Weird Clouds Linger on Saturn's Moon Titan

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

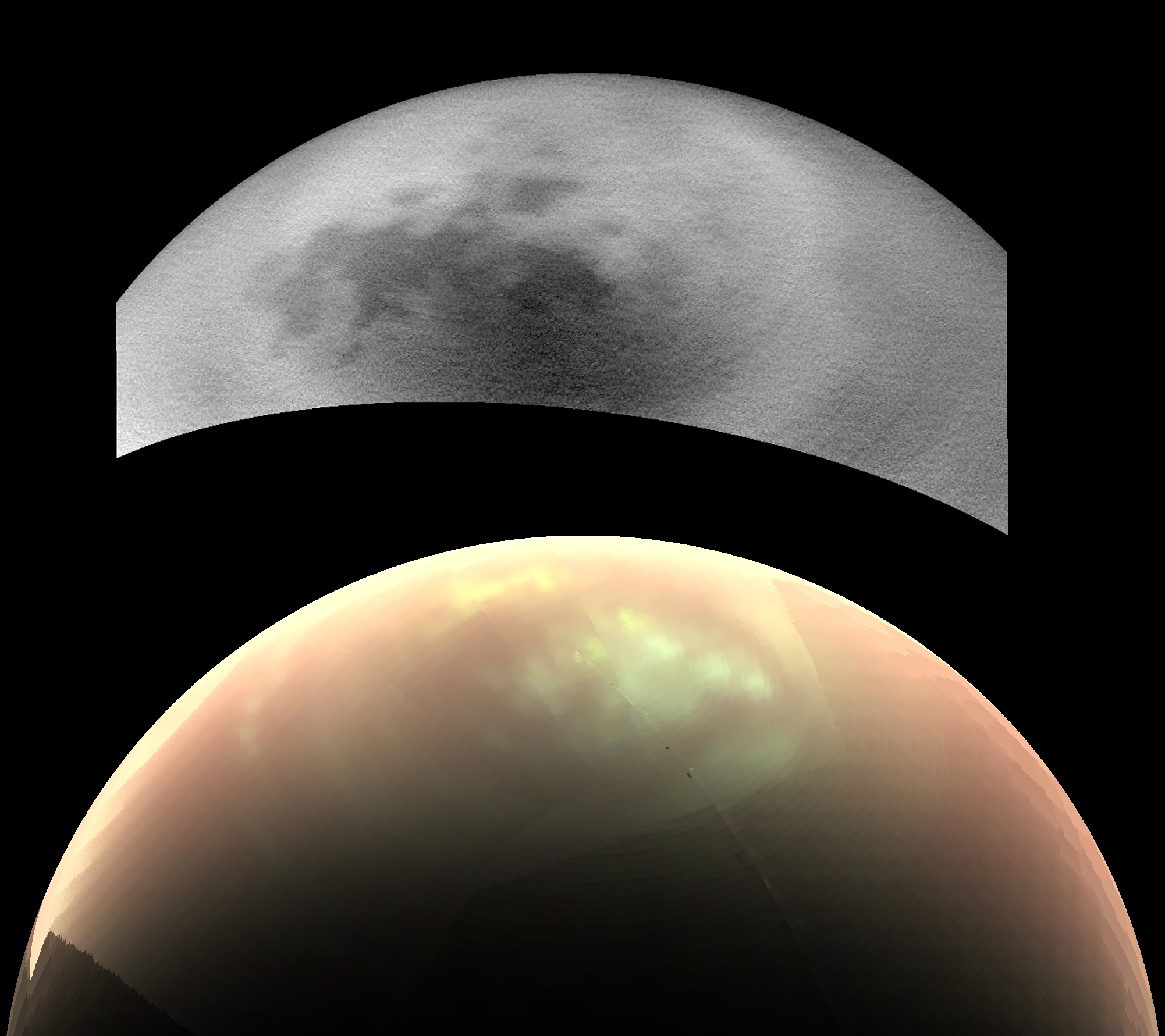

Mysterious, thin, wispy clouds hide under the hazy upper atmosphere of Saturn's largest moon, Titan.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft flew over Titan on June 7 and July 25 and captured strikingly different photos of the moon's high northern latitude using the probe's Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) and Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS). Only the VIMS (the bottom, color image) was able to peer through the moon's hazy atmosphere to capture an infrared view of the elusive clouds. The VIMS image shows widespread cloud cover during both flybys.

The different views captured by Cassini's two onboard imaging cameras raise the question of why clouds would be visible in some images but not others, according to a NASA image description. That's especially puzzling because the two images were taken fairly close together in time. [Gigantic Ice Cloud Spotted on Saturn Moon Titan (Photos)]

ISS consists of a wide-angle and a narrow-angle digital camera, which are sensitive to visible wavelengths of light and to some infrared and ultraviolet wavelengths. The monochrome image at the top was captured by ISS from a distance of about 398,000 miles (640,000 kilometers) and is almost cloud-free. However, the bottom image was captured from about 28,000 miles (45,000 km) by the VIMS at the longer, infrared wavelength, and bright clouds are visible in Titan's northern skies.

"Even though these views were taken at different wavelengths, researchers would expect at least a hint of the clouds to show up in the upper image," NASA officials said in a statement. "Thus, they have been trying to understand what's behind the difference."

Based on atmospheric models, scientists have predicted that clouds will become more common at high northern latitudes during summer on Titan. Since 2004, Cassini has documented alterations in weather patterns as seasons change on Titan. Images collected by Cassini will help track the onset of clouds in the north, where Titan's lakes and seas are located, NASA officials said.

"The answer to what could be causing the discrepancy [between the ISS and VIMS images] appears to lie with Titan's hazy atmosphere, which is much easier to see through at the longer infrared wavelengths that VIMS is sensitive to (up to 5 microns) than at the shorter, near-infrared wavelength used by ISS to image Titan's surface and lower atmosphere (0.94 microns)," NASA officials said in the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Differences in illumination geometry or changes in the clouds themselves were ruled out, as the images taken by ISS and CIMS were made over the same 24-hour period.

"High, thin cirrus clouds that are optically thicker than the atmospheric haze at longer wavelengths, but optically thinner than the haze at the shorter wavelength of the ISS observations, could be detected by VIMS and simultaneously lost in the haze to ISS — similar to trying to see a thin cloud layer on a hazy day on Earth," NASA officials said. "This phenomenon has not been seen again since July 2016, but Cassini has several more opportunities to observe Titan over the last months of the mission in 2017, and scientists will be watching to see if and how the weather changes."

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.