Gears Made of Metallic Glass Could Be Ideal for Space Missions

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A material known as metallic glass, created by liquefying and then rapidly cooling metal, might be an ideal material for making gears for spacefaring robots, according to new research.

The two new research papers focused on the use of bulk metallic glass (BMG) as a material for crafting gears for space-based missions. Metallic glass is called BMG when it is used to manufacture products larger than 0.04 inches (1 millimeter).

To make BMG, engineers first melt metal. Solid metals have a well-organized, crystalline atomic structure. But when the metal is melted, the atoms lose that structure and become randomly arranged, according to a statement from NASA. If the metal cools slowly, the atoms will go back to the crystalline arrangement. But if the liquid metal is cooled extremely rapidly — about 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 degrees Celsius) per second — then the disorganized atomic structure remains. [Video: NASA Tests Robotic Refueling Tech]

These rapidly cooled metals are also known as amorphous metals, and "by virtue of being cooled so rapidly, the material is technically a glass. It can flow easily and be blow-molded when heated, just like windowpane glass," NASA scientists explained in the statement.

Metallic glass was first developed at the California Institute of Technology in the 1960s, and "has been used to manufacture everything from cell phones to golf clubs," NASA said in the statement.

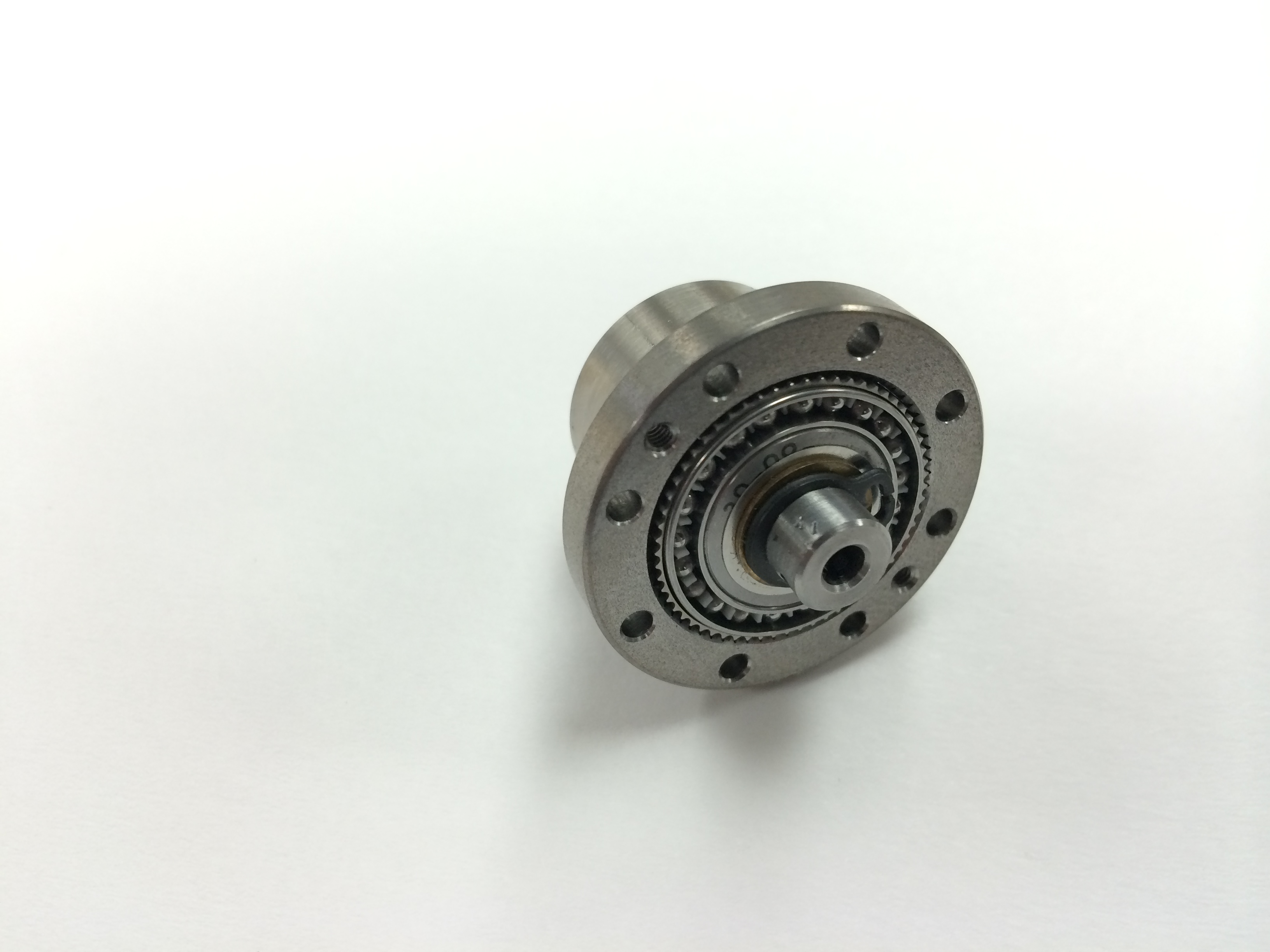

To find out if BMG might be a good material for making gears for spacecraft, Douglas Hofmann, a technologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the lead author on the two new research papers, made gears from BMG and tested them at very low temperatures. One of the new papers, published in the journal Advanced Engineering Materials, shows that the gears demonstrate "strong torque" and smooth operation without lubricant at temperatures reaching minus 328 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 200 degrees Celsius).

The gears' ability to function at very low temperatures is important for two reasons. First, some materials (including some metals) become brittle at cold temperatures, but that isn't the case with metallic glass.. That means there's less risk that a gear tooth will break during operations, according to the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The second benefit has to do with power consumption. "Being able to operate gears at the low temperature of icy moons, like [Jupiter's] Europa, is a potential game changer for scientists," said R. Peter Dillon, a technologist and program manager in JPL's Materials Development and Manufacturing Technology Group. "Power no longer needs to be siphoned away from the science instruments for heating gearbox lubricant, which preserves precious battery power."

Other benefits of BMG gears may result from low cost and ease of manufacturing. Parts made from BMG can be cast using injection-molding technology, according to the NASA statement, which means the material is liquefied and injected into a mold. This technique is also used to manufacture plastic parts.

The second paper by Hofmann and colleagues demonstrates that BMG gears might be more cost-effective than so-called strain wave gears, which are "ubiquitous in expensive robots," according to the statement. In particular, these gears include a flexible metal ring that is "tricky to mass-produce and ubiquitous in expensive robots," NASA officials said in the statement. BMG gears can be manufactured for less, according to the paper.

"Mass-producing strain wave gears using BMGs may have a major impact on the consumer robotics market," Hofmann said. "This is especially true for humanoid robots, where gears in the joints can be very expensive but are required to prevent shaking arms. The performance at low temperatures for JPL spacecraft and rovers seems to be a happy added benefit."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter