Potentially Habitable Planet's Shadow Spotted from Earth

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A potentially Earth-like planet circles a bright star 150 light-years away, casting a shadow tracked from space — and now from Earth, too.

The planet, called K2-3d, was originally seen crossing in front of its star by NASA's Kepler space telescope during that instrument's ongoing K2 mission. Researchers brought the Okayama Astrophysical Observatory's 188-centimeter (6 feet) telescope to bear on the speck to fine-tune their understanding of the exoplanet's orbit down to a precision of 18 seconds, according to new research.

Using this first-ever Earth-based measurement of the planet, the researchers predicted when the planet will cross its star in 2018, when the newly complete James Webb Space Telescope should be able to watch carefully and analyze the planet's atmosphere for potential signs of life or habitability. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

K2-3d is about 1.5 times the size of Earth and orbits a star half the size of the sun every 45 days. The exoplanet circles closer to its star than Earth does around the sun — one-fifth the Earth-sun distance — but because this is a cooler star, the planet should rest at an Earth-like temperature that could host liquid water, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan researchers said in a statement. That space around a given star is known as the habitable zone because it has the potential to support life similar to that found on Earth.

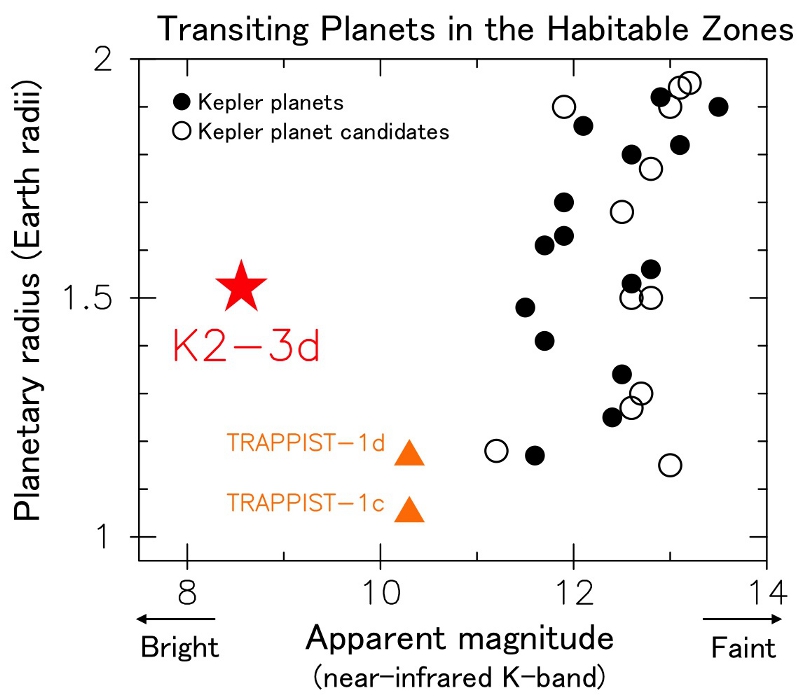

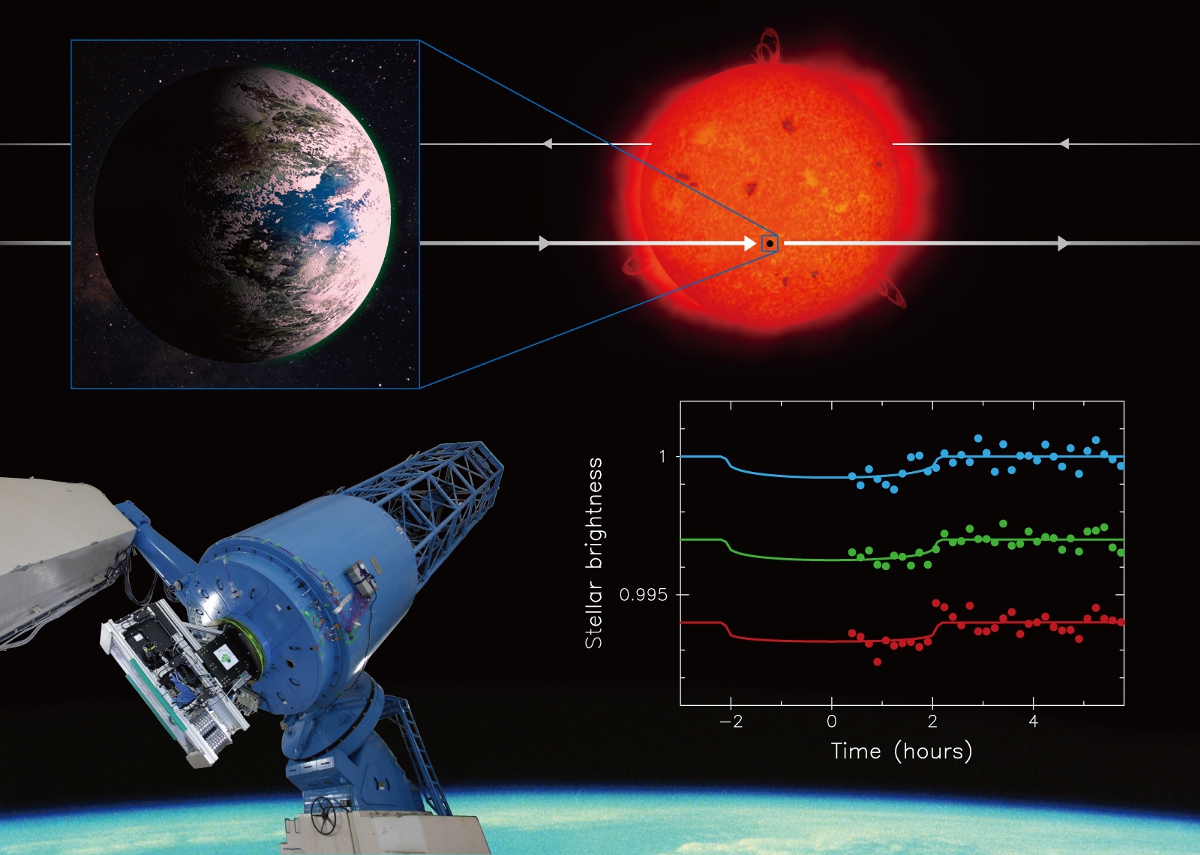

Kepler discovered the planet based on the star's slight dimming as the planet passed in front, from the telescope's perspective — a process of discovery called the transit method. Because Kepler's K2 mission examines patches of the sky for only around 80 days each, researchers could observe K2-3d crossing the star just twice. But the planet is closer to Earth and has a brighter host star than most of the other potentially habitable planets discovered by Kepler, researchers said in the statement, so K2-3d was worth a second glance. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope observed two more transits, further increasing what researchers knew about the planet's orbit.

Despite its closeness to Earth, K2-3d is small enough that the dip in brightness of its star is still extremely faint, only a 0.07 percent change. That's near the limit of what ground-based telescopes can detect, the researchers said, but Okayama's MuSCAT instrument could collect light from three different wavelengths and so could detect that flicker, thus clarifying the orbit to within just 18 seconds.

Each transit presents a chance to learn more about K2-3d, and this new work allows researchers to forecast when those transits will occur. Upcoming large-scale telescopes like the James Webb Telescope will be able to analyze the starlight shining through the planet's atmosphere during a transit. They will thus be able to detect molecules like oxygen that can indicate the potential existence of life.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new work was described Nov. 21 in The Astronomical Journal.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.