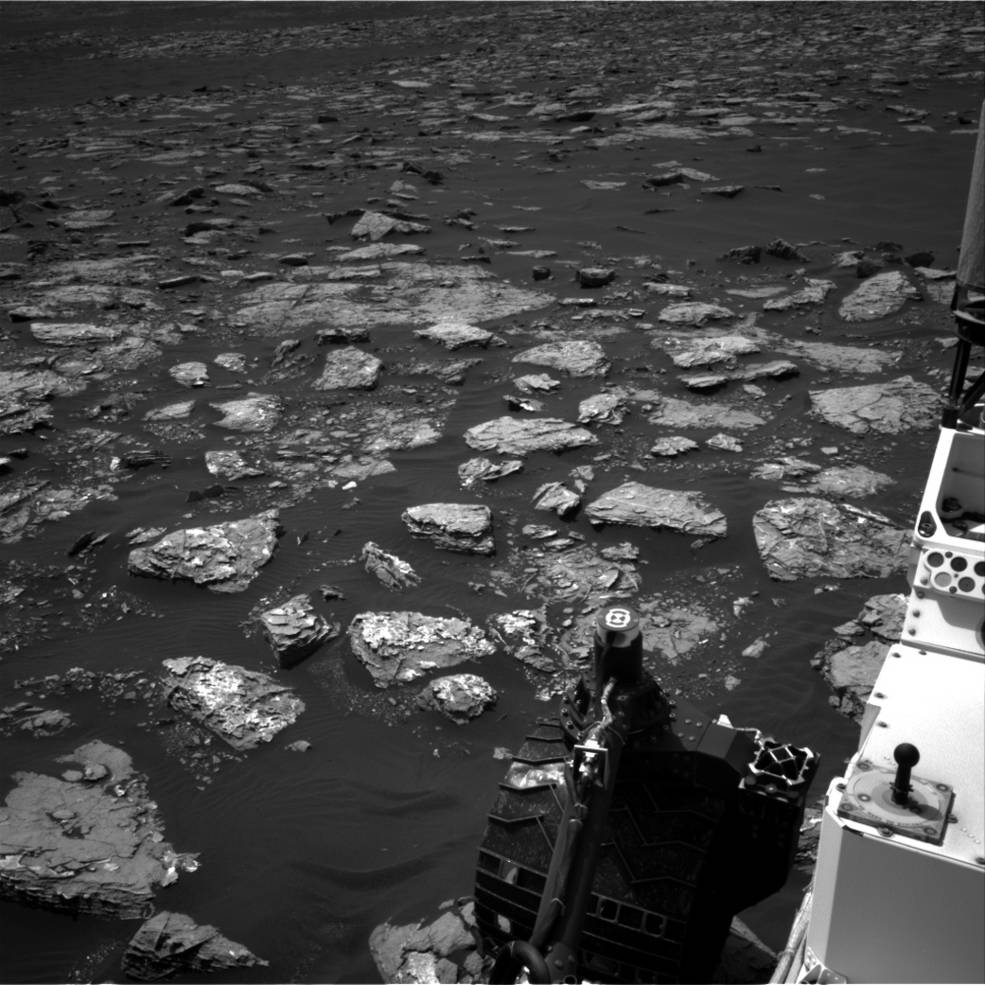

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover has stopped driving and using its 7-foot-long (2.1 meters) arm while mission controllers investigate a problem with the robot’s sample-collecting drill.

Curiosity was supposed to begin its seventh drilling operation of 2016 last week. But team members learned on Thursday (Dec. 1) that the car-size rover detected a problem with its "drill feed mechanism" — which pushes the drill outward from a turret at the end of Curiosity's arm — and failed to complete the command.

"We are in the process of defining a set of diagnostic tests to carefully assess the drill feed mechanism. We are using our test rover here on Earth to try out these tests before we run them on Mars," Curiosity deputy project manager Steven Lee, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement Monday (Dec. 5). [Amazing Mars Photos by NASA's Curiosity Rover (Latest Images)]

"To be cautious, until we run the tests on Curiosity, we want to restrict any dynamic changes that could affect the diagnosis," Lee added. "That means not moving the arm and not driving, which could shake it."

Curiosity is not in a precautionary "safe mode," however. The rover continues to study its surroundings on the lower slopes of the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) Mount Sharp using the cameras and spectrometer on its head-like "mast," as well as its weather-station gear, which is attached to the mast and Curiosity's body, NASA officials said.

Meanwhile, the rover team is trying to figure out what caused the drill issue.

"Two among the set of possible causes being assessed are that a brake on the drill feed mechanism did not disengage fully, or that an electronic encoder for the mechanism's motor did not function as expected," NASA officials wrote in the same statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It may be possible to work around either of these issues, Lee said.

Curiosity's drill bores into rock using both rotating and percussive (hammering) action. Last week's attempt would have been the first time the rover used just the rotary aspect, NASA officials said. (Short circuits in the percussive component have occurred several times over the past two years or so, temporarily sidelining Curiosity.)

"We still have percussion available, but we would like to be cautious and use it for targets where we really need it, and otherwise use rotary-only where that can give us a sample," said Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, also of JPL.

The $2.5 billion Curiosity mission touched down inside Mars' Gale Crater in August 2012, tasked with determining whether or not the area could ever have supported microbial life. The rover quickly found plenty of evidence in the affirmative, determining from drilled samples that Gale hosted a long-lasting lake-and-stream system in the ancient past.

Curiosity is now climbing up through the foothills of Mount Sharp, which lies in Gale's center. The six-wheeled robot is searching for clues about how, why and when Mars transitioned from a relatively warm and wet world long ago to the cold, dry planet it is today.

To date, Curiosity has driven 9.33 miles (15.01 km) on Mars, gained 541 feet (165 m) in elevation and drilled into 15 rocks, NASA officials said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.