISS this past April and inflated six weeks later.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nobody is aboard Genesis 1 or Genesis 2, which remain in orbit to this day. But ISS astronauts have ventured into the BEAM now and again to download sensor data, collect air samples and install equipment.

Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 are both 14 feet long by 8.3 feet wide (4.4 by 2.5 meters), with a post-expansion internal volume of 410 cubic feet (11.5 cubic m). BEAM is a bit bigger, featuring 565 cubic feet (16 cubic m) of usable volume. [The Bigelow Expandable Activity Module in Pictures]

But these are just prototypes. When it comes to fully operational space hardware, Bigelow has something much bigger in mind — a module called the B330, which will offer 11,650 cubic feet of internal volume. (That's 330 cubic meters, which explains the name.) For comparison, the internal pressurized volume of the entire 440-ton, $100 billion ISS is 32,333 cubic feet (916 cubic m), according to NASA.

The company aims to build two B330s over the next four years, Bigelow said.

"Our goal is to ship those out of Las Vegas in the year 2020, and launch them in 2020," he said.

Those launches will occur atop United Launch Alliance Atlas V rockets, as per an agreement between Bigelow and ULA that the two companies announced in April. The solar-powered B330 is so big that only the 552 variant of the Atlas V can loft it, Bigelow said.

The first B330 might link up with the ISS, Bigelow has said. But it doesn't have to do so.

"This constitutes a stand-alone space station," he said. "It needs no other support, no other modules, no other kinds of facilities."

That being said, Bigelow Aerospace also envisions connecting multiple B330s in orbit to create large space stations. Each individual B330 is capable of supporting six people, but orbiting modules probably won't be that crowded, Bigelow said. A station consisting of two B330s might typically host seven people — three Bigelow employees and four clients, he said Wednesday.

Axiom Space, too

Axiom Space plans to use a more traditional rigid-habitat module — one that's about 43 feet long by 16.5 feet wide (13 by 5 m) and weighs 50,000 lbs. (22,680 kilograms).

The company — which was co-founded by Mike Suffredini, a former NASA ISS manager — aims to launch that module in October 2020, perhaps aboard SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rocket.

"We're still looking at that," Axiom Space chief engineer Mike Baine said here at ISPCS 2016 on Wednesday, referring to the habitat's potential launch provider.

If all goes according to plan, Axiom's first module — which will be able to support seven people — will dock with the ISS and stay connected with the orbiting complex through the end of the latter's operational life, whether that comes in 2024 or sometime thereafter. Axiom Space envisions selling stints of varying lengths to a number of different customers, including researchers, space tourists and astronauts from nations that have traditionally lacked a way to get people to space, Baine said.

"There's a lot of interest by other governments looking to get into the space arena," he said during his ISPCS talk. Some of those governments will likely be "anchor customers" for Axiom, he added.

Then, when NASA and its partner agencies are getting set to ditch the ISS into Earth's atmosphere, the Axiom habitat will detach, meet up with another, recently launched Axiom module and form a self-sufficient space station in low-Earth orbit, Baine said.

Axiom Space hopes to keep building, launching and linking up modules, eventually creating an industrial "space city" of 100 or so people by the mid-2030s, Baine said.

Bigelow and Axiom may not be the only entities operating space stations in Earth orbit after the ISS ends its life. Since 2011, China has launched two space labs, to gain the expertise needed to build and operate a planned 60-ton station that the country aims to have up and running by 2022 or so.

Beyond Earth orbit?

Both Bigelow Aerospace and Axiom Space are focused on Earth orbit at the moment. But Robert Bigelow has long said that his company's expandable habitats offer great promise for the exploration of deep space.

"We have an architecture that we think is really practical to deploy these structures as a stand-alone base" on the lunar surface or the moons of Mars, he said Wednesday. "So, we're kind of excited about that."

Indeed, Bigelow Aerospace is one of six companies NASA recently selected to design prototype deep-space habitats that could help astronauts get to Mars. (Bigelow's future plans also include developing habitats much bigger than the B330.)

Axiom's module could "in principle" be adapted for use on the lunar surface, Baine said, though he didn't discuss that possibility in depth.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.