Researchers Probe Origin of Superpowerful Radio Blasts from Space

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

New work probes the extraterrestrial source of incredibly powerful explosions of radio waves, investigating why that spot is the only known location to repeatedly burst with these blasts.

These repeating bursts may come from a dense stellar core called a neutron star near an extraordinarily powerful magnetic field, such as one near a massive black hole, the study finds.

Fast radio bursts, or FRBs, are intense pulses of radio waves lasting just milliseconds that can give off more energy in a fraction of a second than the sun does in hours, days or weeks. FRBs were discovered only in 2007, and while researchers have detected 20 or so FRBs in the past decade, they estimate that such flashes might occur as many as 10,000 times a day across the entire sky, researchers wrote in the study. [Inside a Neutron Star (Infographic)]

Much remains a mystery about the origins of FRBs, because their brief nature makes it difficult to pinpoint where they come from. Among the possibilities that prior work suggested are cataclysmic events such as the evaporation of black holes and collisions between neutron stars.

However, in 2016, scientists discovered that a fast radio burst known as FRB 121102 could release multiple bursts. "It is the only known repeating fast radio burst source," study co-lead author Jason Hessels, an astrophysicist at the University of Amsterdam, told Space.com.

That FRB 121102 can explode over and over again suggests it does not come from some one-time cataclysmic event, Hessels said. "A key question in the field is whether this repeating fast radio burst source is fundamentally different compared to all the other apparently nonrepeating sources," he said.

To learn more about this FRB, scientists used the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico and the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia to analyze data on 16 bursts from object. FRB 121102 is located in a star-forming region of a dwarf galaxy found about 3 billion light-years from Earth, Hessels said. Because astronomers can see it from such a great distance, the amount of energy in a single millisecond of each of these bursts must be about as much as the sun releases in an entire day, Hessels and his colleagues said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In studying these emissions, the researchers focused on a feature of radio waves known as polarization. This property occurs because all light waves, including radio waves, can ripple up and down, left and right, or at any angle in between. The radio waves from FRB 121102 were short in duration and strongly polarized (with most of the radio waves all rippling in the same direction), similar to radio emissions from young energetic neutron stars previously seen in the Milky Way galaxy, Andrew Seymour, co-author on the study and a researcher at the National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center at Arecibo Observatory, said in the statement.

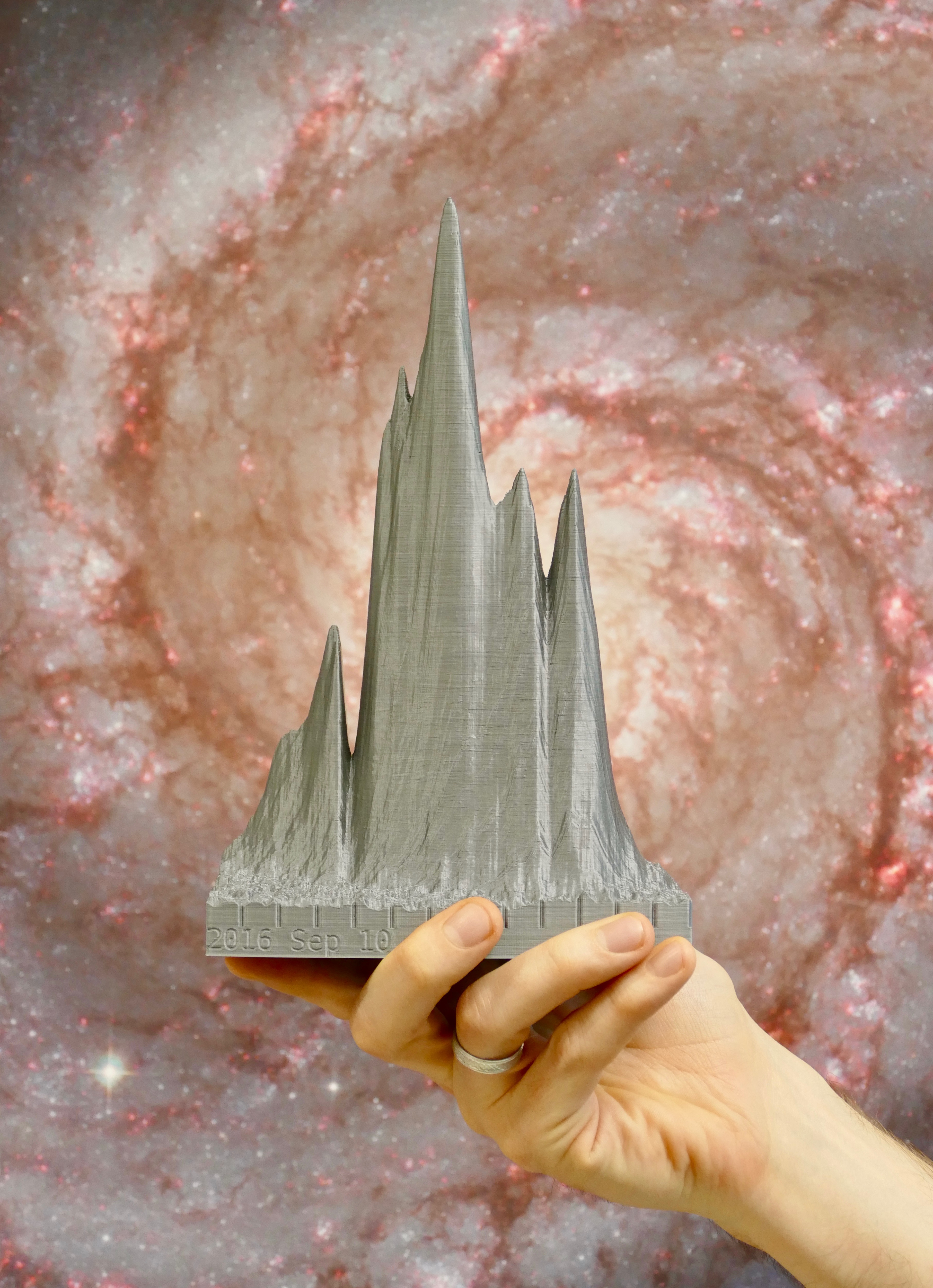

When radio waves pass through a magnetized plasma, or cloud of electrically charged particles, the direction in which they are polarized can twist, an effect known as Faraday rotation. Hessels and his colleagues found that FRB 121102's radio bursts were more than 500 times more twisted than those from any other FRB to date. Gorgeous New Hubble Photo Reveals 'Beating Heart' of Crab Nebula

"I couldn't believe my eyes when I first saw the data. Such extreme Faraday rotation is extremely rare," Hessels said in the statement.

This extreme twisting suggests that FRB 121102's bursts passed through an extraordinarily hot plasma with an extremely strong magnetic field. Such plasmas might exist near either a black hole more than 10,000 times the mass of the sun or the remnant of a supernova, the researchers said.

"Myself and many others would love to know whether this fast radio burst phenomenon has a single or multiple physical origins," Hessels said. "There is a whole host of telescopes coming online in the next few years that promise to discover many more such sources and to answer these questions."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Jan. 11 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us