Cassini Says Farewell to Saturn's Delicious 'Ravioli' Moon Pan

The Cassini spacecraft has bid a photo farewell to Saturn's adorable, delicious-looking moon, Pan.

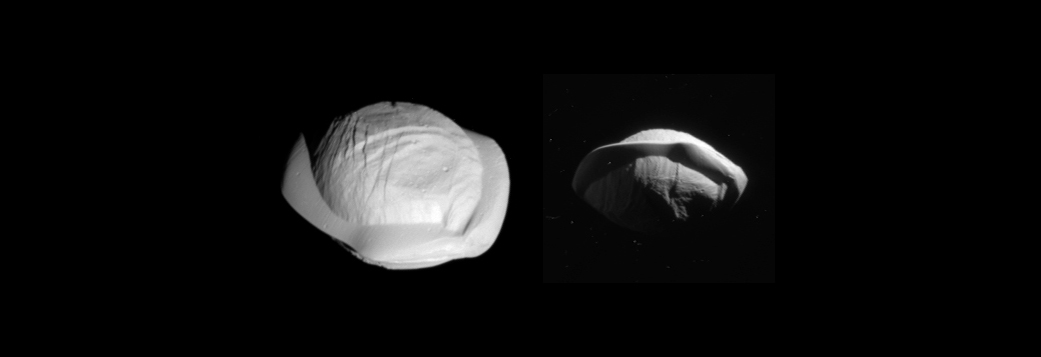

On March 7, the probe made observations of Pan that turned out to have eight times better resolution than any previous images ever taken of the small satellite. The Cassini images revealed that pan has a unique shape: a bulging midsection with a flat disk wrapped around it.

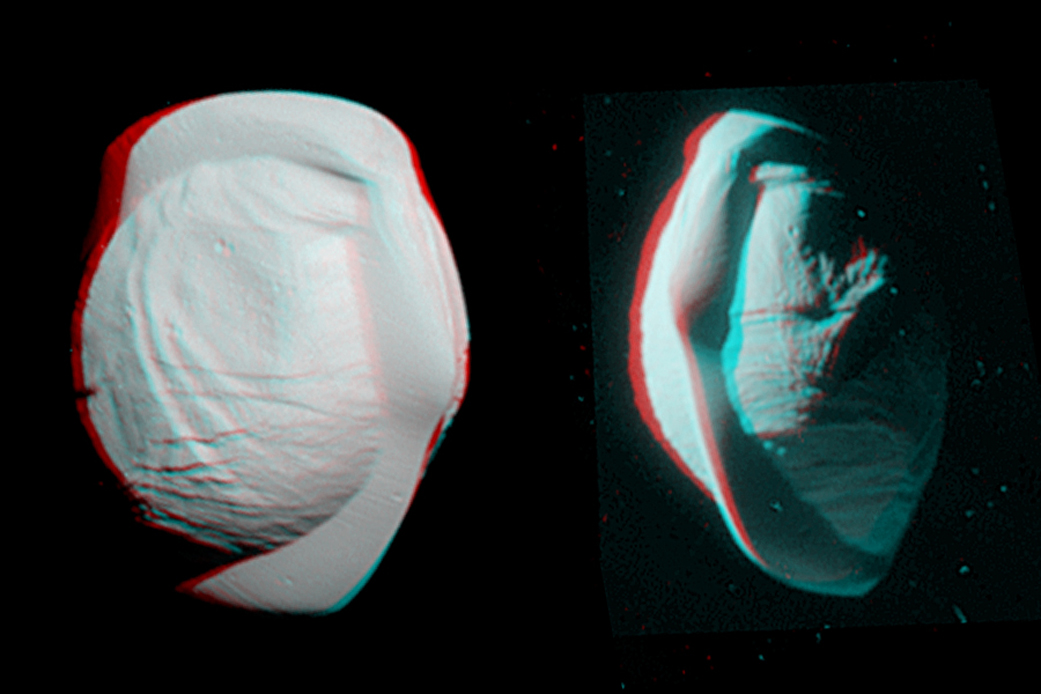

New images released by NASA shows Cassini's view of Pan as the spacecraft approached the moon, and then as the craft moved away. The image shows the moon's northern and southern hemispheres. In the first set of images, the view of Pan on the left was taken at a distance of about 15,300 miles (24,600 km); the image on the right was taken at a distance of about 23,200 miles (37,300 km). A second set of images offer stereo views of Pan that appear 3D with red-blue glasses. Those images were taken by Cassini from a distance of 16,000 miles or 25,000 kilometers (left view) and 21,000 miles or 34,000 kilometers (right view). [In Photos: Amazing Color Maps of Saturn's Moons]

Pan's shape has drawn comparisons to a piece of pasta or dough, stuffed with who-knows-what kind of delicious filling. Thin, straight ridges can be seen across the moon's central bulge, looking almost as though someone dragged a very large fork across the moon's surface.

The disk or ridge around Pan's equator likely formed long after the central bulge, once the tiny moon had carved out a clearing in Saturn's rings, the statement said. At that point, the ring system would have thinned out, but some material would still be slowly pulled onto the moon by gravity.

"On a larger, more massive body, this ridge would not be so tall (relative to the body), because gravity would cause it to flatten out," NASA officials said in the statement. "But Pan's gravity is so feeble that the ring material simply settles onto Pan and builds up. Other dynamical forces keep the ridge from growing indefinitely."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter