Photographing a Black Hole: Historic Campaign Now Underway

The campaign to capture the first-ever image of a black hole has begun.

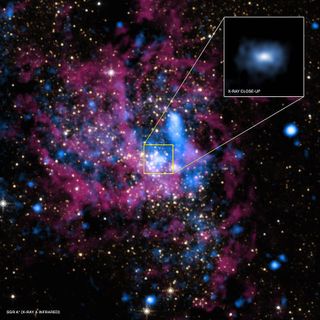

From today (April 5) through April 14, astronomers will use a system of radio telescopes around the world to peer at the gigantic black hole at the center of the Milky Way, a behemoth called Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) that's 4 million times more massive than the sun.

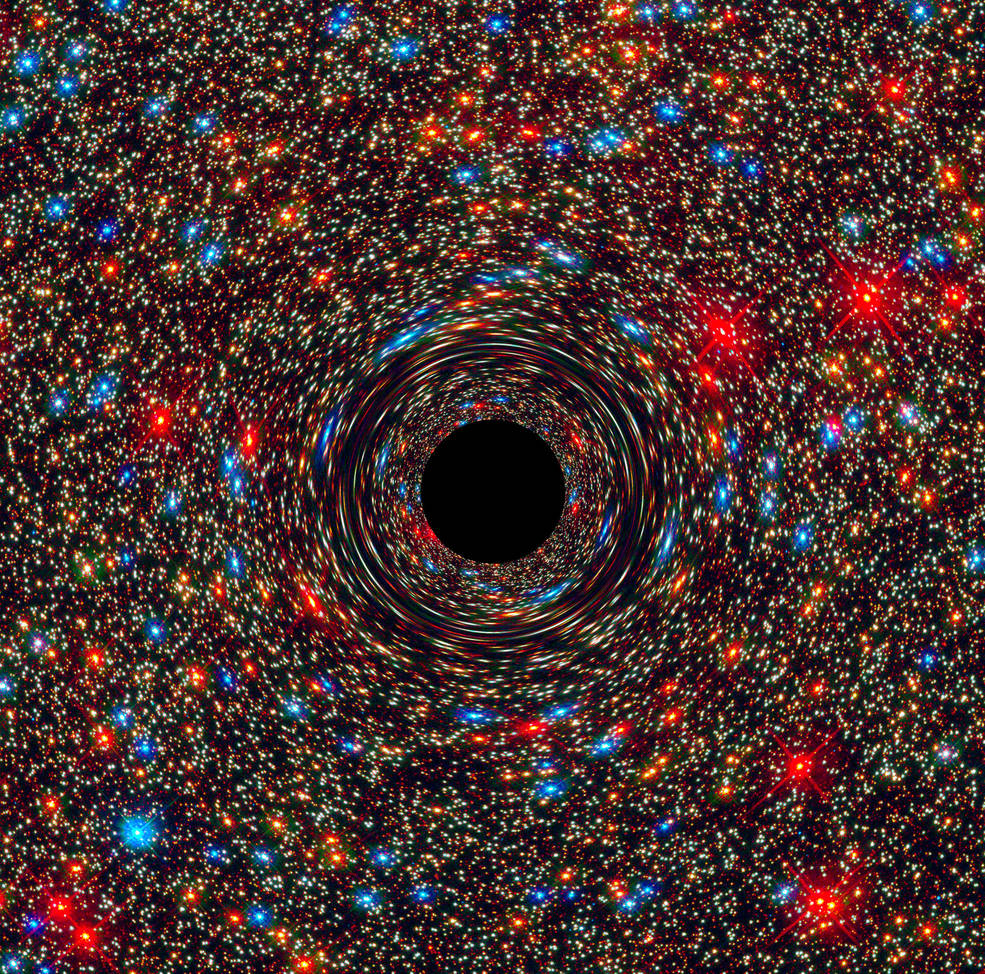

The researchers hope to photograph Sgr A*'s event horizon — the "point of no return" beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape. (The interior of a black hole can never be imaged, because light cannot make it out.) [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

"These are the observations that will help us to sort through all the wild theories about black holes — and there are many wild theories," Gopal Narayanan, an astronomy research professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, said in a statement. "With data from this project, we will understand things about black holes that we have never understood before."

The project, known as the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), links up observatories in Hawaii, Arizona, California, Mexico, Chile, Spain and Antarctica to create the equivalent of a radio instrument the size of the entire Earth. Such a powerful tool is necessary to view the event horizon of Sgr A*, which lies 26,000 light-years from our planet, EHT team members said.

"That's like trying to image a grapefruit on the surface of the moon," Narayanan said.

During the current campaign, EHT is also eyeing the supermassive black hole at the core of the galaxy M87, which lies 53.5 million light-years from Earth. This monster black hole's mass is about 6 billion times that of the sun, so its event horizon is larger than that of Sgr A*, Narayanan said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These observations should help astronomers determine the mass, spin and other characteristics of supermassive black holes with better precision, team members said. The researchers also aim to learn more about how material accretes into disks around black holes, and the mechanics of the plasma jets that blast from these light-gobbling giants.

EHT could also reveal more about the "information paradox" — a long-standing puzzle about whether information about the material gobbled up by black holes can be destroyed — and other deep cosmological mysteries, team members said.

"At the very heart of Einstein's general theory of relativity, there is a notion that quantum mechanics and general relativity can be melded, that there is a grand, unified theory of fundamental concepts," Narayanan said. "The place to study that is at the event horizon of a black hole."

Though the current observing campaign will be over soon, it will take a while for astronomers to piece together the images. For starters, so much information will be collected by the participating telescopes around the world that it will be physically flown, rather than transmitted, to the central processing facility at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Haystack Observatory.

Then, the data will have to be calibrated to account for different weather, atmospheric and other conditions at the various sites. The first results from the campaign will likely be published next year, EHT team members said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.