Massive 'Baby' Stars Are Born with Cosmic Fireworks

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

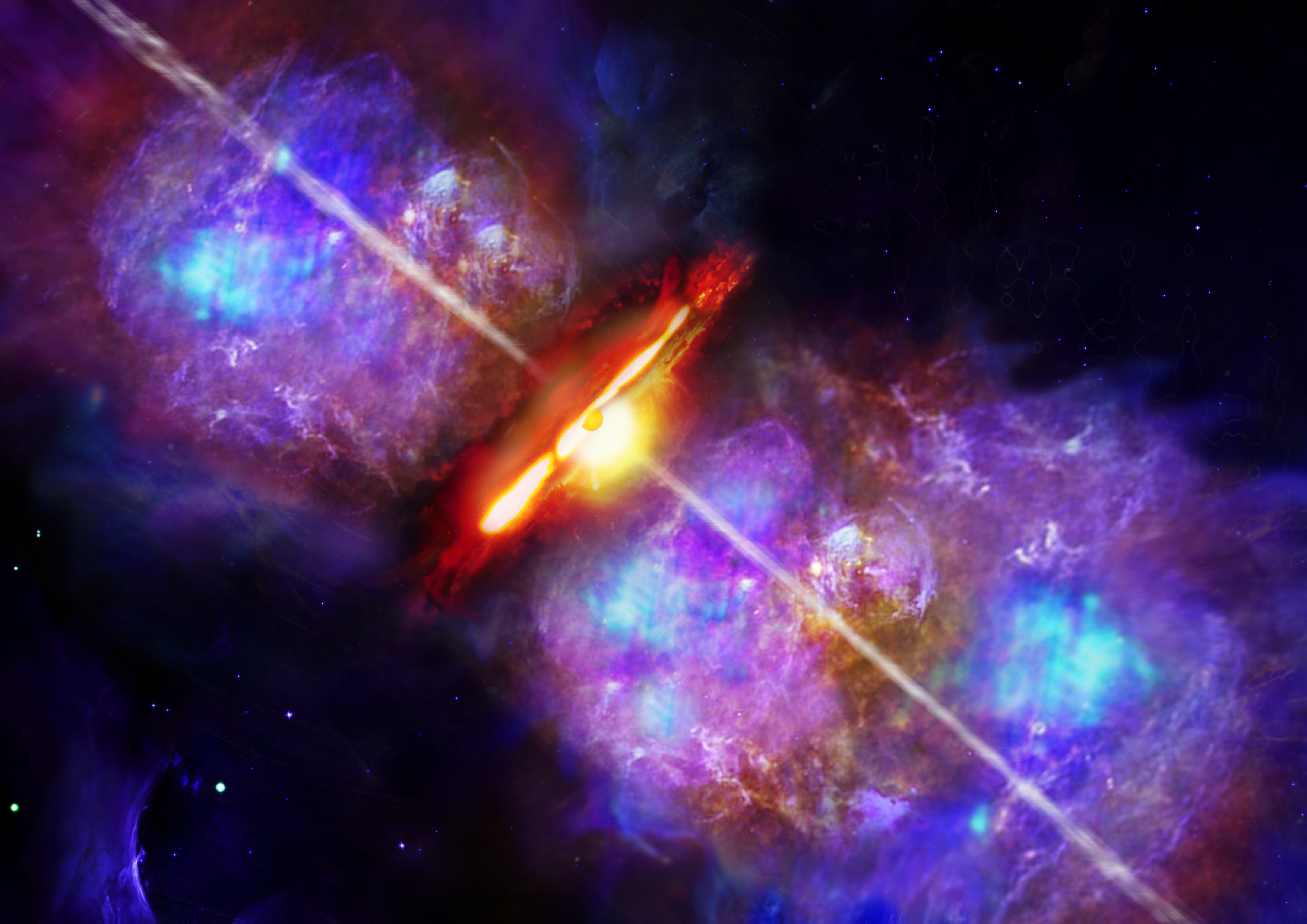

The universe celebrates the birth of massive stars with cosmic fireworks, just as it does with its smaller siblings, a new study shows.

Stars the size of the sun produce outbursts as they interact with the disk of material around them, but larger stars shine so brightly that scientists thought their disks would burn away quickly. For the first time, astronomers have spotted periodic explosions in the material surrounding a massive star as it swallows a planet-size clump of gas from its disk, suggesting that these giant stars form the same way as their smaller counterparts.

"These outbursts, which are several orders of magnitude larger than their lower-mass siblings, can release about as much energy as our sun delivers in over 100,000 years," Alessio Caratti o Garatti, an astronomer at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in Ireland, said in a statement. Caratti o Garatti led a team that made observations from multiple instruments to study a massive young star. [The Biggest Star Mysteries Ever]

"Surprisingly, the fireworks are observed not just at the end of the lives of massive stars, as supernovae, but also at their birth!" he said.

A time-lapse movie

Stars form as gravity draws gas and dust together in space. For stars like the sun, the material flattens into an accretion disk, falling into the center, where the star is born. But the higher radiation produced by the largest stars, which can weigh more than 100 times the mass of the sun, was thought to burn away the disk around it, keeping material from falling inward and requiring another path to their birth.

Using the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, the European Southern Observatory in Chile, the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain and the California-based SOFIA Observatory, which is mounted on an airplane, the astronomers spotted explosive outbursts in the disk surrounding a massive star about 6,000 light-years from the sun. As the star swallowed an enormous gob of gas about twice as massive as Jupiter, it released bursts of energy revealed as a bright flare-up around the star. According to the researchers, the fireworks suggest that the material survived the destructive radiation previously thought to obliterate it to fall onto the large stars, echoing the process followed by smaller stellar objects.

"How accretion disks can survive around these massive stars is still a mystery," Caratti o Garatti said in the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The disk that produces the fireworks makes star birth challenging to spot because the dense material lies between Earth and the star. Infrared telescopes such as Gemini can pierce through the cloud to spot what's happening at the center. Unlike their smaller siblings, the largest stars lie farther away from the sun, adding to the difficulty. And, compared to stars like the sun, the birth of massive stars is brief, lasting only about 100,000 years, according to Caratti o Garatti. In contrast, smaller stars like the sun can take hundreds of times longer to form.

"When we study the formation of higher-mass stars, it's like watching a time-lapse movie when compared to less-massive stars," Caratti o Garatti said. "Although the process for massive stars is fast and furious, it still takes tens of thousands of years."

Previous studies suggested that outbursts around other stars last only a few years. The team estimated that the burst they studied started about 16 months ago, and it is continuing to release energy weakly today, they said.

"While this research presents the strongest case yet for similar formation processes for low- and high-mass stars, there is still a lot to understand — especially whether planets can form in the same way around stars at both ends of the mass spectrum," team member Bringfried Stecklum, an astronomer at the Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg in Germany, said in the statement.

The research was published Nov. 14 in the journal Nature Physics.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd Facebook or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky